John Lukacs on Nicholson Baker’s ‘Human Smoke’

Was World War II necessary? In an exercise in literary hygiene, a distinguished historian casts a skeptical eye at an acclaimed novelist's revisionist take on the "Good War."

This book is bad. To review a bad book is more difficult — more precisely: more wearisome — than to review a good book. A bad book is bad for many more reasons — more precisely: in many more instances and ways — than how and why another book is good. There is a deeper reason for this difficulty. This is that in our perception of every human act the why? is already implicit in the how? Our dislike of any expression by a human being, including a book, instantly rises out of the why. Why did this person do, or write, or say this? Yet this normal reaction must be controlled, or tempered, by Samuel Johnson’s plain and wise and classic admonition: “Intentions must be gathered from acts.”

So, in this case of Nicholson Baker’s “Human Smoke,” I must try my best to separate my discussion of the how from the why. That is: the written evidence from an imputation of its author’s motives.

“Human Smoke” pretends to be a history of the origins of the Second World War. To begin with, its time frame and, consequently, its proportions are senseless. Its first item, on its first page, relates something from August 1892. There follow three pages, Baker-lite items, about the First World War; then 27 pages until Hitler’s assumption of power; then another 99 pages, 1933 to September 1939, about the origins of the Second World War — which is Baker’s main subject. So he declared in the subtitle of his book: “The Beginning of World War II, the End of Civilization.” Yet after “the End of Civilization” come 336 pages about the history of the war, ending with the curious date of Dec. 31, 1941, more than three weeks after Pearl Harbor. How (and why) was Dec. 31, 1941, the End of Civilization?

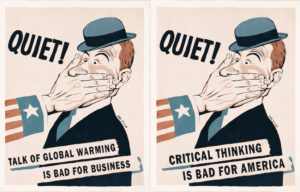

And now to the main how question. What do all of these pages contain? Most of them are clippings from newspapers. I quote Baker from his afterword: “The New York Times is probably the single richest resource for the history and prehistory of the war years. …” George Orwell once wrote that nothing is very accurately printed in a newspaper: a reasonable maxim by a deeply honest Englishman. What would Orwell think of Nicholson Baker? Baker’s villains are Hitler, and Churchill, and Roosevelt. Orwell admired Churchill. Really, there is no arguable equivalence here.

Some of Baker’s newspaper clippings are interspersed with clippings from published books. They are sequential in time, but many of them make little sense. Some of them, and Baker’s presentations of many of them, are full of inaccuracies and errors. To list them would fill something like a 10,000-word review. Yes, it is more difficult to review a bad book than a good one. Besides — or not so besides — many of these items are badly written. In many instances Baker presents them with his comments, and then ends them with a repeated thumping of a muffled gong: “It was June 17, 1940”; or “It was January 2, 1941.” Sometimes his very dates are wrong. Worse than that: Perhaps one way to review this book is to write a parody of Baker’s method and style. Here is one — very random — sample:

On Page 334, Nicholson Baker writes: “The United States sent its first Lend-Lease boatload of food to England. Lord Woolton, minister of food, was waiting for it on the dock. ‘Cheese!’ he said. He ate some Wisconsin cheddar from an opened crate. ‘And very good cheese, too,’ he added.

“There were four million eggs on the boat, as well, and nine thousand tons of flour. It was May 31, 1941.”

John Lukacs writes:

“Nicholson Baker’s book was published by Simon & Schuster. The New York Times printed a long interview with this celebrated writer, written by Charles McGrath, who visited him in his home. Nicholson Baker ate a grilled cheese sandwich. It was February 29, 2008.”

On Page 35 there is a snippet of an American’s interview with Ernst Hanfstaengl, then Hitler’s social secretary, on April 1, 1933: “Hanfstaengel [his name is misspelled] sipped his wine. He was an ardent booster for Aryanism, but he was a dark-haired man, not particularly Nordic-looking — except that, as he had been heard to say, his underarm hair was blond.” Whence “The Beginnings of World War II, and the End of Civilization”?

I have just finished writing a small book about one of Churchill’s speeches (on May 13, 1940, his “Blood, Toil, Tears and Sweat” speech) and about its then reception. There are six and a half lines about that speech in Baker’s book, with three major mistakes about its reception.

