Judy Chicago on Making Art Her Way and Remaking the Art World

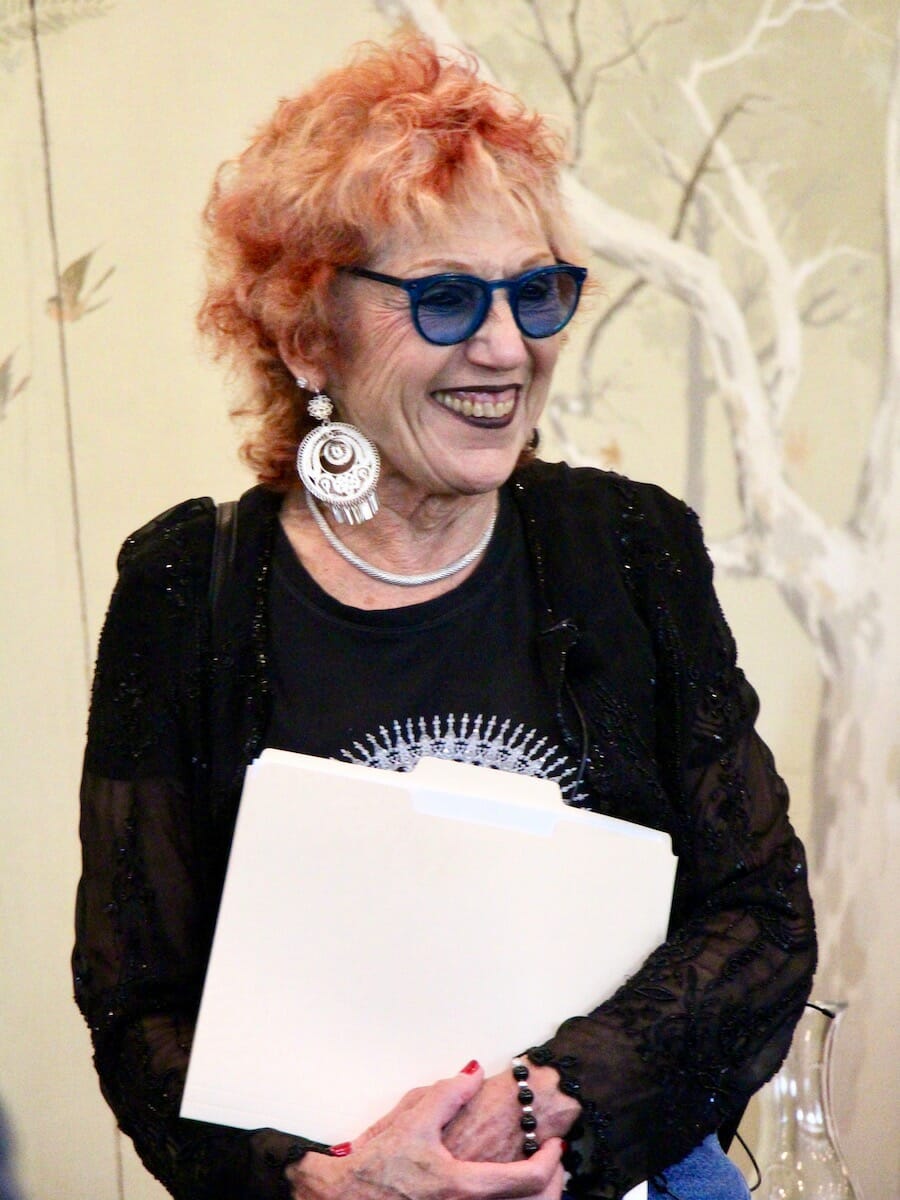

The trailblazing artist tells how she fused feminist sensibilities with production methods in works that were initially written off by male critics and peers—and are now being celebrated in retrospectives and salutes. Judy Chicago. (Jordan Riefe)

Judy Chicago. (Jordan Riefe)

For her landmark 1979 installation, “The Dinner Party,” honoring 39 influential historical and mythical women, artist Judy Chicago added to writer Mary Wollstonecraft’s place setting a crocheted depiction of the proto-feminist author giving birth to her daughter, Mary, whom she died delivering. The image of Wollstonecraft’s final scene became the seed for Chicago’s next collaboration. The end result, “Birth Project,” was woven by 150 female needleworkers and included roughly 84 textile artworks thematically connected to childbearing. Sixteen selections from that joint production are currently on view at the Pasadena Museum of California Art through Oct. 7.

“Most of my projects I start with research. Before I make any images, I educate myself on the subject,” Chicago said of her process in an interview with Truthdig. “I was living in Northern California when I was doing the ‘Birth Project,’ which happened to be, in the early ’80s, the center of the alternative birth movement. It was really easy to see birth videos.”

With titles like “Birth Tear/Tear,” “The Crowning” and “Mother India,” various forms of textile work capture variations on the theme of childbirth. As with “The Dinner Party,” Chicago embarked on a sprawling collaboration, painting or otherwise rendering her images, then distributing them to women around the country to embroider over per her specifications.

