FX Plays the Race Card

In a new reality series, a black family and a white family switch skin colors. But do they switch perspectives? UPDATE: The show's producers, under fire from its participants, alter parts of the show that were deceptive.

UPDATE:The show’s producers, under fire from its participants, alter parts of the show that were deceptive.Start of original essay

Black.White.,Ӕ a six-part series that debuted last night on the FX channel, bills itself as groundbreaking and provocative television, a fearless exploration of racial tension in America.

In theory, it could be.

Its premise is provocative enough: Two families — one black, one white — are made to live in the same house for six weeks in the San Fernando Valley, with camera crews following them around as they grapple with the impact of skin color in America.

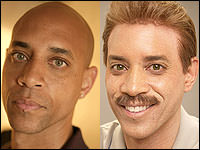

Plus, theres a twist: Before almost every day of shooting, the families undergo three hours of makeup magic to effect a complete swap of their racial identities. Brian, Renee and Nick Sparks, a black family from Atlanta, get spray-painted pale skin, light-colored wigs and everything else it will take for them to pass as white. The white family — Bruno Marcotulli, his girlfriend Carmen Wurgel, and CarmenҒs daughter Rose — are all made up to look black.

And the conceit works, thanks to the show’s makeup experts, whose previous credits include the race-swapping comedy White Chicks,Ӕ the gender-bending film Big MommaӒs House and the spectacularly gruesome ԓThe Passion of the Christ. Made up in skin drag, both families are let loose on the streets of Los Angeles, followed by either hidden cameras or a crew that tells curious passersby only that they are ԓshooting a documentary on families.

As the series unfolds, we watch 18-year-old Rose — adorable in a shellacked wig and slathered in enough dark foundation to almost obliterate her teenage acne — try to make her way through an Afro-centric spoken-word poetry workshop. Forty-one-year-old Brian Sparks, on the other hand, hidden behind an unfortunate but very effective red mustache, sits in on a focus group on racial attitudes among white men, and must endure hearing one of the men in the group admitting that after he shakes a black manԒs hand, he feels compelled to wash his own. Meanwhile, 48-year-old Carmen — an attractive blond location scout with heavily aerobicized triceps and a proud liberal heritage (my parents were active in the civil rights movementӔ) — has to shop for outfits for herself and her boyfriend for their visit to an all-black church. Carmens choice? An African-print dashiki.

If all this sounds like a Chappelle skit gone to graduate school, thatҒs because it sort of is.

Gangsta-rapper-turned-actor Ice Cube served as the shows co-executive producer, in addition to writing its theme song, ғRace Card. R.J. Cutler, who made the groundbreaking 1993 documentary ԓThe War Room, a behind-the-scenes look at Bill ClintonԒs first presidential campaign, is the one who developed the idea. Cutler hesitates to call the film a documentary, but he has also taken great pains to distance the series from the much maligned and wholly contrived world of reality TV, calling it instead a reality experiment.Ӕ As you might imagine, the project has not been free of controversy. Nelson George, an eminent hip-hop journalist, activist and himself a producer of a documentary about race in America, went so far as to tell the Los Angeles Times that this kind of television is phony and dangerous.Ӕ

Phony, maybe, but not dangerous. The white adults — Bruno and Carmen — are a parody of smug ignorance, fond of expressions like IӒm coming from a place ofŔ and I want to speak with an open heart.Ӕ But its Bruno, a 47-year-old substitute teacher — the kind who you just know tries to high-five the kids and doesnҒt even notice their snickers –whose behavior most begs for a smackdown.

Bruno is full of hokum about personal responsibilityӔ and getting back from the universe what you give to the universe,Ӕ and good or bad energy, but what he is most excited about, as he tells his incredulous housemates, is the chance to be called a niggerӔ by an unsuspecting stranger.

He says it, and then he repeats. Again. Bruno just loves the sound it makes, and his new makeup gives him the idea that its now OK for him to use it whenever he wants, but word is still so taboo — and in the wrong hands, ugly — that my dutifully self-conscious white self actually cringed while typing it. Conventional wisdom, aka common sense, dictates that you shouldnҒt use the word even if youre black — and even then, itҒs pronounced n-i-g-g-a — just the way Ice Cube himself did 20 years ago when he and the hip- hop group N.W.A. (Niggas With Attitude) released their breakout album Straight Outta Compton.Ӕ If youre white — and not a teenager, in which case the lines are a bit blurrier — then you donҒt use the N-word, not if you value your teeth.

Unless youre Bruno, arguably the most irksome white man to appear on our television screens since the last presidential address. Part of what makes Bruno so repellent, and part of what makes the show worth watching, is that in addition to his smug unwillingness to listen to a word another person says, heҒs also personally invested in proving that America is a colorblind society, one in which any word that is fair game to blacks should be fair game to him as well. This, even as the Sparkses try to convince him, first gamely and then through gritted teeth, that he is denying their daily experiences. Listen,Ӕ they keep saying to him. I am listening,Ӕ he insists, but IӒm also trying to enlighten you!

