How to Save Affirmative Action

The Supreme Court might force defenders of affirmative action to adopt less conventional but equally effective means of promoting diversity on college campuses.

As the nation moves closer to deciding whether to re-elect its first African-American president in a campaign that has often exhibited the ugliest of racial overtones, the issue of race has also taken center stage at the Supreme Court. The controversy before the court concerns a constitutional challenge to the affirmative action program at the University of Texas, and the conventional wisdom is that the high tribunal will overturn the Texas program as it continues its sharp lurch to the right. Yet the court might also force defenders of affirmative action to adopt less conventional but equally effective means of promoting diversity on college campuses.

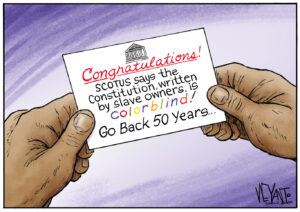

At first glance, it’s hard to see the conventional wisdom going awry. Even in its long-ago liberal days, the Supreme Court took an ambivalent position on race-based affirmative action, invalidating numerical quotas in higher education while grudgingly allowing mild forms of preference to stand. And now, if the views expressed during the Oct.10 oral argument in Fisher v. University of Texas are any indication, the court’s five conservative justices appear poised to outlaw racial preferences once and for all.

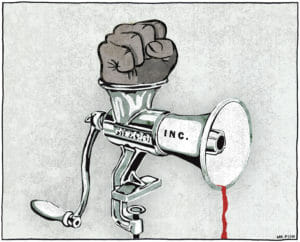

From the perspective of the American right, which has loathed affirmative action since the term was coined by President Kennedy in a 1961 executive order barring discrimination in federal contracting, Fisher is the perfect vehicle for halting an experiment in left-wing social engineering that never should have gained traction in the first place. After graduating from a Houston-area high school, a young white woman — Abigail Fisher — motivated only by the understandable goal of securing the best available education, sought admission to UT for fall 2008. As a state resident, her application was subject to the university’s “10 percent” program, which guaranteed admission to all students graduating in the top 10 percent of their high school class. In 2008, this program accounted for roughly 85 percent of UT’s first-year students.

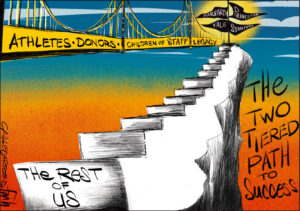

But because Fisher lacked the requisite class rank, her application was evaluated under a second-tier index applied to the remaining in-state applicants that permitted the university to consider race as one factor along with others such as academic and personal achievements for the purpose of increasing diversity in the student body. When her application was denied, Fisher sued, contending UT had discriminated against her on the basis of race in violation of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

Although the Supreme Court had approved a similar admissions policy at the University of Michigan in 2003, it agreed to take up Fisher’s case after a federal appeals panel, following past precedent, ruled against her. In oral argument, the court’s conservatives, led first by Chief Justice John Roberts and then joined by Justices Antonin Scalia, Anthony Kennedy and Samuel Alito (Justice Clarence Thomas, as usual, remained mute), attacked the Texas plan as vague, illogical and unfair.

Among all the criticisms, perhaps the most cutting was delivered by Alito, who mocked the university’s acknowledged practice of recruiting affluent but less academically gifted minority students to help fill the second-tier applicant pool. Such practices, Alito suggested, amounted to an abandonment of the original purpose of affirmative action — helping the disadvantaged. And with the abandonment of that purpose, Alito implied, race-based affirmative action in any iteration could no longer be justified.

To those who have toiled long and hard to combat the legacy of slavery and racial inequality, Alito’s comments rang with self-righteous hypocrisy but, sadly, also carried the appearance of finality. By the argument’s conclusion, affirmative action seemed destined to be gutted.

Yet despite the grim prognosis, the conventional wisdom may well prove lacking, not in terms of how the court ultimately rules in Fisher (we are, after all, dealing with the most reactionary Supreme Court since the early 1930s) but in one vital and largely overlooked respect — that by putting an end to racial preferences, the court’s conservatives unwittingly could help unleash an even broader and more progressive form of affirmative action, founded not on race but on social class. At least, that’s the hope of a small group of policy wonks led by Richard D. Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at the Washington, D.C.-based Century Foundation.

In an Op-Ed published in The Wall Street Journal the day of the Fisher argument and in a longer study available on the foundation’s website, Kahlenberg reasons that a redesign of affirmative action emphasizing income and class would benefit deserving and underprivileged minority students as well as their underprivileged white working-class counterparts, enabling progressives at once to retake the moral high ground in the debates over college admissions while avoiding the constitutional pitfalls of equal protection that are so easily exploited by the right with race-based models. And most important of all, according to Kahlenberg, the economic approach — which has been implemented to varying degrees by a range of public universities and colleges in seven state systems — yields nearly as much racial diversity among students as the traditional variety.

As promising as Kahlenberg’s proposals are, they have yet to win widespread support among defenders of race-based affirmative action, some of whom dispute his findings and understandably refuse to give up the fight in the face of vicious Republican assaults on minority rights. Many affirmative action supporters are also looking for a boost from the re-election of Barack Obama. The administration participated in Fisher on behalf of the university as an “amicus” (friend of the court) and, if given the opportunity, Obama presumably would appoint judges to the Supreme Court more open to upholding racial preferences.

But even assuming Obama is re-elected — an outcome that is less assured by new polls coming in — counting on him to come to the rescue and decisively alter the balance on an issue the Supreme Court has never easily embraced is a risky strategy. As in any protracted struggle, whether a military conflict, a presidential campaign or a clash over civil and constitutional rights, the ability to adapt is often the key to survival and often the difference between winning and losing. Seen in that light, the long-term survival of affirmative action may indeed require a movement away from race to the more-inclusive concept of social class, no matter who sits in the White House.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.