Employing needlework as a medium, Chicago sought to elevate craft to art, instilling it with universal meaning. “It depends upon the intention, not upon the medium,” curator Dr. Viki Thompson Wylder explained. “The fact that this is crochet doesn’t make it a craftwork. What would make it a craftwork for [Chicago] is simply to demonstrate skill and not to imbue meaning. And certainly there is meaning here—and thus the medium, crochet, does not affect its designation as art.”

To monitor progress, Chicago would often travel to a spot convenient to a number of needleworkers where she might review their work. For other pieces, she would visit private homes, or some might send her completed portions in the mail. Ironically, her aim to elevate crochet to something other than the product of hobbyists in living rooms relied upon women in living rooms, working on “Birth Project.”

“Mother India,” based on controversial historian Katherine Mayo’s 1927 book of the same name, places a figure of Shiva at the center, though his gender is changed to a very pregnant female. Surrounding her are panels depicting arranged marriage, female infanticide, child marriage, childbirth and subsequent shunning of the mother.

Another panel shows a woman being forced to join her husband on his funeral pyre in the ritual of sati. The four corners each feature images of the Taj Mahal. That might seem a kitschy touch, but instead it turns bitterly ironic considering Mumtaz Mahal, for whom the mausoleum was built, died at the age of 37 while giving birth to her 14th child.

“Mother India” was meant to have a counterpart, “Father Africa,” but issues of cultural appropriation and controversial practices kept Chicago from pursuing the project. “It would have made me have to deal with images of genital mutilation. And for some, whose vaginas have been sewed up, birth is a traumatic and horrifying experience,” Chicago explained. “I’m not going there.”

After her experience with “The Dinner Party,” Chicago was taking no chances with “Birth Project.” The former was greeted coolly by the male-dominated art world but still managed to draw 100,000 visitors in three months during its first show, although critics had the final say and a planned exhibition tour collapsed. But a grassroots-fueled tour took its place, with the installation visiting 16 destinations in six countries on three continents after its initial run in San Francisco.

“Birth Project” toured for 10 years, with portions showing in venues ranging from birthing centers to major museums, after which works were permanently placed in various institutions around the world. In recent years, Chicago reconnected with some of those institutions and was pleased to find enthusiastic and grateful curators who prized the works; a stark contrast to her customary experience as a pioneer feminist artist.

Born in Chicago, the daughter of a Marxist labor organizer and a medical secretary, Judy Cohen was dubbed Judy Chicago when gallerist Rolf Nelson heard her thick Second City accent and nicknamed her. She studied at UCLA in the 1960s at a time when Ferus Gallery was the center of modern art in Los Angeles, and the highest compliment was to be told she painted like a man. Gallerist Walter Hopps once visited the studio space she shared with two male artists in Pasadena and refused to look at her work, later lamely explaining that he was too embarrassed to address her because her work was so much better than that of the others.

Such instances led her to conclude she ought to stop trying to be one of the guys and embrace feminism, not just in thought but in practice. In 1970, she established the first feminist art program, at California State University, Fresno, where female artists had a space of their own. Two years later, she established Womanspace with artist Miriam Schapiro, the first gallery dedicated to exhibiting female artists.

Following the success of “The Dinner Party” and “Birth Project,” Chicago embarked on “Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light,” a mixed-media series using painting, stained glass, photography and tapestries that explores the horror of the final solution and the inspiration of survivors. For that series, Chicago was informed by filmmaker Claude Lanzmann’s epic documentary on the subject, “Shoah.” “I came out of Holocaust Project $55,000 in debt on credit cards, no verifiable income,” she said, smiling and slowly shaking her head. But she got a husband in the process: her photographer, Donald Woodman. “At age 60, I had my first mortgage, which we just paid off,” she said.

Financial worries are long past as the 79-year-old artist prepares for her first major career retrospective, “Judy Chicago: A Reckoning,” at Miami ICA in December, timed to coincide with Art Basel. At Villa Arson in Nice, France, she has a mini-retrospective through Nov. 4 that includes paintings, sculptures and installations. Early next year, La Scala will publish a major monograph of her work.

“The End,” a new series of 37 paintings on black glass and porcelain, along with two bronze reliefs, goes on display in June at Washington, D.C.’s National Museum of Women in the Arts, followed by a museum-size show of early works in September 2019 at Jeffrey Deitch’s new space in Hollywood.

“I’m a student of history, and ‘The Dinner Party’ taught me about the long history of pushing forward and pushing backwards. I was fortunate to live through the thrill of pushing forward, and now I’m living through the nightmare of pushing backwards,” she sighs, citing the current level of misogyny in the national discourse.

But there’s hope in the fact that a figure like herself, whose work was derided as “very bad art” by New York Times critic Hilton Kramer, is now being celebrated. “I destroyed a lot of my early work,” she says. “People didn’t even know about some of my installations and early work. It’s all being brought back. It’s fantastic.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.