In Conversation with author Chris Abani

The acclaimed novelist and poet, who escaped from imprisonment and torture in his native Nigeria, discusses his new novella about child prostitution and sex trafficking.

In 1990, 10 minutes into the production of his university play “Song of a Broken Flute,” Nigerian literature student Chris Abani found himself under arrest and forced to choose between his own life and the lives of all his fellow student cast members.

Abani, then 21, had already been imprisoned and tortured twice, both times for novels he had written that the Nigerian government regarded as subversive.

His first book, a political thriller published in 1985 when he was 16, envisioned a neo-Nazi takeover of the government. When a coup threatened to topple the country two years later, the authorities decided that Abani’s book had set the blueprint for the uprising and jailed him for six months.

His second novel landed him a full-year stay.

The third time around, having written a play that the government found subversive, Abani was given an ultimatum: sign a document confessing to treason (which carried the death penalty) or sign the death warrant of all his friends in the play.

Abani admitted to treason and was sent — without trial — to death row at a maximum-security prison. He languished there for the next 18 months — six of which were spent in solitary confinement in a six-by-eight-foot hole.

The torture he endured there inspired one of the five volumes of poetry he would subsequently publish: “Kalakuta Republic,” which the playwright Harold Pinter called “the most naked, harrowing expression of prison life and political torture imaginable. Reading them is like being singed by a red hot iron.”

Abani’s home of Nigeria, a former British colony, is the continent’s most populous nation, and also one of the richest, due to its massive petroleum deposits. From 1966 to 1999 (with a brief exception in 1979-83), the country was rocked by a succession of coups and counter-coups led by brutal and corrupt military dictators.

It was amid these continuing violent upheavals that Abani found himself imprisoned three times. And it was not until 1991, “alone, and with nothing,” that he managed to escape to London and continue his writings. In the late ’90s he immigrated to Los Angeles, where he now teaches in the MFA program at Antioch University. He also is an associate professor at UC Riverside.

In 2004 Abani published his most accomplished and critically acclaimed work to date, “GraceLand,” a coming-of-age novel about a 16-year-old Elvis-impersonating youth living in a Nigerian slum who dabbles in crime and ends up brutally tortured by the government. The work won a slew of awards, including the 2005 Hemingway/PEN prize, and was named one of the 25 best books of the year by the Los Angeles Times.

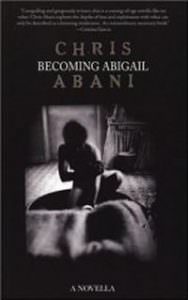

Now 39, Abani is also an accomplished jazz musician who plays saxophone sets at his public poetry performances. Like most educated Nigerians, Abani speaks fluent English, but with an accent that reflects a pidgin combination of British and local Nigerian tongues. Truthdig Publisher Zuade Kaufman sat down with Abani at his home in Los Angeles to talk about his most recent work, “Becoming Abigail,” a novella about a teenage Nigerian brought to London and forced into prostitution by relatives.

Over the course of their conversation, Abani discussed how being tortured affected his writing; the over-romanticization of the word “exile”; and why the first Nigerian on Mars will probably be selling Coca-Cola.

Zuade Kaufman: You were born and raised in Nigeria, but you suffered in the hands of the government there. How would you say these tortured experiences impacted your creativity and what you write about?

Chris Abani: The particulars of my incarceration and what happened to me there, I’m still processing that and so I really don’t know to what extent it’s affected my creativity. The thing is that being that I had been a writer before I went to prison, it’s sort of difficult to gauge. It’s not like I became a writer because I went to prison — where you could really see what impact that experience has had.

It’s had more of an impact on me as a human being, as a philosophical being in the world, and so I think it’s shaped the questions that I ask of life and of myself. And I think one of those questions always is: Is redemption a possibility? And not in a spiritual sense, but in the sense of becoming fully human, in the sense that the Buddhists talk about becoming human. And how far into darkness can a being go and still find their way back to light. And how much is it necessary for there to be darkness for the concept of light to exist.

So I think that it has shaped me as a philosophical being, which I suppose inevitably shapes you as a writer, because I think those are the questions the writers carry through.

You’ve been living in Los Angeles for six years. Do you consider yourself a Nigerian writer living and working abroad, or a Nigerian in exile?

