ICE’s Human Smuggling Operation Has a More Sinister Objective

The agency claims it's pursuing coyotes and their U.S. employers, but a new investigation reveals its true targets are parents and children. Master Steve Rapport / Flickr

Master Steve Rapport / Flickr

It was August 2016 when Wilson got the call, from an unknown number. A worker from the Office of Refugee Resettlement, the agency that oversees the custody of migrant children, was on the line.

Wilson’s 17-year-old daughter, Yensi, had just crossed the U.S. border alone. She’d been a toddler the last time Wilson saw her, just before he fled death threats from a cartel in their native Guatemala.

Would he consider giving Yensi a home while she went to immigration court?

Wilson was shocked, he said, and had no idea his daughter had been thinking about crossing the border. But now that she was here, in a Texas shelter for migrant children, Wilson only thought about bringing her home as soon as possible.

He rushed to gather all the paperwork, including a copy of his Guatemalan passport and billing statements confirming his address. About three months later, he picked Yensi up at the airport. He hadn’t considered the fact that he had lived for nearly 20 years without legal status.

“I simply thought about helping my daughter,” Wilson said.

Less than nine months after that, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents showed up at the address he’d given the government and detained him.

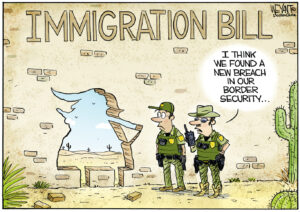

At that time, ICE was rounding, ICE rounded up more than 400 people, including sponsors of child migrants, as part of what it called a crackdown on human smuggling. ICE officials said the operation, called the Human Smuggling Disruption Initiative, targeted people who paid for coyotes to bring children across the border.

However, a review of the operation by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting casts doubt on that official narrative. A search of more than 1,400 smuggling-related cases filed in federal court in the seven months during and after the operation turned up only one case that was clearly connected to the program. In two other cases, parents were convicted on smuggling charges after paying someone to bring their children to the U.S., but court records don’t mention the ICE investigation by name.

The Trump administration went on to scale up the tactic in April 2018, sharing information on all parents and other sponsors collected by the Office of Refugee Resettlement with ICE, not just those officials suspected of smuggling. As a result, the agency that’s supposed to be aiding children in the immigration system has helped ICE deport their parents.

By December, ICE said the agency had made 170 arrests based on the information sharing. That new policy is the subject of a federal lawsuit filed in Virginia that says the Trump administration is using migrant children as bait to arrest their undocumented family members.

ICE can no longer use the information sharing to arrest and deport parents and sponsors, at least through September, when the government’s fiscal year ends. Congressional Democrats made that a key sticking point in the immigration compromise that ended the government shutdown earlier this year.

Wilson insists he had no knowledge that Yensi planned to enter the United States, and says he never hired smugglers to bring her across the border. Now, he faces the possibility of deportation this year.

The lack of prosecutions supports suspicions from immigration lawyers and advocates who say the operation was a cover for ICE to use unaccompanied minors as bait to find and arrest undocumented immigrants.

When Congress reorganized border security agencies after 9/11, lawmakers assigned the care of unaccompanied minors to the Office of Refugee Resettlement, separate from ICE’s responsibility to enforce immigration laws. Social workers and lawyers could tell parents that they wouldn’t be targeted for deportation if they came forward to claim their children.

ICE’s three-month anti-smuggling campaign, and the information-sharing policy with the Office of Refugee Resettlement, changed all that.

“I have to tell these people, well it’s a matter of luck,” said Wilson’s attorney, Justin Mixon. “I can’t tell you it’s risk-free.”

The moment Wilson was handcuffed, he said, an ICE agent told him he was going to be deported.

“They used the kids,” Wilson said, “to get to parents like me.”

The anti-smuggling operation

Wilson never thought he’d leave Guatemala. A skilled mechanic and electrician, he graduated from college in the 1990s. Soon after opening his own business, a local cartel approached him about working for them.

When he refused, the death threats began. Wilson moved to a nearby town, but the letters continued. One letter said Wilson had 24 hours to leave Guatemala.

“It was obvious they were going to kill me,” Wilson said. Reveal is not using his full name due to concerns for his safety if he is deported back to Guatemala, where the cartel is still active.

