How George H.W. Bush Got Us Stuck in the Mideast

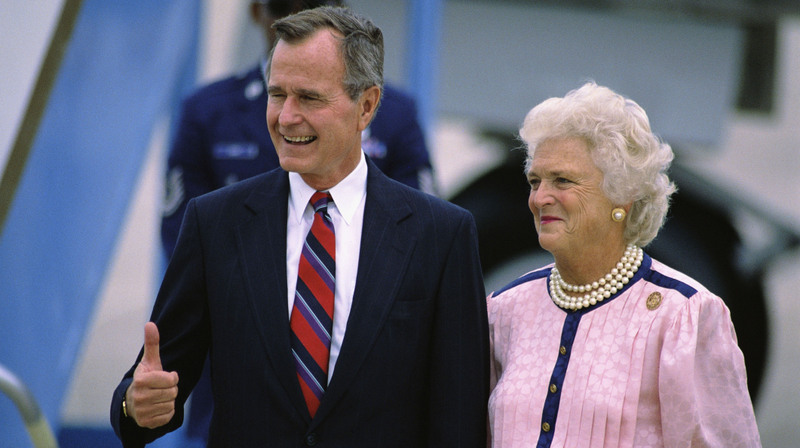

On the occasion of the death of former president, I’d like to reflect on the meaning of his presidency for American foreign policy in the region. George H.W. Bush and his wife, Barbara. (Esther / CC BY-ND 2.0)

George H.W. Bush and his wife, Barbara. (Esther / CC BY-ND 2.0)

On the occasion of the death of George H.W. Bush, I’d like to reflect on the meaning of his presidency for American foreign policy in the Middle East.

Bush was the last representative of the old Republican Party of wealthy Northeast businessmen and Midwestern farmers and small town dwellers, before the religious right took over the party. That the Southern Baptists and other evangelicals did not form part of his base allowed Bush to view the Israeli-Palestinian conflict more dispassionately than have any of his successors.

Bush admitted that he struggled with having a political vision. In 1989, the first year of his presidency, he experienced the windfall of the fall of the Berlin Wall. He called for a new world order, but it was unclear what the content of that order would be except the dominance of capital and national interest. He appeared to hope (unrealistically) that the charity sector (“a thousand points of light”) could make up for the steep decline in government-provided services impelled by the Reagan tax cuts. Workers and the poor were not his priority.

Bush was a pragmatist, and was happy to negotiate with Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev over several key issues. He once pulled Gorbachev aside and explained to him that he was surrounded by “intellectual thugs” and that he might have to say harsh things about the Soviet Union publicly but that Gorbachev shouldn’t pay attention to it.

A particularly important negotiation was over the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan. The last Soviet tanks went over Friendship Bridge from Afghanistan to Uzbekistan in February of 1989. But Gorbachev and the Soviet officer corps left behind the dictator Najeeb Ullah, who was attempting to form a national front between the Afghan Communists (mainly Persian-speaking Tajiks) and the rebel groups (many of them Pushtun). The rebel mujahideen had been backed by the CIA with $5 billion a year in the late 1980s, which was matched by Saudi Arabia. Al-Qaida had grown up in Aghanistan as an Arab volunteer adjunct to the mujahideen, which initially received Saudi popular contributions raised by socialite Osama bin Laden from mosque congregations in the kingdom, an activity blessed by the Reagan administration.

In return for the Soviets completely withdrawing from Afghan affairs, Bush pledged to stop supplying the mujahideen, or fundamentalist holy warriors. The last shipment of weaponry went to them in late 1991. When Bill Clinton came in, in 1992, the United States was completely out of Afghanistan, as the mujahideen nevertheless swept into Kabul and established a fundamentalist government.

It may have been the right thing for Bush to do, to get the Soviets out of Afghanistan by withdrawing the U.S. from it as well. But, given that Ronald Reagan had nurtured the religious funadamentalist forces, they become increasingly important. The subsequent power vacuum produced a series of fundamentalist governments. The mujahideen, flush with U.S. and Saudi money, became dominant for a while. But after Bush cut them off, Pakistan began funding a faction of them that became the Taliban. In turn, the Taliban offered refuge to bin Laden and al-Qaida.

On Aug. 2, 1990, Saddam Hussein of Iraq invaded the small oil kingdom of Kuwait and announced its incorporation into Iraq as the “19th province.” Bush’s realist circles, including his secretary of state, James Baker, were initially unsure they should do anything about this act of naked aggression. Realist principles in political science warn against liberal humanitarianism in foreign policy and ask if national interest is affected and whether a peer power can take advantage. The Kuwait crisis did not have a direct impact on the U.S., since Saddam intended to pump Kuwaiti oil just as the Kuwaitis had. The episode did not involve the Soviet Union, then, in any case, on its last legs.

It is said that British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher convinced Bush that something must be done. Thatcher believed that great powers rule by cowing lesser ones, and that if Saddam were not put down, then a whole range of third-world challengers would dare emerge to take on the industrialized democracies. Ironically, the insouciant realist Bush had his greatest success in organizing a liberal internationalist response to Saddam’s aggression.

Bush, having decided to go to war, got the right to base troops in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province from King Fahd. He worked the phones and got British, French and other buy-in. Even the Arab League joined him. He put together the biggest international military coalition since WWII, and expelled Iraq from little Kuwait with some of the biggest tank battles since WWII (along with intensive aerial bombardment). Egypt was allowed to enter Kuwait City first so as to give the impression that Arabs were taking care of their own affairs.

In order to put together his coalition, Bush had to promise the British, the French and others, that he would stop with the expulsion of the Iraqis from Kuwait and would not go on to do regime change in Baghdad. He did, however, embargo weapons sales to Iraq in the 1990s, a move emulated by the Clinton administration. The embargo on chlorine (which can be used to make chemical weapons) stopped Iraqi water purification efforts (to which it is essential) and led to the deaths of many children from dirty water. The death toll was horrible, but was exaggerated by critics to 500,000, which later studies have found too high. This statistic was quoted by bin Laden as partial justification for his 9/11 attacks.

Bush had called on the Iraqis to rise up against Saddam. The Kurds did, in the north, but then Saddam survived and they feared he would come for them with poison gas. They fled to higher ground, where they eventually would run out of food. Bush established a no-fly zone over Iraqi Kurdistan to prevent Saddam’s armored corps from coming up and massacring them. The Shiites also rose up but were put down, leading to volatile sectarian relations and, after 2003, massive reprisal killings that destabilized Iraq.

Bush used the respect and fear in which he was held in the region after the Gulf War. He pushed for peace in Israel-Palestine. He declined to underwrite Israeli squatter settlements in the West Bank with loan guarantees. He positioned the U.S. for backing the later Oslo Accords, which the Israeli center and left embraced but which the Likud Party that came to be dominated by Binyamin Netanyahu completely rejected.

Bush or his successors leased Prince Sultan Airbase in Saudi Arabia for the over-lights of the no-fly zone, which allowed bin Laden to claim that the U.S. was militarily occupying the Muslim holy land, one of his stated reasons for the later Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

The U.S. became the Great Power in the Gulf, finally supplanting the British, but unable again to extricate itself from Gulf affairs. It was stuck.

Bush showed pragmatism and leadership, and did not overplay his hand with the declining Soviet Union. Bush made the U.S. the security guarantor for the Gulf, a role it still maintains. The Reagan policies of backing Afghan fundamentalists and backing Saddam’s Arab nationalist Baath Party against Iran had set in play forces that Bush could not contain, and which went on, after his presidency, to have a crucial impact on the United States.

———

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.