Indian Treaties, Oil Pipelines and Presidential Elections: A Tale of Lies, Deception and Hypocrisy

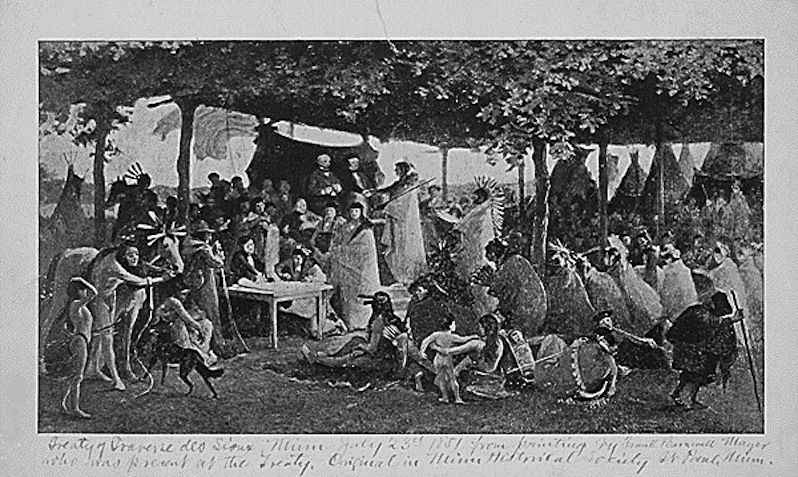

The U.S. government has a long history of breaking promises and dishonoring contracts with Native Americans and other marginalized groups. Hopefully, the next president will change this shameful truth. Treaty of Traverse des Sioux in 1851. Painting by Frank Blackwell Mayer. (National Archives and Records)

Treaty of Traverse des Sioux in 1851. Painting by Frank Blackwell Mayer. (National Archives and Records)

By Jerome Irwin

The American people are about to elect another president to do their bidding. Whoever is chosen will make important decisions about military, corporate and societal issues, and those decisions will help determine the fate of the American people and people thoughout the world. Climate change, economic growth, jobs, environmental protection, basic public welfare, endless world war and terror are at the top of the list of challenges we face. How each gets met, head-on, will depend upon the character of the new commander in chief.

What are the core values of the United States, and which political leader will represent those core values? To examine this, we should look at the many treaties and agreements previous presidents—starting with Thomas Jefferson—have made with Native American nations. We see a long, heart-wrenching tale of lies, deception, betrayal and hypocrisy throughout America’s political and corporate history. The government has broken promises and dishonored contracts, almost since the founding of the United States. As these unethical actions are discovered, like the peeled layers of an odiferous onion, the ugly distortion of core American values brings tears to the eyes. One could argue that these treaties reveal the duplicitous nature of the American character.

Violated treaties have been a nightmare for native, marginalized and oppressed people. No matter what issue pits America’s political and corporate interests against the interests of native nations, a long-standing relationship of deceit and mistrust lies at its heart. This is true whether the issue is the acquisition and transportation of “black gold” or the conveyance of other natural resources via ship, railroad or pipeline.

The most recent example is the conflict between proponents of the Dakota Access pipeline and members of the Great Lakota, Dakota and Nakota Nation. The origins of this conflict go all the way back to the time of first contact between the Great Sioux Nation and America’s military and corporate interests. Ever since Americans and Europeans invaded the sacred territories of the Sioux, it has been one long account of havoc. The constant drive for expansion continues to this day, violently clashing with the Sioux people’s unshakeable resolve to preserve their lands, sovereignty and ways of life. Since the mid 1800s, this issue has led to one war or skirmish after another—including the Dakota War of 1862, Battle of the Rosebud, Battle of Slim Buttes, Battle of the Little Big Horn, 1890 Massacre at Wounded Knee and subsequent 1973 Siege at Wounded Knee.

The 1851 Treaty of Traverse des Sioux is a typical example of the kind of trickery that has been used to divest native nations of their homelands. The U.S. government and corporate fur traders, desiring full control of the Dakota people’s bountiful lands, tricked the Native Americans into ceding all their lands in the state of Iowa, southern and western Minnesota territories and Dakota territories. As one Dakota chief remarked at the time, “I am not a white man. I do not know how to read or write. They pulled me by the blanket and made me put a mark on their leaf of paper. It was not explained to me at all. The money they promised never touched Dakota hands. It all went to the traders.”