Wilson crossed the border into the United States, leaving behind his wife and his daughter, Yensi. But a few weeks after arriving, he was arrested during an immigration raid and deported. A few months later, he crossed again.

Wilson and Yensi’s mother eventually split up. In the last two decades, Wilson has built a life in Philadelphia. He works at a landscaping company, climbing up trees while carrying a chainsaw. He remarried, and together he and his wife were raising a blended family of four when he got the call about Yensi. They live in a light blue house on a quiet tree-lined street. School photos of the kids, ranging in age from 9 years to 20 months old, line the walls inside.

Through the years, Wilson stayed in touch with Yensi through phone calls and text messages. He sent her money regularly to pay for her schooling. Yensi lived with Wilson’s sister, but decided to leave Guatemala when her aunt got married. She wanted to be with her dad. Yensi spent three months at a shelter overseen by the Office of Refugee Resettlement in Texas before joining Wilson in the fall of 2016. She fell into a routine at her new home, going to high school and learning English.

Then on Aug. 17, 2017, while Wilson was at work, he got another call.

This time it was his wife. ICE agents were at their door and needed Wilson to sign some papers related to Yensi.

He hadn’t even reached the front door of his house when the agents surrounded him.

At the ICE office, Wilson was detained in a holding area with other immigrants. They started talking, and a few others said they had also recently sponsored young relatives who crossed the border.

Mixon suspects Wilson, who doesn’t have a criminal record, was targeted by ICE because he agreed to sponsor Yensi. ICE declined to identify people arrested in Pennsylvania during the operation, but acknowledged that agents assigned to the human smuggling operation were working in Pennsylvania in August 2017, the same month that Wilson was arrested.

“He was living here peacefully and doing his thing and staying out of trouble,” Mixon said. “There was no reason for ICE or any other law enforcement agency to go after him.”

Immigrant advocates began noticing similar arrests all over the country that summer. Jennifer Podkul, policy director for Kids in Need of Defense, said, “It took a lot of digging to figure out what was going on and what was happening.”

“It wasn’t until later that we realized that it was an operation that had a formal name and it was planned,” she said.

ICE first acknowledged the new program in 2017. ICE deputy press secretary Jennifer Elzea said the operation, conducted by ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations division, was designed “to disrupt and dismantle end-to-end the illicit pathways used by transnational criminal organizations and human smuggling facilitators.” ICE said the investigation would combat the “constant humanitarian threat” of child smuggling.

KIND released a report on the program in December 2017 that detailed cases in which ICE arrested parents and interrogated them about the smugglers they’d hired to bring their children into the country, despite parents’ protests that they hadn’t paid anyone. The group also noted the “likelihood that children will interpret their own search for protection as the cause of their parent’s vulnerability to deportation or prosecution.”

Eight immigrant rights groups also sent a complaint to the Department of Homeland Security. The groups said that ICE’s smuggling initiative violated the rights of immigrant families, and used children “as bait to ensnare the parents and caregivers seeking to protect them.”

“From an ethical sort of human rights perspective,” said Heidi Altman, policy director of the National Immigrant Justice Center, “it is just nonsensical, not to mention cruel, for the administration to target parents and then use as a justification the disruption of smuggling rings.”

‘He will be held accountable’

“Undocumented Guatemalan Sentenced For Paying Smugglers To Bring Unaccompanied Minor From Guatemala To The United States,” the Justice Department announced in February 2018. ICE had arrested a Jacksonville, Florida, man and now he’d been sentenced to seven months in federal prison.

“He endangered a child’s life with a dangerous and unlawful journey into the United States, and now he will be held accountable,” James C. Spero, a special agent with Homeland Security Investigations, said in the press release.

ICE agents specifically credited the Human Smuggling Disruption Initiative with uncovering the crime. It was the only case Reveal found that mentioned the operation by name.

In court filings, ICE special agents Donald Wells and Michael Wood detail how the operation went down.

It began in South Texas on June 29, 2017. A Border Patrol officer encountered a 16-year-old boy named Santiago and asked him where he was going. The boy said he’d come from Guatemala and was going to live with his brother-in-law, Miguel Pacheco-Lopez, in Jacksonville. He gave the officer an address.

