Ground Zero in the Land of Opportunity

Right at the point when they are most needed, our second-chance institutions are being severely threatened Across the country, community colleges, adult schools and literacy programs are reporting record enrollments at the same time they have to trim staff, classes and services.

Opportunity

is a key word in the American story, one that is embedded in the political speech of the right and left alike. And central to the story, a major subplot, is that we are the land of opportunity not only for those fresh out of the gate — young people, first-time job seekers, those poised to climb another rung on the mobility ladder — but also for people who have not done so well educationally or economically the initial time around. We are a country of second chances. We believe deeply that with hard work we can triumph over adversity. Popular culture is rich with tales of the underdog, the come-from-behind winner — accounts of personal redemption, rags-to-riches stories. In “Ragged Dick,” Horatio Alger’s novel about an enterprising bootblack, one of the author’s fictitious benefactors offers the following rosy observation about upward mobility in the United States: “In this free country poverty is no bar to a man’s advancement.” The belief that individual effort can override social circumstances runs deep in the national psyche. It’s in Ben Franklin, in Alger’s immensely popular 19th-century novels, and it is a central tenet in conservative social policy today.

I have been spending the last several years at ground zero for the second chance, an urban community college serving the poorest population in a city with many concentrations of poverty. About 60 percent of the students are on financial aid. Because of a subpar education or schooling cut short, 90 percent need to take one or more remedial courses in English, reading or mathematics. A fair number have been through the criminal justice system.

As I have gotten to know these students, the numbers come alive. Many had chaotic childhoods, went to underperforming schools and never finished high school. With low-level skills, they have had an awful time in the labor market: short-term jobs, long stretches of unemployment, no health care. Many, the young ones included, have health problems that are inadequately treated if treated at all. I remember during my first few days on the campus noticing the number of people who walked with a limp or an irregular gait.

For much of my professional life, I have worked with such students, and I was brought to this campus as part of a research team charged with exploring the barriers to their success. My time here has allowed me to see directly the power of a second chance, but also has laid bare the mythology around it, the complex nature of opportunity in the United States when you’re already behind the educational and economic eight ball. To make matters worse, the community college I’m visiting has been hit with budget cuts and has had to limit course offerings and services and turn some new students away.

It’s telling, I think, that an issue last year of the influential conservative magazine National Review posed this question in bold print on its cover: “What’s Wrong With Horatio Alger?” Above the question the young Alger protagonist sits forlorn on a park bench, his shoeshine kit unused, an untied bundle of newspapers next to him, unsold. The standard political discourse from the right contains no such question about mobility. The party line is that the market if left alone will produce the opportunity for people to advance, that the current sour economy — though worrisome and painful — will correct itself if commerce and innovation are allowed to thrive, and that the gap between rich and poor is, in itself, not a sign of any basic malfunction or injustice, for there are always income disparities in capitalism. For government to draw on the money some people have earned to assist those who are less fortunate is to interfere with market principles, dampen the raw energy of capitalism and foster dependency. The opportunity to advance is always there for those who work hard. This is a seamless story, made plausible by our deep belief in upward mobility.

But the author of the lead article in National Review cites statistics that pretty much all economists across the ideological spectrum confirm: Upward mobility for people at the bottom rungs of the income ladder, limited during the best of times, is significantly diminished. Breaking the numbers out by race, the author writes of “a national tragedy,” that “black and white children grow up in entirely different economic worlds.”

The writer goes on to say that “living up to our values requires policymakers … to focus on increasing upward relative mobility from the bottom.”

The Economist, not as fiscally conservative as National Review but in the same free-market ballpark, put it even more strongly in an April 2011 cover story, “What’s wrong with America’s economy?” The writers say that the real danger to the American economy is chronic, ingrained joblessness that is related to our social and economic structure: tens of millions of young, marginally educated people who drift in and out of low-paid, dead-end jobs and older low-skilled displaced workers, unable to find employment as industries transform and jobs disappear. This situation places a huge and — if left alone — intractable drag on the economy. Therefore, the writers recommend comprehensive occupational, educational and social services, for America spends “much less as a share of GDP than almost any other rich country” on policies to get the hard-to-employ into the labor market.