For years afterward, the Dakota still believed the promises of white men, even as those Indians watched their children starve. Tellingly, the Dakota name for white people is wasicun, which means “takes the fat,” or “greedy.” That old Dakota word sums up the relationship between the white man, Indians and all oppressed and marginalized peoples.A turning point was reached in the 1860s. The Dakota no longer could take the crush of European settlers pouring into their lands—and could no longer accept the dramatic impact upon traditional Native American ways of life. The economic suffering and social tensions led to what became known, depending upon one’s world view, either as the Dakota War or the Sioux Uprising of 1862.

The event culminated with 38 Dakota warriors being hanged in what remains the largest mass execution on record in American history. Thousands more were transported to “open-air” prisons along the Missouri River at Crow Creek and Niobrara in Nebraska. Chief Little Crow’s skull and scalp ended up displayed in a museum in Pierre, S.D., while the bodies of chiefs Little Six and Medicine Bottle were used for medical study and experimentation. Chief Stand on Clouds’ body was dissected, and his skeleton was cleaned, varnished and given to the Mayo Clinic.

Every year, the descendants of those Dakota victims make a little-known pilgrimage to Minnesota from all over North America. They march along the same 150-mile route that 1,700 of their ancestors were forced to take before being transported to hostile, drought-ridden places in the West. Women, children and elders marched without their husbands, fathers and sons to protect them because the men already had been transported to open-air prisons throughout the Western territories. The men did not see their families for another three years or more. As one of their descendants, Hehaka Cawi Maza, retraced those infamous 150 miles, he said simply, “It’s hard to be an Indian.”

This 1862 tragedy forever will besmirch the honor of the U.S. government and the American and European settlers who ran the Dakota out of their homelands. The dishonor continues today, with white people enjoying the benefits of stolen lands. America is filled with haunted and haunting spirits.

Later in the 19th century, the Indian Peace Commission sought to end the warfare. A series of treaties forced the Sioux off most of their extensive Dakota territories onto more restricted lands of their sacred Paha Sapa (Black Hills). The first treaty, known as the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, was yet another so-called compromise between the vanquished Sioux and their victors. The Sioux agreed to curtail their nomadic ways in return for settling within the protective confines of the Paha Sapa. The Black Hills, according to the treaty, were to be part of a Great Sioux Reservation. This land was set aside in perpetuity for the exclusive use of the Sioux, with no trespassing allowed by any non-Indian.

But with the eventual discovery of gold in the Black Hills, the U.S. government allowed non-Indians to trespass and violate the terms of the treaty. This action, which led to the Indian Wars between the United States and the Sioux Nation (which started in 1874 and lasted until 1876), proved to sovereign-minded native people that this treaty and others like it were not worth the paper upon which they were written. Over the next 150 years, the broken treaties that followed, and the genocide they represent, have turned traditional sovereign lands into virtual open-air prisons, which are politely referred to as reservations and reserves. Like native people everywhere in the world, the Sioux have long memories of many other similar events. Their oral traditions never allow them to forget, and the grievous losses they’ve suffered fuel a resistance that remains unyielding.

At their core, these battles are between two diametrically opposed worldviews: One believes in the inviolate sacredness of a simple handshake, spoken promise or ink touched to paper. The other sees such things as expedient means to an end, and written words hold little significance and can be violated at will. It’s an all-but-unbridgeable divide between those who deem life and land to be sacred, and those who hold sacred only that which feeds their greed, power and control. Both sides are perplexed by the other’s motivations. Reduced to its essence, it’s a clash between those who are moral and those who are immoral, and it’s a perpetual argument over core issues of human dishonesty and truthfulness, disrespect and respect, dishonor and honor, justice and injustice.

The question in the upcoming election is whether American voters are prepared to make a reasoned choice about which side of that argument the next president will take.

Jerome Irwin regularly appears in the alternative press in the United States, Canada and Australia. During the 1960s and early ’70s, he lived with the Dakota and Lakota peoples on the Crow Creek Sioux and Oglala Sioux reservations in South Dakota. He is author of the trilogy, “The Wild Gentle Ones: A Turtle Island Odyssey,” which documents those tribes’ historical plight and the plight of other indigenous peoples on Turtle Island [North America].

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.