Keep the Government Out of the News Business

I’ve been thinking of IF Stone while reading the growing stack of reports and essays giving recommendations on how to save the declining news business The outrageous solution increasingly favored by the journalism establishment is one that Stone would have hated -- turning to Washington for help I’ve been thinking of I .

As news organizations shed decent salaries, reasonable working conditions and job security, the business is heading toward a day when it will attract only inquisitive, rebellious misfits. From this group will emerge a few who are talented, tough and driven enough to become the I.F. Stones of the 21st century.

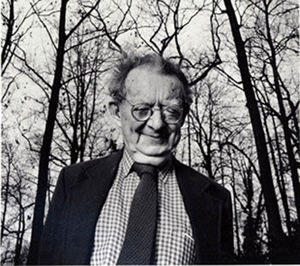

Izzy Stone was a muckraking liberal anti-Cold War journalist who couldn’t get a job during the McCarthy era and went out on his own with the one-man I.F. Stone’s Weekly. “I made no claim to inside stuff—obviously a radical reporter in those days had few pipelines into the government,” wrote Stone, who died in 1989. “I tried to give information which could be documented so the reader could check it for himself. I tried to dig the truth out of hearings, official transcripts and government documents, and to be as accurate as possible. … In the worst days of the witch hunt and cold war, I felt like a guerilla warrior, swooping down in surprise attack on a stuffy bureaucracy where it least expected independent inquiry.”

By reading many newspapers, he discovered that the 1957 underground nuclear tests had been felt 2,600 miles from the Nevada test site. This indicated that a network of stations far away could detect a nuclear test and police a test ban agreement. It was an important point to supporters of a nuclear test ban treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union. It countered the argument of test ban foes who said tests were undetectable 200 miles away from the test site. Stone said that “by telephoning around,” he found a seismologist in the Coast and Geodetic Survey who confirmed to him that the blast had been felt in Fairbanks, Alaska, 2,600 miles from the test. With that, he had his story.

I’ve been thinking of Stone while reading the growing stack of reports and essays giving recommendations on how to save the declining news business. The outrageous solution increasingly favored by the journalism establishment is one that Stone would have hated — turning to Washington for help. It would place the news business in the hands of the same federal government that has tried to stifle many generations of independent reporters such as I.F. Stone.

Growing acceptance of the idea says much about the mentality of mainstream journalism leaders, an attitude that we and the government are on the same side. This is the mentality that led to the news establishment’s acceptance of the Iraq War.

The latest of such proposals comes from Leonard Downie Jr., former executive editor of The Washington Post, and professor Michael Schudson of Columbia University in a study called “The Reconstruction of American Journalism.”

They want the Internal Revenue Service and Congress to allow news organizations to be designated nonprofit organizations under certain conditions. This would permit them to accept tax-deductible donations and foundation grants under Section 501(c)(3) of the tax code.

At present, the tax exemption is granted to charitable, religious, educational, scientific, sports and anti-animal-cruelty organizations. Downie and Schudson propose adding “news organizations substantially devoted to public affairs reporting.”

Anyone who thinks the fox can be safely admitted to this particular henhouse should read what happened almost 20 years ago to Mother Jones, the excellent liberal investigative magazine.

Mother Jones was founded by the Foundation for National Progress and soon made a name for itself with exposés of the exploding Ford Pinto car and tobacco industry lobbying in Washington. The Internal Revenue Service said the foundation qualified as tax exempt. But in the last days of the Carter administration the IRS began an audit. Then, in 1981, the Reagan administration moved to revoke the tax-exempt status of the foundation on the phony grounds that Mother Jones was a moneymaking publication. It was money-losing, bereft of big advertisers, especially after the Pinto and tobacco exposés.

“We watched the once innocuous audit become increasing repressive under the Reagan administration,” said Deirdre English, then the editor.

After three years in which Mother Jones spent $100,000 for legal fees, the IRS reversed itself. But the case shows how naive—to put it kindly—that Downie, Schudson and others of their ilk are in asking Washington for help. No matter how many of their proposed amendments to the tax code are made, a hostile administration can bend and twist the law to damage or close down any publication, Web site or broadcast station that criticizes it.

Just as dangerous is the Downie-Schudson proposal that the federal government create a national Fund for Local News from fees on telecom, broadcast and Internet service providers. “These funds would be administered in open competition through state Local News Councils,” they said.

Their proposal says the “criteria for grants should be journalistic quality, local relevance, innovation in news reporting and the capacity of the news organization … to carry out the reporting.” That’s not what would happen. Every politician and statehouse fixer would try to shape the councils and the grants. What about a little West Virginia paper that proposes an investigation of the coal industry or a Connecticut Web site that wants to dig into the insurance business? Would they get news council grants?

It’s also important to recall the history of two federal commissions that hand out grants, the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. President Ronald Reagan tried to abolish the National Endowment for the Arts, and it was under heavy pressure from the right throughout the 1980s. The National Endowment for the Humanities was led by two famous right-wingers, William Bennett and Lynne Cheney, and gained a reputation for avoiding controversy and denying grants to anyone from the left.

The idea of government help reflects the airy vision of news executives and their allies in journalism education.

They think government aid would restore the days of well-financed journalism with teams of reporters, supervised by editors, investigating potential scandal and being permitted to take months at a time to do it. Actually, such reporting occurred in only a brief period, from the 1960s through the ’80s, when a few national newspapers, the television networks and the news magazines were dominant. Their near-monopoly status allowed them to finance large investigative reporting staffs and an expensive news-gathering process. I was a reporter and editor in those days, and they were great for the journalists and for society.

But that’s ended. The news business is returning to the low-paid days when I began. Advertisers will have more clout than editors. Insecure bosses of Web sites, broadcast stations and newspapers, fearful of being fired, will tyrannize young reporters, who will be judged by the volume rather than the quality of their work. Reporters will be urged to be nice to advertisers. They will not be allowed the time—or be given the encouragement—to dig into the corruption they might see on their daily rounds. They won’t be permitted to make trouble.

Only a few will be persistent or fortunate enough to have an opportunity to raise hell—and they’ll have to do it on their own for little or no money and for small audiences. I had such an opportunity when I was a young legislative correspondent in the California capital, Sacramento. Phil Kerby, the editor of a small liberal magazine, Frontier, encouraged me to write about the lobbyists and special interests that ran the Capitol. Get the real story, he said. Frontier paid a pittance, and I worked weekends to get the stories. But I began to learn how to be a real reporter.

Kerby was someone to emulate, as was Stone. “I am a wholly independent newspaperman, standing alone, without organizational or party backing, beholden to no one but my good readers,” Stone wrote. He didn’t do it by relying on the tax code or writing proposals for foundations. All he accepted from government was permission to send out the Weekly as second-class mail, a right granted newspapers when the nation was founded.

We hope in the future we’ll see more I.F. Stones, more guerrilla warriors on the Web, in print and on the air. Because of them—and not because of a government handout—great reporting will survive, as it always has.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.