Jacob Heilbrunn on Alger Hiss

Susan Jacoby’s lucid new book reminds us that the Hiss case offered a vengeful postwar right a golden opportunity to tar the New Deal as a crypto-communist conspiracy -- and why it still matters.

In 1984 Ronald Reagan returned to his alma mater, Eureka College, where he had been a middling student who devoted himself to extracurricular activities such as the drama club rather than his studies. Now, the former B-movie star and pitchman for General Electric was returning in his latest role — as a popular, if unlikely, American president. He gave the students a dose of conservative political philosophy. He didn’t cite Barry Goldwater or economist Friedrich Hayek as his great heroes. Instead, Reagan focused on someone else, the former communist turned renegade, Whittaker Chambers, who created an uproar in the late 1940s by stating that his old friend, Alger Hiss, a State Department official and member of the Eastern establishment, was, in fact, a Soviet spy. Chambers, Reagan said, was a monumental figure in American history. He had single-handedly created a “counterrevolution of the intellectuals” by breaking with the communist movement. Chambers’ massive autobiography, “Witness,” had cured Reagan of a dangerous delusion that afflicted so many of his coevals. As Reagan put it, “For most of my adult life, the intelligentsia has been entranced and enamored with the idea of state power, the notion that enough centralized authority concentrated in the hands of the right-minded people can reform mankind and usher in a brave new world.”

Ever since he pulled microfilm of State Department documents from a hollowed-out pumpkin on his farm, Chambers has been a totemic figure for the modern conservative movement. In July 2001, I myself attended an event in the Old Executive Office Building held by the Bush White House to commemorate the 40th anniversary of Chambers’ death. As journalist Robert Novak spoke, I watched slack-jawed. It was as though time had been suspended for a moment and the McCarthy era had returned, as Novak lauded Richard M. Nixon and raged against the traitorous liberals who had sneered at Chambers for having the courage to expose a communist conspiracy at the heart of American government. Conservatives, Novak said, would be eternally grateful to Nixon for backing Chambers.

Indeed, for Reagan, William F. Buckley Jr. and other traditional conservatives, Chambers was a heroic prophet who alone had the moxie to endure the obloquy of the liberal-left in the service of truth. Obsessed with the notion that Yalta, where Hiss had been a minor figure, was a sell-out to the Soviets, a betrayal of Eastern Europe to Josef Stalin by a befuddled Franklin D. Roosevelt, conservatives flayed Hiss and other New Dealers as nefarious figures who had been working hand in glove with the KGB. And for generations of neoconservatives, Chambers’ searing experience in breaking ranks was one that they themselves tried to recapitulate, positioning themselves as former leftists who had seen the light and spurned the totalitarian American intelligentsia, no matter the cost to their careers, which somehow seemed to prosper, not despite but because of their supposed apostasy.

In “Alger Hiss and the Battle for History,” Susan Jacoby explores the anfractuosities of the Hiss-Chambers affair. Jacoby, a gifted writer who is the author of numerous books, including “The Age of American Unreason,” reports that her 86-year-old mother responded to the news that she was working on public perceptions of Hiss and Chambers by asking, “Who cares about that anymore?” It’s a fair question. The two men formed a sort of ideological fault line in American intellectual life for decades. On one side were the uncouth conservatives who lauded Chambers; on the other, the anxious liberals who sought to defend Hiss, or at least mitigate his espionage sins. Jacoby seeks to show that the dispute over the two men isn’t a musty affair from the past. Instead, it offers a revealing glimpse into American political history, whether it’s the Cold War or the war on terrorism. Her assessments of the positions of the two camps will probably meet with the approbation of neither, but she lucidly and expertly maps out the terrain upon which the Hiss-Chambers engagements have been fought over the decades.

