I’m Supposed to Protect You From All This

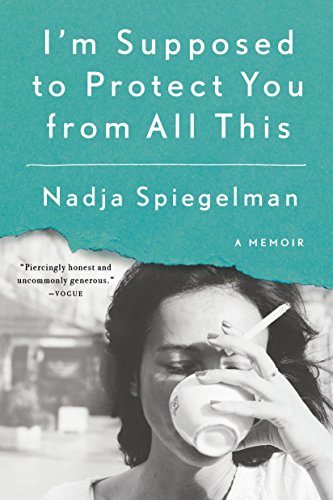

Nadja Spiegelman's new memoir is an attempt to decode her mother's wounds: "The past was always there on her body, but I couldn't see it It was underneath everything else: the blueprint we both carried". (Screen shot via Google Books)

(Screen shot via Google Books)

“I’m Supposed to Protect You From All This: A Memoir” A book by Nadja Spiegelman Reviewed by Elaine Margoli To see long excerpts from “I’m Supposed to Protect You From All This” at Google Books, click here.

The extraordinarily talented 29-year-old Nadja Spiegelman lives for her mother’s love and approval. It threatens to consume her. She seems to feel most alive in her mother’s presence and admits she can’t imagine ever living without her. Her infatuation with her mother began very early. She writes tellingly, “When I was a child, I knew that my mother was a fairy. Not the kind of fairy with gauzy wings and a magic wand, but one with a thrift-store fur coat and ink-stained fingers. There was nothing she couldn’t do. On weekends, she put on safety goggles, grabbed a jigsaw, and remade the cabinets in her bedroom. She ran a hose from her bathroom to the roof to fill my inflatable pool. She helped me build a diorama of the rain forest, carving perfect birds of paradise with her X-Acto blade.”

Her very attractive Parisian-born mother, Françoise Mouly, has been the cover art editor for The New Yorker since 1993 and a publisher of children’s books. Their mother-daughter relationship was always a deeply troubled one for Spiegelman, who was clearly the more sensitive and vulnerable of the two. Spiegelman believed that if she could decode her mother’s troubled past, she might be able to understand her own, and the uneasiness between mother and daughter would lessen. She asked her mother for permission to write a book about her, involving lengthy interviews about her personal history. Spiegelman recalls:

“My mother did not agree right away. She thought about it carefully. And then, having decided, she held nothing back. She let me in. There was nothing I couldn’t ask. She answered me with a searching honesty rare even in the privacy of one’s own thoughts. She made time for me in her overcrowded life. We talked at our kitchen table, in her downstairs office, on the couch. We talked until early morning light streamed through the skylight and the cars started honking again on Canal Street. We went away together, just the two of us, to a country cabin and talked for days.….We talked for years.”

Spiegelman’s father is Art Spiegelman, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “Maus,” the graphic memoir that chronicled his parent’s experiences at Auschwitz and his mother’s suicide 20 years later, when he was only 18. But Spiegelman’s focus is never on her father’s past anguish; it is always about “Mommy.” She admits to a certain blindness when it comes to how she views her mother. She writes, “I did not know my mother was a reckless driver until I was in my twenties, when friends told me so. The things my mother did not see about herself, I did not see either.”

Her mother was often unengaged or missing from her life at crucial moments. She remembers during puberty confiding in her mother that she was ripping out her pubic hair for reasons she didn’t understand. Her mother’s blasé response disturbed and upset her. She recalls her mother constantly berating her about her weight, and taking her brother’s side during arguments, when Spiegelman knew she had done nothing wrong. Her mother never apologized to her for anything, which still rattles Spiegelman, who often felt wrongly accused. If something in their Manhattan apartment was out of place, her mother would fly into a rage. Their family home was often filled with an unbearable tension.

But none of these bad memories stopped Spiegelman from idealizing her mother. Nor did it temper her need for her. When she interviews her mother, she quickly steps into her customary role as pleaser and appeaser to her mother’s fluctuating shifts in mood. She discovers unsettling things about Françoise’s early life. It appears her mother had a relationship with her father that may have transgressed normal boundaries; it is, uncomfortably, never made clear. Her maternal grandmother was controlling and rejecting of Françoise, and she felt terribly unloved and envious of one of her sisters whom she believed was her mother’s favorite. Her parents coerced her into an early abortion, against her will. There are times when Spiegelman recognizes that the memory of these traumas is distressing for her mother, feeling pangs of guilt at her relentless pursuit: “I felt, as I often felt, the violence of my project. What right did I have to reach so deep into her past? I had asked my friends, women between twenty and thirty, if they had asked their mother to tell them their lives in this way. Most said no. Most said they weren’t sure they’d want to know.”

Spiegelman occasionally interrupts her narrative about her mother’s life with her own personal stories. But she hurries through these anecdotes with a self-consciousness that seems to indicate she doesn’t yet feel entitled to take up space on the page. Her mother told her that she held little Nadja constantly when she was a small child, but Spiegelman has no visceral memory of such closeness. She shockingly reveals halfway through the book that she is gay and that her parents are accepting of it, but she has a difficult time sharing this vital part of her identity with many who are close to her. She professes to have a significant other, but we learn nothing about her, or about their relationship. We get no sense of her life as a young adult. She seems buried under her mother’s thumb.

Spiegelman travels to Paris, spending a year with her maternal grandmother in an attempt to fill in the missing pieces of her mother’s life. Her grandmother’s memories frequently contradict her mother’s. Her grandmother claims to have always loved her daughter unconditionally, but does concede that something indecent may have occurred between Spiegelman’s mother and her father. Her grandmother isn’t certain, but seems worried still. Spiegelman recognizes that her mother may have physically escaped her family’s grasp, but, like many victims of trauma, brought her wounded psyche with her to Manhattan. She writes with tender empathy of her mother’s wounds: “The past was always there on her body, but I couldn’t see it. It was in the scars that I traced with a fingertip as a child, in the strange things that set off her anger. It was even in my own body, a feeling of damage and danger that had no name and explanation. It was underneath everything else: the blueprint we both carried.”

By the end of her searing narrative, we are rooting for Spiegelman. And there are the small glimmers of hope to hold onto. While in Paris with her grandmother, Spiegelman is struck by the realization that her grandmother and mother share a certain coldness, and a peculiar distortion of priorities. A tendency to show more empathy for a wounded pet than an injured child. A relentless self-absorption. We feel exhilarated by Spiegelman’s new awareness because we recognize immediately that it is the first time she has allowed herself to genuinely grapple with the notion that her mother is a deeply flawed being and not the magical fairy she once imagined her to be. It is a significant step in her own journey toward a more mature and independent adulthood.

Elaine Margolin is a freelance book critic whose work has appeared in numerous newspapers and literary journals including The Washington Post, San Francisco Chronicle, Jerusalem Post and Women’s Review of Books. She is based in New York.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.