How Kafkaesque Bureaucrats Are Ruining Education

Last week the Los Angeles Unified School District, the second-largest in the nation, opened its doors for the new school year. The following story is a sobering tale of bureaucracy run amok, to the detriment of its schoolchildren.The following story is a sobering tale of bureaucracy run amok, to the detriment of schoolchildren.

Last week the Los Angeles Unified School District, the second-largest in the nation, opened its doors to more than 640,000 students for the new school year. The following story is a sobering tale of bureaucracy run amok, to the detriment of its schoolchildren.

When John Deasy took over the Los Angeles Unified School District in 2011, he promised a “world-class” education for all students. A cornerstone of his plan has been to tie teachers’ jobs and salaries to their students’ scores on standardized tests. For the past two years Deasy has driven his vision relentlessly from his 24th floor executive suite in the district’s downtown headquarters, through a half dozen layers of administrators, to nearly 900 Los Angeles schools.

But on July 2, 2013, a new school board was sworn in, and the majority seems skeptical of Deasy’s business model. Matthew Kogan, an educator who walked precincts for the board’s newest member, teacher Monica Ratliff, explained, “It’s a very narrow model and there’s a lot of hostile things about it towards teachers.”

Despite intense pressure from the district headquarters to boost scores, academic performance is shockingly low and it trails behind students in most other large California districts. Just 39 percent of LAUSD students are proficient in math and only 41 percent are proficient in English (though their scores have improved since 2010). Nearly four in 10 LAUSD students fail to graduate from high school, and African-American students are nearly twice as likely to drop out as whites.

Deasy is quick to blame the schools for students’ poor performance but the real problem is right under his nose. As my experience attests, the villains aren’t the teachers, as many believe, but often are power-hungry district bureaucrats who set their own agenda and are accountable to no one.

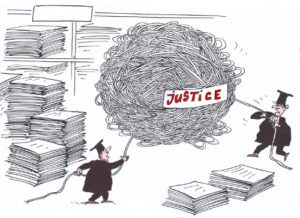

The story that I relate here portrays a microcosm of what paralyzes the LAUSD and every other large urban school district in America. After studying schools for 40 years, I know that concentrating power in the district office may give the illusion of control, but it dooms reforms at the schools where it counts because it emasculates principals, burns out teachers, infuriates the teachers union and drives away community support.

Several months ago, after a bruising confrontation with LAUSD bureaucrats, my co-teacher, Avis Ridley-Thomas, and I were forced to abandon a decade-old partnership between UCLA and the LAUSD that had served some of Los Angeles’ neediest students. Ridley-Thomas, who founded the Los Angeles City Attorney’s Dispute Resolution Program, and I taught and trained hundreds of UCLA undergraduates to mediate disputes, and we sent them to schools to resolve conflicts among middle and high school students. The UCLA undergrads also teach the younger students how to defuse tensions for themselves through peer mediation, and they act as role models — big brothers and sisters — opening the younger students’ eyes to the larger world of higher education with field trips to UCLA.

Mediation is an idea of profound importance because resolving conflict person-to-person without using force has been proven to produce trust and lasting solutions. The results have been remarkable, and it has not cost LAUSD a dime. The UCLA students have resolved more than 2,000 disputes, often in highly charged school situations that include potential suicides, bullying and name calling, any of which can easily escalate into violence. One UCLA student told me:

“It is an awesome experience. This one girl was starting to cut herself but she couldn’t talk to anyone. We sat down with her and she started crying because three boys she’d known in elementary school were bullying her, calling her fat and ugly. After she calmed down we met with the boys who had no idea of the harm they were causing. We had a third mediation with all of them and the boys apologized. It is amazing to see something like this happen right before your eyes.”

When we were forced to end the program, we also had to abandon plans for an even more ambitious project to establish schools as community centers for conflict resolution, where teachers, parents, students and police officers would mediate neighborhood disputes after hours. This would bring those groups together in some novel ways that would strengthen the fabric of the community.

West Los Angeles College agreed to share the model with the other eight campuses in the Los Angeles Community College District and a greatly expanded network of LAUSD schools to increase the impact. We brought funders together at the schools with partners at the Los Angeles Police Department, UCLA, West Los Angeles College and the Institute for Nonviolence in Los Angeles, knowing that if it succeeded, it could be a model for the entire city.

But on Feb. 1, 2013, everything stopped. An LAUSD employee — let’s call her Ms. Jones (not her real name) — invoked the district’s burdensome and complex procedures to effectively drive us away. The UCLA students were upset, but the real victims were the children in the schools who were deprived of a powerful learning experience. The other less tangible loss was what could have been a major step bringing mediation to Los Angeles neighborhoods, where violence often rules how conflicts are settled.The seeds of trouble were planted about a week before UCLA’s fall quarter ended in December 2012, when our students had been fully trained and were ready to go to work in our six partner schools in January, after their holiday break. Jones, focusing on one of the schools, emailed that UCLA would have to submit agreements comprising 19 pages, including insurance coverage for malpractice, liability, auto, workers’ compensation and sexual abuse, plus fingerprinting and clearance forms, TB tests, scopes of work, student schedules and supervision plans.

