Incentives Often Skew Justice in the American Courts, Study Finds

In a disturbing new report, two academics argue that incentives -- from career gains to lab test payments -- may be leading to high numbers of false convictions in American courts. They call for more study, but also for a systemic overhaul.

In a disturbing new report, two academics contend that parts of the American criminal justice system are skewed by incentives that, among other inducements, reward police officers for convictions and pay crime labs based on courtroom outcomes. Those incentives create a significant likelihood of large-scale wrongful convictions.

The study, published in the most recent Criminal Justice Ethics journal, concludes that although the percentage of faked results leading to wrongful convictions is low, the sheer volume of cases handled means there could be some 33,000 false convictions across the country each year. In some instances, the convictions are tied directly to false evidence; in others, they come as guilty pleas as innocent defendants are pressured into plea bargains to avoid exposure to the possibility of a trial conviction on more serious charges. An added issue: state-paid public defender systems that focus on speeding up the legal process more than providing the best legal defense for the accused.

The practices pervert the notion of justice, reducing the court system to an arbiter of gamesmanship. And it often overwhelms public defenders with scant resources to challenge the systemic problems. The authors of the study, Roger Koppl of Syracuse University and Meghan Sacks of Farleigh Dickinson University, argue that “incentivizing” police, prosecutors and crime labs based on conviction or “clear” rates skews the process in unacceptable ways.

Police, prosecutors, and forensic scientists often have an incentive to convict someone, with little or no incentive to convict the right someone. Public defenders often lack sufficient resources and incentives to mount a vigorous defense and cannot, therefore, be viewed as adequate counterweight to the inappropriate incentives available to police, forensic scientists, and prosecutors. … [T]he American criminal justice system thereby creates incentives for false conviction.

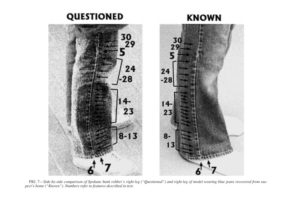

Not all the incentives are clear, nor the errors willful. An expert comparing fingerprints may reach conclusions framed by what he or she knows about the case. For instance, if told the prints came from a suspect who had confessed, the expert may subconsciously overemphasize evidence suggesting the prints match, rather than taking a more detached and distanced review.

There are no easy solutions, Koppl and Sacks argue, while urging more study of the role of incentives in the judicial system.

The number of false convictions could be reduced by structural changes that strengthen the incentive of criminal justice professionals to discriminate between the innocent and the guilty. Incentives matter even when the actors are sincerely motivated to achieve justice. Thus, improved outcomes require structural changes rather than policies meant to “get tough” with overt cheaters and frauds.

But more study doesn’t do much for the thousands of innocent defendants victimized each year by the systemic failures.

—Posted by Scott Martelle.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.