Haute Love, High Fashion

Bergé admits that his own nature was controlling, and he makes no apology for it. Indeed, he makes no apology for anything in his life. And therein lies something of a mystery. We are not allowed to imagine what Saint Laurent saw in this man—except an enabler.I think Saint Laurent had something like an artist’s spirit, but he was obliged to operate in a world that is almost the definition of ephemera.

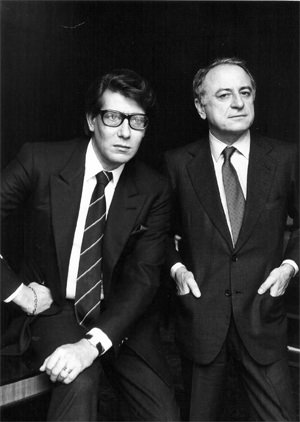

They were the oddest of couples: Yves Saint Laurent, the world-class fashion designer—flighty, depressive, manically hard-working and for a time both a drug addict and an alcoholic — and Pierre Bergé, the couturier’s business and life partner for a half century—a stolid, determinedly unsentimental man who elliptically recounts their story in Pierre Thoretton’s disappointing documentary “L’Amour Fou.”

The occasion for Bergé’s reflections is the auction of the pair’s vast assemblage of art objects a little more than two years ago. I use the word assemblage in preference to collection because it appears to have been put together impulsively rather than through the operation of a rational plan or as a firm statement of taste—not that that affected the amount realized at auction, which was something close to $500 million.

That figure is not mentioned in the film. Neither is the fact that prices must have been favorably affected by the celebrity of the men who owned the 733 items placed on sale. As Thoretton’s camera pans about the rooms in which the objects were displayed—often enough as they are being packed for transfer to the auction house—you gain a powerful sense of pure clutter. Nothing in their arrangement suggests that this or that piece is more significant than the others. In a way that’s charming—these guys just liked to live surrounded by pretty (and valuable) things. In a way it’s disquieting. What’s the point of grand-scale acquisition if you don’t in some way impute relative value (or affection) for all that stuff? There is a whiff of the Collyer brothers about this duo, except that they are hoarding not old newspapers but Picassos and Renoirs and Brancusis—priceless icons of modernism.

To a considerable degree, this film is an attempt to enhance the importance of Bergé in the creation of Saint Laurent’s celebrity. People inside the Parisian fashion world knew what he meant to the designer; he kept the business organized, grew it to world-class status and, above all, gave his lover the privacy to more or less work himself to death. This was OK with the melancholy and illusive Saint Laurent. The film reports that he was happy only twice a year, when, inevitably, his shows received triumphant receptions from the fashion press and the rest of the tiny, hothouse fashionista world. Within two days, of course, his euphoria faded, and he would retreat for a brief time into one of the homes that he and Bergé owned in Morocco or Normandy, after which, naturally, he started work on his next collection.

Bergé admits that his own nature was controlling, and he makes no apology for it. Indeed, he makes no apology for anything in his life. And therein lies something of a mystery. We are not allowed to imagine what Saint Laurent saw in this man—except an enabler. What we see of him is a rather ponderous figure, always impeccably clad in a well-cut, obviously expensive suit, insisting that he has no sentimental interest in the collection that he’s selling. Or, more or less, in Saint Laurent himself or the half century they spent together. He manages occasionally to utter the proper mourner’s words, but in totally dispassionate tones. He and a few other intimates pay tribute to the “genius” they served, but they cannot explicate it. Perhaps, one begins to think, because genius was not requisite to Saint Laurent’s activities.

This suspicion grows when Thoretton shows us footage from a variety of Saint Laurent’s shows. The dresses he creates are not meant to be worn anywhere but on a runway. You can’t imagine any woman getting out of a taxi wearing them or sitting down to dinner in them—if, indeed, a woman could actually sit down in them. Design, at this level, is essentially a publicity stunt, a way of establishing a “look,” be it Russianate, for example, or a knockoff of Mondrian’s manner. It is for Saint Laurent (and others) to translate these radical statements into clothing that real-life women can actually wear without looking foolish or absurdly vulnerable. That’s where the money is—tons of it, obviously. Which says nothing of the perfume lines the house developed and where, one glumly suspects, there’s even more dough.

And that’s where the insistence on the designer’s “artistry” begins to look more than a little fishy. An artist naturally needs to make money and to gain attention. But he is also hoping for something more, which is, of course, immortality. This is something that cannot be gained in the rag trade, with its incessant pressure to come up with something new and attention-grabbing every six months. I think Saint Laurent, who was not a well-educated man, had something like an artist’s spirit—he was a bold conceptualizer and he had a hand gifted enough to realize those conceptions in an often dazzling manner—but he was obliged to operate in a world that is almost the definition of ephemera. It is also, of course, a big money world (not healthy for artists) and one that is utterly vacuous. It is no wonder that the man was chronically depressed and subject to addictive behavior.

This is not quite a tragedy. But there is an implicit sadness in the tale this movie tells. Bergé was too close to, and too profitably engaged in, the fashion world to point out its pitfalls to his partner—if he even noticed them. And Thoretton is too distant from it to perform a similar function in his film. They have to accept it on its own half-hysterical, half-stupefying terms. As does whatever audience this film might have.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.