These forms would have to be signed by Jones, her supervisor, the principal of the school that was the subject of her review, and my dean at UCLA’s graduate school of education. This was hardly good news because I knew from past experience the nightmare that LAUSD red tape can be. Time was critical and the stakes were high. When the UCLA students returned in January, they expected to go to their campuses to mediate, as agreed to by the schools, and if the students failed to complete the winter quarter requirements, even through no fault of their own, they would fail both the fall and winter courses, which are linked in a series.

My heart sank as I riffled through the 19 pages of forms. They were full of legal and district jargon, redundancies, references to us as “contractors” with warnings not to offer cash to district employees to get their business. Having students get TB tests takes only a couple of days, but I was advised that fingerprinting to get clearances by the U.S. Department of Justice can take from two days to a month and cost $78 per student at the UCLA Police Department; we would have to find $2,500 to cover this unforeseen expense.

During the holidays I started the paperwork at UCLA, and over the course of the next two weeks called and emailed Jones several times but got no response. I left messages saying I sent the “scope of work” document she requested and that we were scheduled to have our students at the schools Friday, Jan. 18, less than two weeks away. She finally emailed saying she needed all the materials.

This could not be accomplished quickly because LAUSD’s insurance requirements were being reviewed by UCLA’s Office of Risk Management, the university’s campus counsel would have to review them, and students’ fingerprint results were only trickling in. Now we had just a week before the students were due to report to the schools.

I called Jones again and again and asked whether we could expedite the process, but she was firm — everyone had to be cleared. I appealed to a counselor at one of the other schools where our students were about to begin their mediation work, which turned out to be a big mistake. Within an hour I had an email from Jones, informing me that she had now drawn the second school in the growing snarl of red tape. “You will need to duplicate this process,” she wrote.

It was beginning to feel Kafkaesque, as the bureaucratic powers became surreal. Over the next two weeks there were more reviews, more delays, an error Jones made that had to be corrected. This dragged on many more days. On Jan. 28, 10 days after our students had been scheduled to report to the schools, I emailed Jones. “Would you let me know where we are?” I asked. Predictably, there was no answer.

The next morning I called Jones, who then said that Ridley-Thomas and I would need to be fingerprinted for clearance and have TB tests. I told Jones that one of her colleagues had said that was not necessary if we didn’t have contact with students. These tests are meant to protect schoolchildren, but people who have very limited to no contact with students, including parents, delivery people, the postman or people like us, come and go routinely under a waiver to the policy. That did not matter to Jones.

As a last resort, I called the principal of the school, who had publicly praised the program, and left a message asking him to intervene to save it. Later that day, he left a voice mail that there was little he could do, as “I am just a school-based principal.” He said he would get back to me but never did.

That afternoon we pulled the UCLA students out of the LAUSD schools and placed them at other campuses where we knew we could work cooperatively with the administrators.

The undergrads were furious when they heard the news. One said to me: “I’m not going to lie; I was really angry that I could not work at the school. I promised the kids I would come back and get to know them. This was a big group of kids, and I feel like l lied to them and deserted them.”A few days later, on Feb. 26, I wrote a detailed letter to Deasy, offering to meet to resolve the issue. His administrative assistant assured me that she would hand deliver it to him later in the day. The superintendent has never replied.

Deasy confirmed what I have experienced with the LAUSD over the years: District bureaucrats like Jones run the show and aren’t accountable to anyone, so people at the schools, where the real work of education gets done, are afraid of them. What happened with Jones is not an isolated case.

I have studied oppressive management like the LAUSD’s in a wide range of organizations — schools, colleges, police departments, unions and corporations. No matter what kind of enterprise it is, the results are the same: Intimidating employees to comply with directives from their bosses — or else — teaches them to behave the same way. A mid-level manager in one company with a long history of coercing its employees told me, “Sure there are seven people over me who kick me in the butt, but I have a dozen people under me that I kick too.”

In time, an organization develops a culture — a set of beliefs — that supports this dysfunctional behavior, turning once-eager problem solvers into cowed minions. It may be that Jones, her colleague and the principal of the school were also once energetic and positive people. But what is clear is how the indelible imprint of the LAUSD’s toxic culture — intimidating and blaming others, shirking work and avoiding risk — shapes its employees’ behavior.

It is ironic that the LAUSD jettisoned a program that teaches students about taking responsibility and initiative, building trusting relationships, and resolving conflicts without coercion or violence. Imagine how much more productive the LAUSD could be if only its administrators could learn those same lessons.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.