In his afterword, on Page 474: “The title [of this book] comes from Franz Halder, one of Hitler’s restive but compliant generals. General Halder told an interrogator that when he was imprisoned in Auschwitz late in the war, he saw flakes of smoke blow into his cell. Human smoke, he called it.” Halder was never in Auschwitz, imprisoned or not.

But, now, about the why. Why did Baker write this badly jumbled, half-baked book? Now I must say something in his favor. He is a pacifist. But pacifist, too, is an often inaccurate word. He writes, and thinks, that the Second World War was not A Good War, that it was a disaster, that indeed it was the End of Civilization. I have often quoted the old Irish biddy whom her neighbors had asked if the gossip about the young widow at the end of the street was true. And she said: “It is not true; but it is true enough.” I have also said that historians ought to face the opposite problem: that this or that may be true; but also not true enough.

That war is awful is true. It is also true that Churchill and Roosevelt wanted — more: they chose — war to destroy Hitler. Especially Churchill thought that Hitler’s winning the war — more precisely: his ruling all of Europe — would mean something like the end of Western civilization. He was not very wrong.

It is true that Hitler did not want to conquer the British Empire. It is true that he did not want — he couldn’t — to invade the United States and the Western Hemisphere. What he wanted (and he said this often) was for Britain and the United States to accept his domination of Europe, including his conquest of most of Central and Eastern Europe. But what did that mean? After conquering Poland, he would have gone into Soviet Russia, defeated it, establishing German, and National Socialist, rule over most of Eurasia. And what would have happened then? Not only to the strategic interests but to the British and American peoples’ state of mind?

It is true that in 1940 Churchill chose to fight Hitler’s Germany with every possible means at his disposal (and those few and ineffective bombing raids were the only means at his disposal then). It is also true that Roosevelt wanted to get into the war against Hitler — if necessary, through the back door of inducing Japan to attack America. But, beneath and beyond all of this: Hitler had to be resisted. Resistance, truly, is a conservative word. It also means: if necessary, fighting.

A fair amount of Baker’s snippets deal with the Germans’ humiliation and persecution and eventual murdering of Jews. I do not for a moment think — this belongs to the why question — that Baker did this to cover himself. His concern with what happened to the Jews of Europe seems authentic and honest. Now: It is true that Jews hoped for Churchill and Roosevelt to go to war against Hitler. But in 1939 and 1940, Churchill and Roosevelt decided to fight Hitler not because of the Jews. It is true that until about August-September 1941, the policy of the Germans was to force the Jews to emigrate: It was expulsion, not yet mass extermination. But thereafter this was no longer possible. It is also true that this final decision to proceed to extermination occurred only after — and, in some ways, perhaps even because of — the full coming of the war between the United States and Germany. But Baker never asks the questions: How much have Jews contributed to the British and American decision to war against Germany? And: Had Churchill and Roosevelt not gone to war, what would have happened to the millions of European and Russian Jews? The Jews did not cause the war; and the war did not go on because of the Jews. True, millions of Jews perished because of the war; but it was a war Hitler started, wishing that he would not have to fight Britain and the United States.

He did and he lost. And Western civilization survived — even with a portion of Europe falling under Soviet domination for a while. Millions died in the war; other millions survived. What now matters, in the long run, is what we know of that war. We live forward; but we can only think backward, Kierkegaard once said. Knowledge, all knowledge, depends on memory; and history is the memory of mankind. All kinds of comfortable, and uncomfortable, truths — and half-truths — are latent within history, potential arguments for all kind of purposes; but they are seldom enough. What happened and what could have happened are not separable in our memories, in our minds. And why and how are not separable either.

John Lukacs is the author of more than 20 books on topics in European history, including “Five Days in London: May 1940,” “The Hitler of History,” and “The Last European War.” Currently professor of history emeritus at Chestnut Hill College, he has also taught at Columbia University, the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Budapest. His new book, “Blood, Toil, Tears and Sweat: The Dire Warning — Churchill’s First Speech as Prime Minister,” will be published by Basic Books in May.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.