Just Ask the Iraqis

Gen. Petraeus and Ambassador Crocker, to no one's surprise, think the "surge" is working. So what if a majority of Iraqis disagree with them?WASHINGTON — It’s all about us.

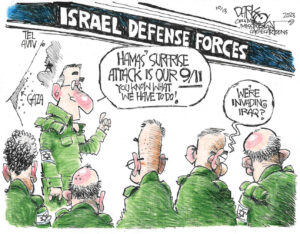

This is why the theatrical masterpiece of Gen. David Petraeus’ testimony to Congress coincided with the anniversary of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. President Bush always has cast the American invasion and occupation of Iraq as part of the larger war on terror, a logical and supposedly unavoidable step to prevent the next 9/11 — or inexplicably, avenge the last. The falsity of the claimed connection was long ago exposed but it resurfaces like an ugly, bloated corpse.

What if the hearings had been held in connection with another anniversary — say, that of the 2006 bombing that shattered the Golden Mosque in Samarra, a spectacular provocation that intensified, possibly beyond hope, the sectarianism that tears at Iraq? “This is as 9/11 in the United States,” Adel Abdul Mahdi, a Shiite politician and one of Iraq’s two vice presidents, said at the time.

Perhaps we would then ask what Iraqis think of the American military “surge,” ostensibly conducted on their behalf. If we did, we would find that they think it is a failure.

Six in 10 Iraqis say security in Iraq overall has worsened since the surge began. That is their grim assessment, according to an extensive national poll conducted jointly by ABC News, the BBC and NHK, a Japanese broadcaster.

The survey cannot be said to contain any data from which even the most facile manipulator could make a colorful collection of upbeat charts. The proportion of Iraqis who rate their local security positively — 43 percent — is unchanged since March. When asked to assess the surge overall, Iraqis are particularly negative: More than two-thirds of them say the stepped-up U.S. military presence has worsened security, worsened the country’s political dialogue, and worsened the pace of reconstruction and economic development.

In Anbar province — held up for the exemplary way in which Americans have suddenly struck tactical security alliances with Sunnis who formerly were our sworn enemies — the outlook is still decidedly glum. Thirty-eight percent of those in Anbar province rated security positively — none had six months ago. Still, nearly half of those in the province identified security as the biggest problem in their lives, and factional fighting in Anbar, the poll analysts said, was reported as being up.

A worsening of attitudes in Baghdad, also a focal point of the surge, is apparent. Sixty-eight percent of Baghdad respondents called local security “very bad,” a proportion that is up since March.

Resentment against Americans is undiminished, and has reached such levels that 57 percent of Iraqis say that violence against U.S. forces is acceptable, up six points from when the survey was last conducted in March. In February 2004, only 17 percent of Iraqis said they condoned violence against the Americans in their midst.

Fear, pessimism and resentment grip the country. Why should it be otherwise? Iraqis do not sense that this war was ever about them. They cannot reconcile their lives of deprivation and destruction with American television reports of administration officials claiming that things are beginning to go much better, thank you. Could there be a more blatant display of indifference to their suffering?

For the implacable Bush administration and for the impatient Congress, a single force drives all discussion about Iraq. It has not much to do with Iraqis. Their concerns are the future of the U.S. military, of U.S. prestige, of U.S. access to oil, of broader U.S. strategic interests in the Middle East. Add to the mix the political imperatives that inspire all of them — Bush’s intent to hand over the messy endgame to the next president; lawmakers’ determination to find a path to re-election that guides them safely through this quagmire — and you have a myopia that is bereft of morality.

Americans always have believed themselves to be exceptional, set apart from the rest of the world in both triumph and sacrifice. The instinct intensified after the 2001 terrorist attacks that have defined our contemporary politics.

It is as though history began, or ended, on that day. The next time that banal question — why do they hate us? — is asked, it would be worth reading this poll of Iraqis, if only to get a glimpse of the answer.

Marie Cocco’s e-mail address is mariecocco(at)washpost.com.

© 2007, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.