[Laughs.] Exile is a tricky thing because it’s so romanticized as a notion. If I was in exile now it would be a self-imposed exile, since officially I can return to Nigeria, but emotionally I don’t feel like I’m ready for that. So I like to think of myself now as a writer of the world and happen to be living and working in Los Angeles.

Next page: “It always seems like I’m more interested in that moment of when we’re becoming something, rather than the moment when we’re made something.”How does Los Angeles compare to Africa?

Well, the climate is a lot like eastern Nigeria where I grew up — around the Abakaliki Basin. And even though Nigeria is a former British colony, architecturally it takes more from America. If you drive through a small town in America, it literally is like a small town in Nigeria, the way the power lines are overhead, and all that sort of stuff.

The other thing I love about Los Angeles is that it’s so much like Lagos, which used to be the capital of Nigeria. Lagos is a city that constantly seems threatened, as if it’s about to fall apart, and it’s sort of held together purely by a sort of collective will, as it were. Los Angeles is the same way. It’s beset by natural disasters all the time. There’s really no reason for its existence. It’s in the desert, they have to bring water in. And yet it constantly flourishes and grows. So it’s almost like being back home in different ways. So I love it here.

Does Los Angeles nurture you?

Yes, I think it does. I’m gainfully employed here, which is always a big relief. It nurtures me that way. But it also nurtures me psychically. Los Angeles never becomes Los Angeles. It’s always becoming Los Angeles. And so when you live in Los Angeles, you’re always becoming something. And so it’s this amazing place of invention and reinvention. It nurtures me in that kind of artistic way, allowing you to expand and to discover things all the time.

Why did you write “Becoming Abigail” now?

“Becoming Abigail” has stayed with me for a long time. When I was living in London I had read a newspaper article [about] a Nigerian couple [that] had brought over some distant relative ostensibly to help as a nanny and then tried to subject her to prostitution. And when this young girl had refused, they chained her in the back garden in winter, and the neighbors found out and called the police. And it was sort of an isolated incident that stayed in the back of my mind.

[But I read that article] with a great deal of shame, because during the ’80s there was a huge influx of Nigerian immigration to the UK–which makes sense given that Nigeria used to be a UK colony. But this immigration was different from the black immigration of the ’50s and ’60s to the UK, because most of these immigrants were educated middle-class Nigerians whom you would call economic refugees: doctors, lawyers, writers and intellectuals who couldn’t find employment in Nigeria, and had moved en masse to seek work.

It was a difficult conundrum for the English because these were not the working-class immigrants that they had experienced during the ’50s and ’60s. These new immigrants were a literal challenge to the existing middle class in terms of competition. So there’s always some way in which negative media has been spun about us. And so being a Nigerian in that kind of context, every time you read something negative that might have been true you sort of felt–at least I did–some sort of collective shame.

I had [also] read some other article about a judge [in France, who] had sat on an immigration case that involved a 15-year-old girl, and had fallen in love with her, and an illicit affair developed with consequences to both. And I don’t want to discuss [either article] because they’re so connected to the core of the book that it would be giving the book away. But these two stories sort of overlapped, and initially I wrote this as a 2,000-word short story.

And Abigail, this character, just wouldn’t go away. She just kept coming back. Recently, just out of interest, I decided to do a lot of research on the issue of sex trafficking. A lot of my books have this social dimension to them, they connect directly with the world, with real situations. But rather than trying to deal with them as a polemic situation or as a warning about the dangers of this stuff, I always look for the human element of these dimensions; and so that research brought this all together.

For me it was one more way of looking at the notion of the core of becoming human. Because this young woman has so much taken away from her and yet she continues to be human. Even though she exists as a fictional character, when I read it sometimes I think: “Where does this come from, because I don’t remember even writing half of it.”

She humbles me as a person, and that is sort of the impetus behind this work. [That,] and all these amazing people in the world who will not be broken, so that’s why I went there.

Some of my initial [work], like some of the initial books of poetry, dealt with me as a political prisoner and activist, and some of them dealt with my family at war, but more and more, I’ve been breaking away with all my books towards these larger questions: Though [the books] have a social dimension, [they] are more connected with ideas of redemption and the human element — and the becoming.