Many of the people I meet at the college face hardships beyond what education alone can remedy — housing, health care, child care and, bottom line, basic employment. But improving English or math, or gaining a GED certificate, or an occupational skill or a postsecondary degree would contribute to their economic stability and have personal benefits as well. There are a few people who seem to be marking time, but most listen intently as an instructor explains the air-supply system in a diesel engine, or the way to sew supports into an evening dress or how to solve a quadratic equation. And they do and redo an assignment until they get it right. Hope and desire are brimming. Many of the students say this is the first time school has meant anything to them. More than a few talk about turning their lives around. It doesn’t take long to imagine the kind of society we would have if more people had this opportunity. Yet, right at the point when they are most needed, our second-chance institutions are being severely threatened. Across the country, community colleges, adult schools and literacy programs are reporting record enrollments at the same time they have to trim staff, classes and services. A number of colleges can offer only a smattering of courses in the summer. On the flip side of this coin are rural and semirural institutions that have lost enrollment over the years because of changing demographic patterns. They are facing closure, even though for those still in the community, they are the only resource of their kind available. And the public library — an iconic American institution — is reducing hours and staff and closing local branches. This is at a time when two-thirds of the nation’s libraries provide the only free Internet access in their communities — and when government and employment information and forms are increasingly going online.

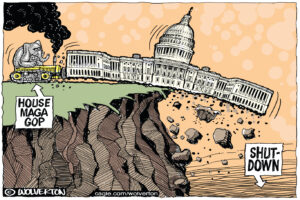

The immediate cause of these cuts is the terrible recession that began in 2008. Policymakers face “unprecedented challenges” and “have no other choice” but to make reductions in education. Doing more with less has become, in the words of Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, “the new normal.” The word austerity has entered our national conversation with a vengeance. As I write this, the Los Angeles Unified School District is slashing its adult education budget to one-quarter of the previous year’s allocation, affecting 24 community schools, serving more than 250,000 people.

I don’t dispute the immense difficulty of budgeting in a recession, nor the fact that education spending includes waste that should be eliminated. But when our situation is represented as inevitable and normal, the recession becomes a catastrophe without culpability. The civic and moral dimension of both the causes of the recession and the way policymakers respond to it is neutralized.

What is especially worthy of scrutiny is the role right-wing economic ideology is playing in these policy deliberations. Anti-government, anti-welfare state, anti-tax, this ideology forcefully undercuts broad-scale public responses to hardship. Such efforts are tarred as a “redistribution of wealth,” moving money, as Rep. Paul Ryan puts it, from the “makers” to the “takers.” Decisions are made on a ledger sheet profoundly bounded by simplistic assumptions about economics and opportunity as well as naive, often bigoted, beliefs about people who need help.

For the most part conservatives support the idea of second-chance educational and training programs, but many would insist that they trim their costs and slash the financial aid that enables students to attend them. These policymakers also resist the kinds of services that many students need to continue their education: health and child care, rehabilitation programs and housing. So they support the idea of a second chance while undercutting most of what makes it possible.

Every conservative affirms equal opportunity. Yet, in no realistic sense of the word is there anything like equal opportunity toward the bottom of the income ladder — and some argue that opportunity is eroding toward the middle as well. Recent studies show that parental income has a greater effect on children’s success in America than in other developed countries. As that writer in National Review noted, low-income kids live in a different economic world. Many of the students I’ve taught at UCLA who come from well-to-do families grew up in a world of museums, music lessons, tutoring, sports programs, travel, up-to-date educational technologies, and after-school and summer programs geared toward the arts or sciences. All this is a supplement to attending good to exceptional public or private schools. Because their parents are educated, they can provide all kinds of assistance with homework, with navigating school, with advocacy. These parents are doing everything possible to create maximum opportunity for their kids, often with considerable anxiety and expense. There’s no faulting them; poor parents would do the same if they could. But it would require quite a distortion to see young people from affluent and poor backgrounds as having an equal opportunity at academic and career success. To legitimize their view of the economy and society, then, conservatives have to justify advantage.

One way to account for unequal opportunity is to claim that intelligence is a factor, and that the families at the lower end of things are there because they’re not that bright — so various compensatory programs, in fact, won’t help that much. You’ll certainly hear this kind of talk in private, and a few bold pundits like Charles Murray, of “The Bell Curve” fame, say it in public. But scientifically it doesn’t hold water, and it is so politically unpalatable that few elected officials would risk uttering it.

Another way to explain away inequality — one that has a long history in the United States and is still very much with us — is the moral argument. People are at the lower end of the economy because of a failure of character, they engage in counterproductive behavior, lack a work ethic, they don’t complete things, and so on. They are a drain on the system, gaming it, on the dole. Since Ronald Reagan’s infamous “welfare queen” invocation, conservative political discourse has been brimming with such imagery, as the 2012 GOP primary demonstrated. There is both a theory of the social order and good, old-fashioned prejudice at play here — and both are enhanced by the social isolation of the rich from the poor.

