It Takes Power to Control Power

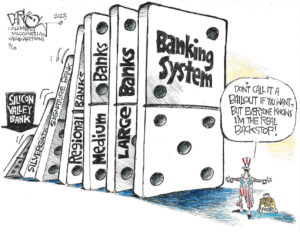

Discredited as the financial powers are, their wealth alone continues to provide them with wildly disproportionate influence over the political process.With a furious majority of American voters demanding security from the depredations of Big Capital, all of the filibustering and bargaining in Congress will inevitably produce a bill described as “financial reform.” Partisan sniping aside, neither Democrats nor Republicans so far have proposed a deep and thorough cleansing.

Republicans like to pretend that they had nothing to do with the enormous bank and insurance bailouts of 2008, forgetting that most of them voted to support the “troubled asset” program, and that the authors of the program were officials of the George W. Bush administration.

Rather than merely disowning those actions, the best course is to ensure that we avoid future subsidies to the undeserving rich. That means more regulation and smarter regulation, not less — and a direct repudiation of arguments advanced by politicians of both parties in the not-so-distant past.

Today’s ideological divide is between Republicans who encourage anti-government fervor and market worship, and Democrats who insist that government can and must balance corporate power by acting when markets fail. No honest observer can still believe — as many once did — that the unbound self-interest of financiers will correct excesses and direct capital to the benefit of the broader economy automatically. No less a libertarian ideologue than Alan Greenspan, the economic “maestro” who drew his inspiration from the writings of Ayn Rand, admitted almost a decade ago that such blind faith was naive and dangerous.

So it is important to cut through the fog of militant ignorance represented by the tea party movement. If the public actually wants to stop bailing out rich brats who make stupid and destructive bets in the Wall Street casino, government must be empowered to oversee derivative trading. And if the public wants a national economy that provides decent jobs and useful goods — rather than super-profits for financial firms — then government should encourage production and construction while sharply regulating speculation.

Skepticism about the motives and wisdom of the bankers is essential if we are to avoid suffering from their inevitable mistakes and crimes. Until the onset of the crisis, in 2008, the broad political assumption was that the reigning financiers were too smart and too knowledgeable to be questioned, let alone arraigned.

Even in the wake of Enron, those “masters of the universe” were permitted to pursue whatever deals and schemes they wished, without accountability or transparency, because they told us that public interference would ruin the prosperity they had brought us. At great cost, we have learned otherwise — or should have. The full indictment is yet to be handed up, but its particulars will range from irresponsible misdemeanors and small-time scams to unprecedented billion-dollar larcenies.

Discredited as the financial powers are, their wealth alone continues to provide them with wildly disproportionate influence over the political process. Given the complexity of the modern global economy — and the issues of derivative trading, consumer protection and the winding down of too-big failures — it will be difficult for voters to judge what qualifies as true reform. Fortunately, there are experts with years of experience in the markets who seek to promote the public interest instead of gaming the system.

Among their basic recommendations are simplification and transparency in the financial markets, decreased leveraging, expanded regulation, permanently restrained interest rates and an independent consumer protection agency. At the very least, say independent experts such as Robert A. Johnson, the former chief economist of the Senate Banking Committee, we must prohibit institutions protected by federal deposit insurance from undertaking deals that involve huge risks.

Moreover, we must end “too big to fail” by ensuring that government has the power and resources to dismantle such firms — without disastrous disruption and without enriching those who gamble blindly, expecting taxpayers to reimburse their losses.

Democrats sound more serious than Republicans in confronting these existential challenges to the economy, but will they go far enough? Unless they can pass the necessary minimum reforms, we may someday find ourselves facing a worse crisis — and regretting that we didn’t restrain the bankers when we had the chance.

Joe Conason writes for The New York Observer.

© 2010 Creators.com

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.