If Bruno is invested — some would say obsessed — with proving that the Sparkses exaggerate their own experiences, the Sparkses themselves are much more sympathetic. Renee, 38, is a dental office manager who pretty much gives up on Carmen after she calls Carmen out on the inappropriateness of addressing her as ԓYo, bitch, even as a joke. Instead of apologizing for her gauche behavior, Carmen throws a tear-stained tantrum, insisting, of course, that sheԒs coming from a good place. You took one for the team, Boo,Ӕ Renees husband, Brian , tells her later that night.

One gets the sense that Brian is also grimly ғtaking one for the team. A computer contractor, his chief personality trait is patience, made manifest by his refusal to ever once clock Bruno over the head with a hammer. Brian goes undercover as a bartender in a sports bar. Hidden once more behind his expertly applied light paint and mustache, Brian gets to hear what white bigots say when they think theyԒre among their own kind. A patron tells him this is a great neighborhood, one of the last safe [read: white] bastions in the city.Ӕ Brian does not seem surprised or dismayed by the revelation; this is exactly what he expected. But his wife, Renee, in one of the series best and most discomfiting scenes, comes in without makeup to confront the clientele and find out for herself just how rotten they are.

Still, itҒs Carmens daughter, Rose, who is treated as the seriesҒ hero, if only by default. Bright-eyed and articulate, she frets about the ethics of presenting a false face to the world, moderates intra-house squabbles and recognizes her mothers ignorance without ever condemning it. Young Rose is open-minded, thoughtful, painfully aware of her own ignorance ҅ and essentially full of shit. This girl was made to mug: She never forgets the camera, and she performs each new observation about her own role in the experimentӔ as if she were auditioning for a film role (which it turns out she is; a year after filming, Rose is trying to get work as an actress).

Rose milks the drama for all that its worth. And so do the filmmakers, but one wishes theyҒd have a little more faith in their own material. Instead of just letting events unravel, they keep steering their victims situations with maximized dramatic potential, until finally you feel as if youҒre being harangued by a modern-day carnival barker: WATCH Bruno and Carmen, in black drag, feel uncomfortable at the redneck cowboy bar! SNICKER as Carmen buys a dashiki for her first visit to a black church! CRINGE, as Nick faces his first etiquette class!

Not only do these situations feel forced, they often actually are forced: Even Roses class, for example, where she agonizes about whether to come clean with the young poets about her fake identity, is a setup. The kids there are all black, to push the whole racial divide thing, but in reality, spoken-word workshops are usually as diverse and multicultural as Los Angeles claims to be. Poetri and Juren Smith, the husband-and-wife team running the workshop, told the Los Angeles Times that he, Poetri, was asked to put together an all-black group to fit the needs of the show, and that he knew RoseҒs secret the whole time.

Its a bit self-defeating, especially since the whole point about racial (and ethnic) tensions is that daily life provides more than enough to work with. But the two familiesҒ daily lives are whats missing, since the whole situation is contrived from the start: You never see them argue (or agree) on what television show to watch, what food to cook, whose turn it is to take out the garbage, or who drives the car. WeҒre watching reality,Ӕ sure, but its one in which all the conflict is orchestrated around artificial circumstances, far removed from the real-life interactions that both fuel racial tension and ultimately serve as our only means to combat it.

Furthermore, the flawed premise of the show — and incidentally of much of the American ғconversation about race — is the idea that racism can be vanquished by the talking cure. It would be lovely to think that if whites and blacks sat in a circle and shared their feelings, and purged and validated and tap-danced for two miles in each otherԒs moccasins, we could put aside all the sticky confusions of who can say what and who gets to say the N-word and how it should be spelled and whether Ebonics is a valid dialect and why the NFL has so few black quarterbacks, and just reach out for a big multi-hued group hug.

But even the desire for that group hug, which underscores the whole reality experimentӔ of Black.White.Ӕ is a kind of bad faith — our way of hiding from the very uncomfortable truth that we cant get rid of racial conflict without dismantling the institutions that help perpetuate it. Skin color per se is not the primary mover of racial strife in 2006. Rather, itҒs the fact that so many of the people who happen to have black skin are also desperately poor, and for plenty of complex and not particularly TV-friendly reasons: a devastating historical legacy; failing educational systems; welfare reform; measures like the Rockefeller Drug Laws (which have done more to destroy black families than anything else since slave days); the list goes on and on. But very few Americans, particularly the havesӔ of all races, colors and creeds, are interested in making the sacrifices necessary to tackle that list, let alone watch a serious treatment of them in prime time. No amount of empathetic listening and emotional catharsis is going to change that.

Dont we wish it would though? Then we could enjoy our lattes and our tax breaks too. ғBlack.White. speaks to that wish, reassuring us that our troubles could be resolved if only weԒd all just listen to each other a bit better. The series amuses, instructs, frequently embarrasses — but it never really challenges, because its two families have one thing that may well bind them together more effectively than race could ever pull them apart: They have some money.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.