A week later, Wells and Wood knocked on the door of the two-story house on a residential street on the city’s northern outskirts. A man said Pacheco-Lopez wasn’t home, but he let the agents inside, where Wells and Wood found five more men from Indonesia and Guatemala. The agents arrested all six for immigration violations.

A Chinese couple arrived and said the men all worked for them at their Japanese steakhouse near the airport. Wells and Wood drove to the restaurant and found it closed, but an employee outside said the owners had told the staff to go and wait at a Walmart across the street.

The manhunt ended in a grocery aisle. Wood and Wells stopped a Hispanic male, Wells wrote, who admitted his name was Pacheco-Lopez and he was in the country without documents. They arrested him and drove him across town for an interview.

Raised by farmers in Guatemala, Pacheco-Lopez grew up speaking K’iche’, a Mayan language he never learned to read or write. In 2016, he left his wife and two daughters behind to earn money to support the family, court records state. He arrived in Florida, where he washed dishes at the Japanese steakhouse and lived rent-free in the owners’ house along with his co-workers.

His father-in-law “begged him and begged him” to help his wife’s brother, Santiago, come to the U.S. to get an education, according to a statement his attorney gave in court. After a few months, Pacheco-Lopez had saved enough to send back. Inside the same Walmart where he was eventually arrested, he visited a MoneyGram counter and wired about $6,000 to help pay for Santiago’s journey. He didn’t know who the family paid to take the boy across, his lawyer said.

At first, Pacheco-Lopez planned to fight the charge he faced, for “encouraging or inducing” the boy to cross illegally. But after four months in jail he pleaded guilty.

Throughout the case, he denied ever hiring a smuggler. His lawyer wrote that her client “regrets his actions, not because he begrudges the benefit to Santiago and the extended family, but because of the pain of his incarceration and the impact it has had on his family.”

By the time he was sentenced, Pacheco-Lopez had been jailed for seven months, unable to earn money to send to his wife and children in Guatemala. A judge sentenced him to time served, plus one week and a $100 fine. One month later, ICE returned him to Guatemala.

ICE officials said they didn’t track what happened to the more than 400 people arrested, and it’s unclear how many were deported. The agency said 38 cases were sent to prosecutors, but the Department of Justice couldn’t say how many of those resulted in convictions.

The Pacheco-Lopez case was the sole smuggling conviction directly connected to the operation that Reveal could find: time served plus deportation for a man who never directly hired any smugglers. Pacheco-Lopez’s nephew led ICE agents not just to his uncle, but also to six other undocumented coworkers who had nothing to do with human smuggling.

Since the operation ended, a federal appeals court has called its entire legal premise into question: In an unrelated case, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in December that the federal law against “encouraging or inducing” someone to cross the border was unconstitutional.

The court noted that a grandmother encouraging her grandson to overstay his visa to be near her, or an immigration activist telling people not to accept deportation, would all be vulnerable to prosecution.

“Criminalizing expression like this threatens almost anyone willing to weigh in on the debate” about immigration policy, the court wrote.

Waiting for a court date

Wilson was released from ICE custody the same day he was arrested. He’s got a court hearing in August, and is challenging his deportation. He still works trimming trees, while his wife stays home to take care of the kids.

On a recent Saturday morning, Wilson sat on his living room couch, his hands clasped in his lap as he thought about what will happen to his family if he’s deported. He says he doesn’t understand why the government would release his daughter to him and arrest him a year later, knowing he is responsible for her.

“What will happen to my family?” he asks. “How will they live? Who will pay the rent, the bills? Who will take them to school?”

Moments later, the kids begin to wake up. Wilson smiles as they giggle and run around upstairs before coming down the staircase. “Dad, I’m hungry!” says 6-year-old Jazmin.

“Yeah? Let’s see what we can do about that,” Wilson tells her. Within a few minutes, he prepares bowls of cereal for the kids. He sits at the head of the table, surrounded by them.

If he had known helping Yensi would put him at risk for deportation, he would have tried to have a family member with legal status sponsor her, Wilson says. But even if that wasn’t an option, he would have helped her anyway.

“I couldn’t leave her alone, abandoned,” he said. “As a father, I would have taken the risk no matter what.”

Aura Bogado contributed reporting to this story.

This story was edited by Andrew Donohue and copy edited by Stephanie Rice.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.