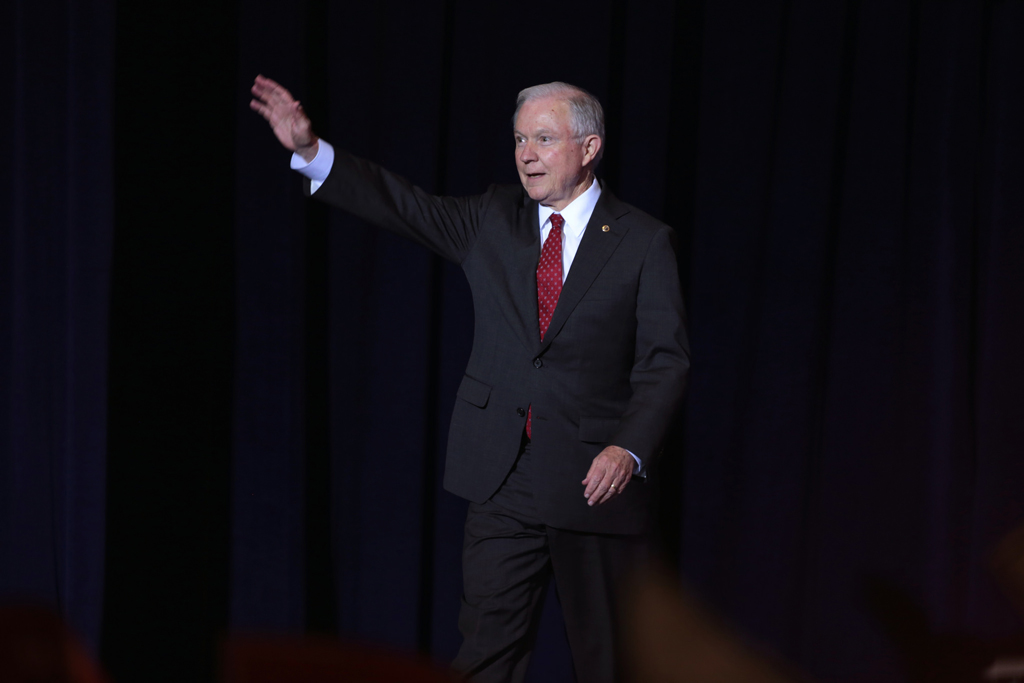

Jeff Sessions Is Bringing Back Civil Forfeiture With a Bang

The police can take your assets even if you haven't been convicted of a crime. Gage Skidmore / CC BY-SA 2.0

Gage Skidmore / CC BY-SA 2.0

This piece originally appeared on Moyers and Company.

In mid-July Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced a policy rollback that’s getting criticism from both sides of the aisle, and the center, too. As The Washington Post notes undoing this Obama-administration policy is a big deal — and means big money.

Known as “adoptive forfeiture,” the program — which gives police departments greater leeway to seize property of those suspected of a crime, even if they’re never charged with or convicted of one — was a significant source of revenue for local law enforcement. In the 12 months before Attorney General Eric Holder shut down the program in 2015, state and local authorities took in $65 million that they shared with federal agencies, according to an analysis of federal data by the Institute for Justice, a public interest law firm that represents forfeiture defendants.

President Trump even mentioned the process in a now somewhat infamous exchange with Texas law enforcement officials when he vowed to “destroy” a state lawmaker that stood in the way of asset seizures.

Civil asset forfeiture has become increasingly controversial, especially because of the extremely limited chance to appeal the proceedings. And then there’s the fact that you don’t have to be convicted of a crime to be subject to civil forfeiture — it’s the property that is at issue. The Institute for Justice found in a 2015 report that between 1997 and 2013, 87 percent of the Department of Justice’s forfeitures did not require any criminal charge or conviction.

Jeff Sessions has a vehement defense of the program:

Civil asset forfeiture is a key tool that helps law enforcement defund organized crime, take back ill-gotten gains, and prevent new crimes from being committed, and it weakens the criminals and the cartels. Even more importantly, it helps return property to the victims of crime. Civil asset forfeiture takes the material support of the criminals and instead makes it the material support of law enforcement, funding priorities like new vehicles, bulletproof vests, opioid overdose reversal kits and better training. In departments across this country, funds that were once used to take lives are now being used to save lives.

BillMoyers.com wanted to find out more about the blurry world of civil forfeiture so we talked with Sarah Stillman, a New Yorker writer and director of the Global Migration Program at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, and the author of “Can the President ‘Destroy’ Criminal-Justice Reformers?” — the result of a yearlong investigation into the controversial process.

Stillman told us that Sessions statement is misleading:

What stood out to me when Sessions made his comments is that one of the things he underscored is that he sees it as totally reasonable in that we’re going after bad guys. He went on to say you can tell that because four out of five people don’t challenge the forfeiture. Of course, he doesn’t mention that it costs money to do that and that is also a big causal factor as to why people don’t challenge it.

In fact, people who have been subject to civil forfeiture are not entitled to a lawyer. Many times, paying a lawyer would cost more than the property may be worth. And, there are only a handful of pro bono law clinics, like The Institute for Justice, that are taking on these cases.

In part Stillman says getting rid of civil forfeiture is just plain common sense among the American populace. A survey by the HuffPost and YouGov found that 71 percent of those surveyed hadn’t even heard of the term. A meagre seven percent supported the practice.

Indeed, Stillman says:

There’s a really easy solution to that which is just make all forfeiture criminal. That to me is the intuitive part of this. The idea that if you commit a crime, and you’re profiting off of that crime, and you’re proven to have done so, then the goods that you’ve got can be taken away from you. I think most citizens would get that concept and be able to stand behind it. I think what people don’t comprehend is the distinction between criminal forfeiture, the process I just described, and civil forfeiture where nothing really has to be proven against you.

Sessions is bucking a nationwide trend by putting so much emphasis on civil forfeiture. According to Stillman: “One of the things that really stands out to me about forfeiture is that it’s so rare to have a bipartisan issue where you’ve got so many voices on the right and so many voices on the left both saying the same thing.” Some conservative think tanks like Cato and the American Enterprise Institute are against the practice.

Stillman notes that the practice of civil forfeiture varies widely by both state and locality. Due in part to the curtailing of municipal and local police budgets, forces have come to rely on it as a way to add to dwindling coffers. Yet, over 20 states have recently passed laws that limit civil forfeiture. (Read the Institute for Justice’s report: “Policing for Profit” for a current list.) Many of those reforms are to change the way the monies are disbursed — so that the flow of money doesn’t come directly back into the department’s pocket.

Sessions is in favor of “equitable sharing,” which Stillman says just lets state and local law enforcement agencies use a loophole by first turning money over to the feds who then give it right back. But, she says, there is a layer of hope in that most of the decisions about criminal justice matters are made at the state and local level — and the tide doesn’t seem to be turning back in Sessions’ direction.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.