|

To see long excerpts from “Fourth of July Creek” at Google Books, click here.

|

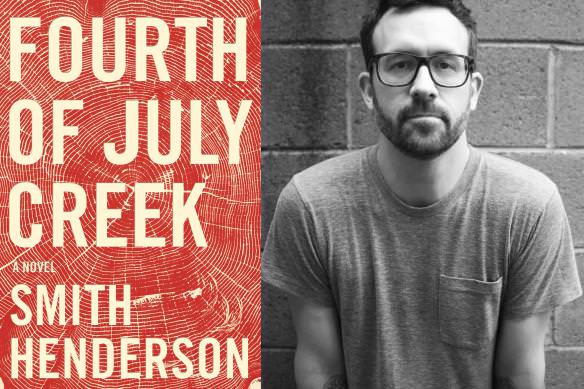

“Fourth of July Creek”

A book by Smith Henderson

If you fly in the rarefied air of literary awards, you may have caught Smith Henderson’s name a few years ago when he won a Pushcart Prize and a PEN Emerging Writers Award. A 41-year-old advertising writer originally from Montana, Henderson has published a few stories in literary magazines that, like exotic birds, are known to exist but are rarely spotted.

Those days of obscurity are over. His first novel, “Fourth of July Creek,” is the best book I’ve read so far this year. On a gamble that seems sure to pay off, his publisher is releasing 100,000 copies, and he’s working on a TV adaptation. The product of more than a decade’s work, this richly plotted novel is another sign, if any were needed, that new fiction writers are still telling vibrant, essential stories about the American experience.

In so many ways, the story Henderson tells here describes an American experience most of us never have to see — but should. Far from big cities or either coast, his characters are the poor and working poor in sparsely populated towns that few escape and no one ever moves to. For these people, who spend every cent they earn, a layoff, an illness, even a car-repair bill can collapse a whole family, and the ones most violently upended by those misfortunes are children.

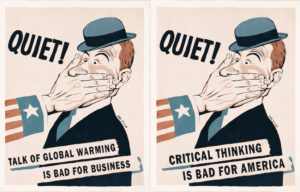

Pete Snow, the protagonist of “Fourth of July Creek,” knows such children well. A social worker in Montana in the early 1980s, he belongs to that class of municipal servants who show up as the police handcuff a raging father or the medics zip Mom’s needle-marked body into a bag. While the sheriff carries a gun, Pete wields his clipboard. Armed only with free diapers and soup cans, he stares down proud, angry parents who are contemptuous of big government but hungry for government aid. Dazed by the infinite creativity of sexual abuse but blessed with the dexterity of hope, he keeps struggling to make damaged families work. One day he has to remind a young mother that her baby can’t feed itself; another day, he’s got to convince a faithful man that sin didn’t poison his wife. And none of this often-futile work takes place on anything like a predictable schedule: The law may dawdle for months over what to do with an addict, but her little girl needs a safe place to sleep tonight.

The social worker is a tempting figure to beatify, and God knows these low-paid, overburdened people deserve all the veneration we can give them. But Henderson, who once worked at a group home for juveniles, is too fine a writer to set a wooden saint at the center of his novel. Instead, he gives us a flawed and wounded hero. Pete may save others, but he can’t hold his own family together. He’s left his adulterous wife and bitter teenage daughter and now lives in a cabin without electricity; he showers at the courthouse. When his no-good brother appeals for help, Pete tells him, “Will you just get back in your truck and go?” The endless labor of patching up desperate strangers provides a comforting way to ignore his own derelict life. As he drunkenly admits one night to his wife, “I take kids away from people like us.”

Like those other ad-men-turned-novelists Peter Carey and Salman Rushdie, Henderson knows how to create the sensation that we’re being propelled through a story that’s just as poignant as it is frightening. Infused with psychological complexity and lush with the landscape of the Northwest, the novel barrels along with the chaotic demands of Pete’s job and family, from crisis to crisis to quiet scenes of despair. At unexpected moments, the narration shifts briefly into the second person, placing us right in Pete’s life. And that larger story is interrupted by snippets of dialogue between two unnamed figures talking about the harrowing plight of Pete’s daughter. It’s a complex structure that could easily grow unwieldy, but Henderson choreographs these parts so masterfully that the novel is never less than wholly engaging.

Pete’s most challenging case, which becomes the story’s focus, involves a scurvy 11-year-old boy who wanders up to a school playground and speaks “in the clipped cadence of a POW, announcing at one point that he’d renounced his citizenship.” Returning the boy to his home in the forest, Pete meets the boy’s dad, a survivalist named Jeremiah Pearl. And so begins a perilous relationship between these two troubled fathers, each trying to save his own child from the evils of the world.

Pearl — “Tribulation-ready, Race War-ready” — seems at first a spooky Gothic creature, slipping silently through the woods, spending coins with holes punched in the presidents’ heads. But illuminated by Henderson’s sympathy, this tortured zealot becomes both victim and villain, an endlessly fascinating character caught in the confluence of personal tragedy and America’s darkest fears. Here is the millennial complex in full bloom, the craziest, most poisonous expression of anti-government paranoia fueled by a corrupted brand of Christianity. Obsessed with tangled biblical prophecies, Pearl announces, “I am dynamite” and hunkers down with his guns and his gold. The last thing he’ll accept is some godless social worker trying to tempt his children with the Devil’s medicine.

But Pete is determined to serve families wherever they are, no matter how loopy they may seem. And in a similar way, this novel is engaged in the hard work of understanding people we usually write off in disgust. Pursued by the four horsemen of ignorance, poverty, drugs and illness, who wouldn’t think the Apocalypse is nigh? As Pete’s personal life spirals out of control, Pearl’s radical break from civilization offers an alluring kind of solace, a relief from his complicated failings. But can Pete win the anarchist’s trust before he sparks a deadly confrontation with government officials, who suffer from their own brand of paranoia?

All week I was looking for opportunities to slip back into these pages and follow the trials of this rural social worker. The greatness of “Fourth of July Creek” stems from Henderson’s ability to subtly tie the struggles of one ordinary man to the broader currents of American culture, both its blessings and its evils. The result is a story that is simultaneously intimate and grand, written in a style athletic enough to capture a spectacular range of harrowing events. These may be the End Times for Jeremiah Pearl, but they’re just the beginning for Smith Henderson.

Ron Charles is the deputy editor of The Washington Post Book World.

©2014, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.