How South Korea Handles Piracy

The rise of piracy in the Arabian Sea has raised difficult legal questions, but there's little ambiguity about how the accused will be handled by South Korea.

Five Somali men, facing the possibility of life in prison, will soon be tried in South Korea for piracy that occurred thousands of miles away. They have been taken to the southern city of Busan, where warrants were issued for their arrest.

The alleged pirates were apprehended 800 miles off the coast of Somalia after the South Korean-owned Samho Jewelry, hijacked in the Arabian Sea, was stormed by South Korean navy commandos. The commandos rescued all of the vessel’s 21 officers and crew members, eight of whom were reported to be South Koreans.

Eight Somalis were killed and the remaining five brought into custody. The ship’s captain remains in critical condition after being shot, allegedly by the Somalis who took over his vessel.

Dealing with pirates has long left legal professionals with a bleak calculus. Captured pirates who come from a state without a functioning judicial system (such as Somalia) and commit their crimes in international waters are in a legal gray area. It’s difficult to decide how and where they should be tried and who should foot the bill for it all. This has resulted in what some consider a culture of impunity for pirates.

There’s little ambiguity about how the accused will be handled in South Korea. Article 6 of the country’s criminal law code allows noncitizens to be tried in South Korea for crimes committed against South Koreans on foreign soil. Article 340 of the code specifically rules on hijackings at sea. There is a precedent of 10 Chinese fishermen in 1996 being tried and convicted for robbing a South Korean boat.

“I think it’s only natural that we ourselves deal with the pirates who inflicted harm on our people and attacked our forces,” said Foreign Minister Kim Sung-hwan.

This case could set a new precedent for how pirates are dealt with, as other countries might follow South Korea’s lead by dragging accused men back within their own borders to face trial.

As an alternative, Jack Lang, a special adviser to the United Nations on maritime piracy, is seeking the creation of special courts to process alleged pirates. Somalia is unable to handle the cases internally and it’s difficult to find third countries willing to host trials.

According to a statement by the U.N. Security Council, “Ninety per cent of all pirates captured by national navies were released because no states were prepared to accept them and no jurisdiction was prepared to prosecute them.” Lang argues for setting up courts in Somalia and Tanzania.

The International Chamber of Commerce’s International Maritime Bureau has found that incidents of piracy have increased every year for the last four years. Record highs were set in 2010 in the number of people captured. This has taken place despite increased sea patrols by foreign vessels in pirate hot spots. The South Korean example may inject new ideas into what seems a hopeless situation.

The attendant contrasts of the alleged pirates’ trial in South Korea will be sharp. They have been taken from a country with no government to one with an ambitious leadership where everything gleams, from a fractious, clan-based failed state to a unified, nationalistic democracy.

Processing the alleged pirates presents complications for South Korea, and any other country that follows such a strategy is likely to face similar problems. According to Kim Hyun-soo, professor of international law at Inha University, “The expense and resources associated with the handling of the pirates may be high, but unavoidable. The government has to take care of the consular service and interpretation assistance, transportation and housing for the accused, transportation for the witnesses, identification of the victims and their presence at the court, and the cost associated with the lengthy custody of the pirates.”

The South Korean administration will probably be willing to handle the costs. This act of decisive protection of South Korean citizens has given a boost to public morale after ill-fated 2010 incidents like the March sinking of the warship Cheonan and November’s shelling of Yeonpyeong Island by North Korea. Many South Koreans have expressed fear that their nation is being seen internationally as a weak state that may be attacked without forceful response.

According to a column in the Joongang Daily, one of the main newspapers in a country where people still actually read newspapers, “It was a face-saving event not only for the government, but for the entire nation. We take comfort from the victorious news from the Gulf of Aden that this nation is willing to stake its name and life for its people.”

South Korea is already home to the world’s only prison designed to exclusively hold foreign prisoners, and the alleged pirates presumably will be held in the facility, if convicted. In the years before 2010, the number of foreigners in South Korean jails increased sharply to 1,500, leading to the opening of the Cheonan Correctional Institution for Foreign Nationals.

Prisoners there receive classes in the Korean language and culture and may choose between Korean and Western meals. The prison also has a library with some books in foreign languages and a satellite television system that carries foreign-language programs.

For some critics, the Cheonan prison has highlighted South Korea’s discomfort with outsiders. Many questioned the need for a facility for foreign nationals when foreigners made up only 1,500 of the country’s prison population of more than 62,000. Others complained that foreigners were receiving unfair benefits in the form of education and food choices that are not available in typical South Korean prisons.

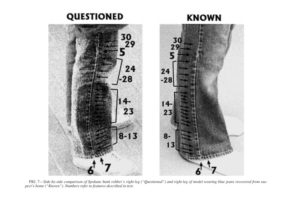

South Korean authorities are now questioning the accused Somalis. While the arrested men have admitted to taking part in the hijacking, the details of the incident, particularly who shot the ship’s captain, have yet to be clarified.

South Korea’s approach to maritime piracy may be useful to consider, although it depends in part on the country’s unique character. The existence of a prison created to isolate foreign prisoners and South Korea’s historical suspicion of outsiders expedited the case, facilitating public approval for the apprehension and trial of the accused.

Jack Lang’s proposed alternative would standardize the method of handling alleged pirates and not leave them vulnerable to the idiosyncrasies of individual states. Piracy is an issue that disregards state boundaries, and could therefore use a global solution.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.