India’s Dam Building Bonanza

India is in the middle of a massive hydroelectric dam building program, necessary, its leaders say, to fuel the energy needs of its fast growing economy.

By Kieran Cooke, Climate News NetworkThis piece first appeared at Climate News Network.

ASSAM, NORTHEASTERN INDIA — This region, east of Bangladesh and bordering China to the north, is an area described by politicians as India’s “future powerhouse” and is a key focus point of the country’s dam building programme.

The ambition of planners in New Delhi is not in doubt. So far plans for more than 160 dams – both big and small – have been announced in the northeast, the majority of them to be built in the remote, mountainous state of Arunachal Pradesh and harnessing the waters of the mighty Brahmaputra river and its tributaries.

It’s projected that in total more than 60,000 MW of electricity will be generated from the planned dams. More projects are likely to follow.

Not to be outdone, China, which borders Arunachal Pradesh, is involved in a major dam building programme on its side of the border, also using the waters of the Brahmaputra — which it calls the Yarlung Tsangpo.

Controversy

The dam building programme is highly controversial: critics say it not only ignores geological and ecological factors – it also fails to take into account the impact of climate change in the region.

The Brahmaputra, 10 kilometres wide in places, is one of the world’s major rivers, winding for nearly 3,000 kilometres from the Tibetan Plateau through China, India and Bangladesh before joining with the Ganges and flowing out into the Bay of Bengal.

It is an extremely volatile, tempestuous river system: the Brahmaputra’s waters rise dramatically during monsoon season, causing widespread flooding, erosion and misery for many thousands of mostly subsistence farmers.

Ashwini Saikia is a farmer on the banks of the Brahmaputra river, in the small settlement of Rohomoria in northern Assam. Even now, in pre monsoon season when the river is low, there is the “plop, plop” sound of land falling into the waters.

Erosion fears

“Each year the river has eaten away more and more of my land. Then in 2010 the waters rose so much I lost my house for the fifth time in the last 15 years” says Ashwini.

Ashwini has given up farming and is now being forced to move with his family and livestock — to where, he’s not entirely sure.

Dr Partha Das is an Assamese academic who has been studying the Brahmaputra for several years. He also runs Aaranyak, a locally based environmental NGO.

“The dam building programme has many question marks hanging over it including the fact that the northeast is a highly seismic region, with an earthquake in 1950 completely altering the geological structure of the Brahmaputra river basin,” he says.

Climate change impacts

“Then there is the whole question of climate change, which has scarcely been mentioned by the planners,” Dr Das says. “Already we’re seeing an increase in intense rainfall events that are accelerating the high rate of soil erosion and landslides in mountainous regions. And as temperatures rise and glaciers melt on the Tibetan Plateau and in the Himalayas, river flow levels — at least in the short term — are likely to increase.”

The Indian government defends its dam building programme, saying the power generated will mean that the country will be able to wean itself off its dependence on coal for energy, most of it low quality and extremely polluting.

But many in the northeast, who have long felt cut off from the rest of India and neglected by central government, are unconvinced by New Delhi’s arguments.

There are accusations that the mostly privately backed dam building projects are money making exercises for the wealthy: most of the power produced will be exported to other parts of India and not used to build up local industries.

Tribal concerns

The northeast is a tribal area: indigenous peoples say the influx of labourers from elsewhere in India is threatening local culture. They say the dams will also lead to more deforestation and threaten some of India’s most important wildlife habitats.

Opponents of the dam building say no proper overall plan has been put in place: though India and China recently reached agreement on sharing various river resources, there is no specific deal on managing the Brahmaputra’s waters.

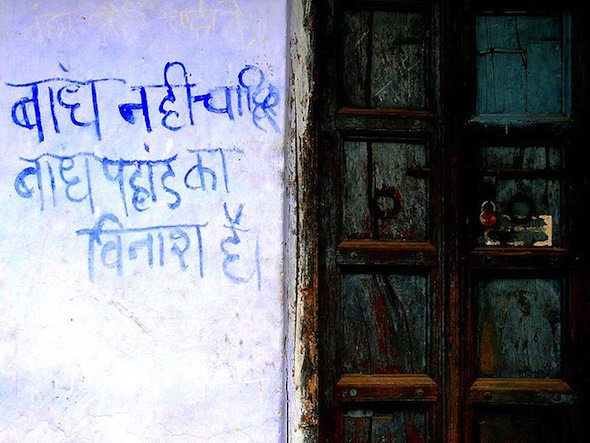

Protests against the dams have been growing, with work on what is India’s biggest dam construction project to date — the 2,000MW Lower Subansiri dam on one of the Brahmaputra’s tributaries — repeatedly held up.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.