I don’t want to minimize the deep philosophical differences between a conservative and liberal perspective on social issues, but I do think that some conservatives would be surprised to see firsthand the work ethic, the lack of excuses for previous bad behavior and blunders, the self-reliance, and multiple responsibilities and schedules of the students I’ve met. I’ve been working with one group that begin classes at 7 in the morning, then work, participate in student government, go to the library to study and leave in the evening — usually by public transportation — for homes that are anything but stable (thus the refuge of the library). One young man is currently homeless, sleeping in his inoperable car parked at a friend’s family’s house. He’s at school every day by 6 a.m. to clean up and get his day in order.

Of course there are people at their school who are drifting, drawing what resources they can, sometimes deluding themselves, sometimes consciously gaming the system. The students I’m mentoring can point them out in a heartbeat because they are not the norm. Furthermore, and it’s a sign of the times that I even have to write this, such behaviors appear across the socioeconomic landscape. The deplorable thing is the degree to which moral and character flaws are disproportionately attributed to poor people. But if you are able to penetrate the ideological fog and actually enter other people’s lives, you’ll witness a quite different and much more complex human reality.

Finally, the right justifies advantage by defining opportunity as an individual phenomenon and represents obstacles to mobility as clear and local and within one’s personal power to overcome. This definition yields a particular version of the rags to riches story, which takes us back to the young Horatio Alger character sitting on that park bench. Conservatives use rise-from-hardship narratives to great effect, for they confirm their claims about the ever-presence of opportunity, regardless of background. But one of the most striking things about conservative celebrations of mobility is that they are accounts of hardship with almost no feel of hardship to them. They reflect a kind of opportunity that exists only in fiction. Obstacles receive brief mention — if they’re mentioned at all — and anger, doubt and despair are virtually absent. You won’t see the home health care worker whose back is a wreck or the guys at bitter loose ends when the factory closes. You won’t see people exhausted, shuttling between two or more jobs to make a living or the anxious scramble for minimal health care for their kids.

The right’s stories present a world stripped of the physical and moral insult of poverty. Characters move upward, driven by self-reliance, optimism, faith and responsibility. Though there might be an occasional reference to teachers or employers who were impressed with the candidate’s qualities, the explanations for the person’s achievements rest pretty much within his or her individual spirit. The one exception is parents: They are usually mentioned as the source of virtue. Family values as the core of economic mobility.

In the Alger originals, the lucky break, the fortuitous encounter, is key to the enterprising hero’s ascent. Alger’s narrator writes: “Not many boys can expect an uninterrupted course of prosperity when thrown upon their own exertions.” It’s worth dwelling on this sentence, for there’s little play of chance and good fortune in the contemporary conservative version. Luck’s got nothing to do with it. And you surely will not hear a whisper about legislation or social movements that may have enhanced opportunity, opened a door or removed an obstacle. It would be hard to find a more radically individual portrait of achievement.

The stories of mobility I know differ greatly from the conservative script. To be sure, there is hard work and perseverance and faith — sometimes deeply religious faith. But many people with these same characteristics don’t make it out of poverty. Discrimination is intractable, or the local economy is devastated to the core, or the consequences of poor education cannot be overcome, or one’s health gives out or family ties (and, often, tragedy) overwhelm.

The people who do succeed — and their gains are typically modest — often tell stories of success mixed with setbacks, of two steps forward and one back. Such stories reveal anger and nagging worry, or compromise and ambivalence, or a bruising confrontation with one’s real or imagined inadequacies — “falling down within me,” as one woman in an adult literacy program put it. This is the lived experience of social class. No wonder that these truer stories typically give great significance to help of some kind, both private and public. A relative, a friend, or a minister lends a hand. Family and community social networks open up an opportunity. A local occupational center provides training. The government’s safety net — food stamps and welfare, Medicaid, public housing — protects one from devastation.

It is, then, a tight bundle of reductive economic and social theory, a fanciful definition of opportunity and negative beliefs about the poor that have become such a force in truly difficult budget negotiations, and there does not seem to be an equally powerful economic and moral counter-voice in those deliberations to check it.

One of the programs I visited at the college enrolls low-skilled adults in a mix of math and English courses with training in the construction trades. During the orientation, the director would ask the students to talk and write about what brought them back to school. The economic motive was a big one. “I want to get some money to take care of myself,” said a woman who was also eager to earn her high school diploma. A young man said flat out, “I don’t want to work a crappy job all my life.” But there were a lot of other reasons these people had come back to school. They wanted to “learn more,” “be a role model for my kids,” “get a career to support my daughter,” “develop better social skills and better speech,” “have a better life,” “turn my life around,” “be somebody in this world.” This is what the students at ground zero in the land of opportunity have to say. Who, in turn, will speak for them?

To read an excerpt from Mike Rose’s latest book, “Back to School: Why Everyone Deserves a Second Chance at Education,” click here.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.