It always seems like I’m more interested in that moment of when we’re becoming something, rather than the moment when we’re made something. It’s sort of linked to my discovery of Diane Arbus as a photographer. It’s so funny that I should be so consumed by this idea of masculinity but so influenced by female thinkers and writers. All [Diane’s] subjects were so far outside of what we would think of as normal; for her, humans in extreme situations served as metaphors that offered us the possibility of finding out the ways that we become who we are. And that really is becoming. That’s really why I wrote “Becoming Abigail.” But I think that you will find, as a reader, that it doesn’t matter what gender you are, you’re always caught by the remarkable spirit of this young woman in this moment of becoming. Everyone wants her to become something different, which I think is great, because then the book is functioning as a mirror to their own desires and their own becomings.

Next page: “I don’t care about Africa, because Africa doesn’t really exist.”You’ve said you’ve noticed an interest in this subject recently.

Well, social anthropologists have been studying this phenomenon for years in much of Asia. There was a lot of sex tourism where men from Europe would go to the Philippines to have underage sex. And it was talked about almost in a jocular way and nothing was ever done.

But with the fall of the Soviet Union, the poverty of the Eastern Block has made it a European problem. The German government is so aware of its citizens going into, say, Prague to engage in illicit sex with minors that they have a law that allows them to prosecute even though the act [was not] committed on German soil.

And it has begun to crop up in the media quite a bit recently. There’s a movie starring Mira Sorvino, called “Human Trafficking,” which deals with this in the Eastern European context; and the movie “Lilja 4-ever,” which comes out of Sweden, also deals with the issue.

But that’s really what happens when a trauma becomes a Western trauma. As with much of the world’s problems, they become public–or much more of interest–the moment they begin to impact the West.

But I don’t really want to turn it into a political dimension, even though it inevitably always is. But whatever the situation is, at least there is a dialogue around this now. And there’s an attempt to deal with it. Which is only ever good.

Does anyone in America care about Africa?

Well, it’s difficult, because in many ways that word is really what the difficulty is.

No, they don’t care about Africa. I don’t care about Africa, because Africa doesn’t really exist. It’s a continental mass. Africa is hundreds of countries and thousands of ethnicities.

Let me reverse it a little bit. In Nigeria, when I was growing up, America acquired this real mythological status. It became an El Dorado in some ways. But no one really knew what it was. It was called U.S., U.S., U.S., but you don’t realize the complications. It’s really not El Dorado.

Much of the image of the amazingness of America comes from the movies into other cultures. And it’s much the same thing when you reverse it. Much of Africa is presented through poverty, through drought and war. [But] you’re not presenting people, you’re not presenting countries, you’re not presenting complexity, and so people can’t care about an amorphous mass called Africa. But people can care about a young woman from Nigeria called Abigail.

Why did you leave Africa, and do you think you’ll go back?

I didn’t leave Africa, I left Nigeria, and for political reasons. But I go back to the continental mass of Africa all the time. I was just in East Africa; I’ve been in other parts of West Africa since I left.

I’ve never, never left Africa, and I certainly never left what it means to be Ibo. That is something you carry with you.

Is there a Nigerian community here in Los Angeles that you’re connected to?

Yes, Nigerians are everywhere. There’s an old joke, particularly about the Ibos, that when you finally land on Mars, you’re going to find a Nigerian there who has a shop that is selling Coca-Cola — who took a speculative trip 20 years ago and has been waiting for everyone else to arrive.

We differ in many ways from a lot of other nationalities. Because we have 300 languages, English is in many ways people’s first language. Most patterns of immigration create segregated communities because of language access and educational access. But most Nigerians are educated and speak English, so when we arrive in places like the U.S., we don’t congregate into communities. We assimilate very easily.

And because English isn’t an issue, we assimilate based on class. And a Nigerian ambition is to always assimilate upwards. So we are scattered around the country. There are community groups which are based around particular ethnicities, but I don’t belong to any of those. I feel more a part of a community of Nigerian writers and intellectuals who live not just in the U.S. but across the world. It’s sort of a diasporatic, creatively exiled community.

And the Internet is really our meeting place. We have this amazing listserv. Every time I log onto it I feel a sense of pride, because if you log on and say, “Oh I was just in San Diego and I was in a park and I saw a lion,” the flurry of replies on average is just like — wow! [And you get] all these existential questions about what it means to be an African, and never having seen a lion at home, but having seen a lion here. Everything you say turns into this real philosophical debate — it’s incredible in so many ways. And it’s an invigorating place to be. So I belong to that, and I think that’s enough.

I carry what it means to be Nigerian, and I carry what means to be Ibo into all my relationships. I like to think of myself — if there’s such a phrase — as a “global Ibo.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.