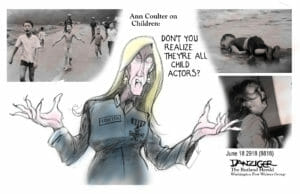

As Jacoby reminds us—and it is a reminder that cannot come too often—the Hiss case offered for a vengeful postwar right a golden opportunity to tar the New Deal itself as a crypto-communist conspiracy. The stakes were never about Hiss himself, whose influence on Roosevelt was nugatory. Rather, he became a symbol for the iniquities of the New Deal, for the quislings such as Dean Acheson who had sold out America to the Reds. This exercise in historical revisionism allowed the right to efface its own history of having embraced isolationism during the 1930s and, sometimes, worse, having adulated Nazism and scorned the British Empire as trying to inveigle the U.S. into combat on the European continent, all of which is beautifully spelled out in Philip Roth’s indispensable “The Plot Against America.” As the Chicago Tribune, formerly the tribune of the isolationists and inveterate foe of FDR, proclaimed, “So we find this traitor hobnobbing through the years with the mightiest of the New Deal mighty. He advises the President. He is the favored protégé of two men who are kingmakers within the burocracy.” (The Tribune favored phonetic transliteration of some words.) Hiss served as the opening act to Sen. Joseph McCarthy, who went after Acheson and his peers with a vengeance. And not only McCarthy. It was Richard Nixon who had urged Chambers on, and who, as Dwight Eisenhower’s vice presidential nominee, would denounce Acheson as leading a “cowardly College of Communist Containment.” Jacoby, then, has it right when she remarks that the Red-hunters not only claimed that treachery had helped turn the Soviet Union into a global power but that the “logical extension of that claim was a blurring of the distinction between communism and liberalism, since many of the most influential anti-Communist liberals, such as George Kennan and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., were not only willing to credit the Soviets for their role in defeating Hitler but felt that containment and coexistence … must form the basis for an American foreign policy that would eventually thwart Soviet ambitions.” Jacoby also astutely notes that the right has doggedly continued to tar liberalism as tantamount to socialism, even Bolshevism. In 1994 Newt Gingrich said that Democrats should be depicted as backers of “Stalinist” policies and political values. According to Jacoby, “That Joseph Stalin had been dead for more than forty years, and that the Soviet Union itself had ceased to exist, did not dissuade the Republican right from its conviction that Stalinism and communism could still be hot-button issues for the American electorate.” Indeed, the egregious Ann Coulter extruded an entire volume attempting to make the case that McCarthy had it right and that liberals remain traitors down to this very day.

If Jacoby is hard on the right, she is also very critical of what she sees as “the passion that a handful of liberal intellectuals have invested in keeping open the tiny possibility that Hiss really was thoroughly innocent and was framed by the FBI.” Jacoby traces these passions back to the 1930s when the Nazi peril prompted a number of American intellectuals to join the Communist Party, or at least become fellow travelers. She notes that the “view of leftists as nothing more than dupes or dopes and of active Party members as the incarnation of evil does not take into account the psychological and political effects of the long impotence of the democracies in confronting Nazi aggression as the thirties wore on.” Of course, the brutal wake-up call came with the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact in 1939, which divided up Europe between the two great dictators, Stalin and Hitler. It was no longer possible to hit the snooze button on what was transpiring in the Soviet Union.

For his part, Chambers had already abandoned the party, going underground for fear that he would be assassinated by Stalin’s agents, which was not an exaggerated fear. Hiss had evidently not. As Jacoby underscores, the evidence that Hiss was innocent of serving as a Soviet spy is sparse. It requires contortions to suggest that he was not and to explain away the evidence suggesting that he was. Again and again, Hiss would resort to legalisms and qualifiers to try to wriggle out of culpability for espionage. Ultimately, he was found guilty of perjury and sentenced to jail. But Hiss had found a new crusade—himself. He spent decades trying to restore, or at least rescue, his reputation, which, he alleged, had been traduced by a conservative cabal led by Nixon. It never quite took.

Part of the problem, Jacoby indicates, was that Hiss himself was something of a bore. His first attempt at self-rehabilitation came in his 1957 book, “In the Court of Public Opinion.” Not having perused it, I am entirely willing to take Jacoby’s word that it is “arguably the dullest book ever written about the Hiss case. It is devoid of political or social analysis, not to mention emotion.” By 1960, Hiss had pretty much fallen off the political map. Jacoby reports that Hiss, who was working for a barrette company named Feathercombs, was occasionally confused with the Nazi Rudolf Hess (who was languishing in Berlin’s Spandau prison). Jacoby believes that by the 1970s, Hiss began to enjoy partial exoneration, at least in the eyes of the academic left, which had witnessed Vietnam and Watergate and concluded that Hiss himself was an early victim of a government run amok. But she also devotes much attention to the publication, in 1978, of Allen Weinstein’s “Perjury,” which dealt a body blow to Hiss’ attempts to recoup his reputation. Jacoby concludes by observing that the tragedy of the Hiss case is that it wasn’t conducted more cleanly. Had the troglodytic House Committee on Un-American Activities not existed, she says, “many on the left might have been more open to the possibility, at an earlier period of history, that Hiss really was guilty and that, whatever the motive, it is a bad idea to have people in sensitive government jobs passing on confidential information to any foreign government.”

The strangest part of the Hiss case, however, remains his refusal, or inability, to accept responsibility for his actions. It’s a pity that Jacoby doesn’t cite Murray Kempton’s brilliantly insightful essay on Chambers and Hiss titled “The Sheltered Life,” in his collection “Part of Our Time,” edited by David Remnick. In it, Kempton offers the most persuasive explanation for Hiss’ lifelong defiance. Pointing to Hiss’ striving to enter the gilded world of the high-class WASPs, he writes: “we are all what our background makes us and … the world of shabby gentility teaches the best of its sons that, when all else goes, empty though it is, they must fight to the death against losing the precious little they have won.” Whether Hiss succeeded in protecting his small hoard, however, is dubious. Despite Jacoby’s portentous title, it seems more likely that the battle over Hiss has devolved into minor spats that retain little, if any, of the emotional power they once possessed. Hiss has disappeared as a force on the left. The lingering political influence of Chambers upon the right, however, is another matter entirely.

|

Jacob Heilbrunn, a former editorial writer for the Los Angeles Times, is the author of “They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons.” |

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.