Forced Marriage of Children Happens in America, Too

Between 2009 and 2011, at least 3,000 girls and young women from 47 states were forced into marriage—including many under the age of 18.

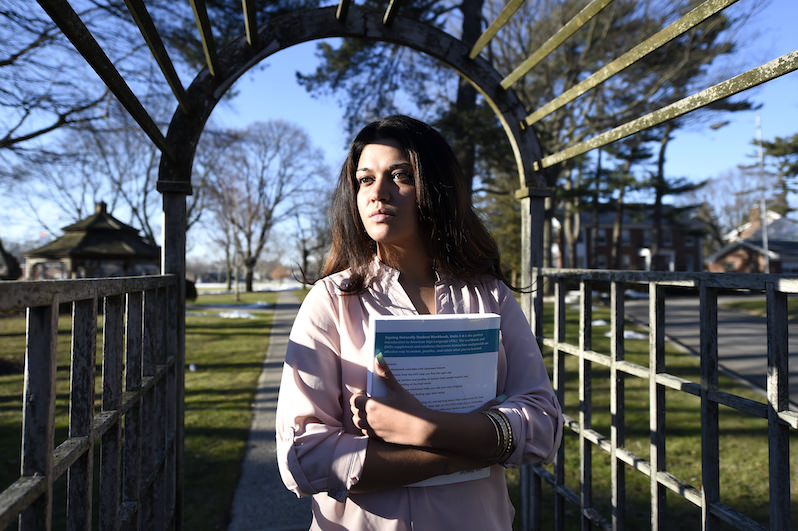

Child bride Naila Amin at Nassau Community College in Garden City, N.Y., early last year. (Kathy Kmonicek / AP)

Naila Amin appeared to have an ordinary American childhood. She lived in a middle-class house on Long Island, New York. Her parents doted on her. None of her teachers or neighbors could have guessed that she had been betrothed to a man since age 8.

At 13, Amin was forced to marry the then 26-year-old man during a family trip to Pakistan. She returned to middle school in New York afterward. She did not take the marriage seriously. Her American life carried on as usual. She pierced her nose. She started dating in high school.

Her parents disapproved of her behavior. When she was 15, they moved with her to Pakistan, where her husband raped her night after night. She tried to swallow bleach, although she couldn’t bring herself to drink enough of the pungent liquid to die.

“It was unbearable,” Amin told me. “I cooked for my enemy, cleaned for my enemy, slept next to my enemy.”

Her husband confiscated her cellphone and passport. Amin convinced an uncle to call U.S. Child Protective Services (CPS) on her behalf, but it was too late. U.S. authorities could not intervene in a marriage deemed legal in another country.

Such marriages take place more often than one might think. Forced marriages are not uncommon for American girls as young as 4, although on average these girls and women are between 14 and 25 when they marry.

Between 2009 and 2011, at least 3,000 girls and young women from 47 U.S. states were forced into marriage—including many under the age of 18. The data come from a survey conducted by the Tahirih Justice Center, a nongovernmental organization that provides pro bono legal services for abused immigrant women and girls in the United States.

Minors attempting to escape from forced marriages have fewer options than adults. Most women’s shelters do not take in girls under the age of 18. For those that do, CPS or legal guardians are called after 24 hours.

Amin is now 26. She recently launched the Naila Amin Foundation, dedicated to creating the first shelter in the U.S. to protect underage American girls from child marriages and honor killings.

Amin is a rare child marriage survivor who escaped captivity and eventually returned to the U.S. This was thanks to the fact that, before the final trip to Pakistan, Amin had briefly entered foster care because her parents had beaten her severely for dating in high school.

Despite that, in foster care, she missed home. She felt sick with sadness when her mother visited the group home on Saturdays to bring a week’s worth of home-cooked halal food. She felt stripped of her Muslim identity. She ran away and returned to her parents’ house.

At age 14, Amin stopped going to school and lived covertly at home. CPS workers made weekly surprise visits, but Amin hid in the closet during the inspections.

Five months after she and her family moved to Pakistan, Amin’s parents returned to the United States. Because her uncle had called CPS, Amin’s mother was arrested upon her return and charged with kidnapping.

Her father had no choice but to ask Amin’s husband to allow Amin to return to the United States.

Honor violence is all too familiar to Amin.

Before her parents’ return to the U.S. she had tried to run away from her husband’s house in Pakistan. Hearing that Amin was gone, her father reached for his gun, clutching it tight as he waited for male relatives to catch her.

The men caught Amin and forced her to return to her husband. To protect Amin’s life, other family members locked her father in the house for days. They hoped he would put away his gun. He eventually did.

Many are not as lucky. Most girls at risk of a child marriage or honor killing in the U.S. do not come to the attention of CPS or other social service agencies.

In 2009, when 20-year-old Noor Almaleki, an Iraqi-American, rejected an arranged marriage in Arizona, her father struck and killed her with his car.

In 2008, Yaser Said shot his two teenage daughters in the back of his taxicab in Texas. He killed one for having a boyfriend and the other for rejecting an arranged marriage to an older man in Egypt.

Sixty-seven percent of the girls and young women surveyed by the Tahirih Justice Center said their issues had not been identified as problems by local agencies.

Forced marriages are a culturally sensitive and complex issue that most government agencies—such as women’s shelters, CPS and local law enforcement agencies—are not equipped to handle.

The typical signs of child abuse—physical injuries, frequent absences from school and malnourishment—often don’t come into the equation.

CPS does not view impending child marriages as abuse. It cannot take action until abuse has occurred. And most of the time, CPS can’t intervene when an American girl is forced into marriage overseas.

But not all child marriages take place overseas. Many occur on American soil.In New York and most other states, a girl as young as 16 can marry if she has parental consent. The age minimum is even lower in some states — in Massachusetts it’s 12. In California, age is immaterial if there is parental consent, and consent of the child is not required.

Unchained at Last, a nonprofit group that helps women and girls avoid forced marriages, found that 3,481 children were married in New Jersey between 1995 and 2012. Most were age 16 or 17, but 163 were between 13 and 15.

Approximately 91 percent of the children were married to adults. Many of these marriages involved age differences that could have resulted in statutory-rape charges had the participants not been married.

In the United States, girls and young women from various ethnic and religious backgrounds—most frequently Pakistani, Afghan, Indian and Somali—are forced into marriage. Their religions may be Muslim, Orthodox Jewish, Christian or no religious affiliation.

The IRS approved Amin’s foundation as an official nonprofit in October. She is raising funds and plans to have a shelter up and running in six months.

Amin’s shelter will arrange transportation for girls who seek help. They will receive physical and psychiatric evaluations once they arrive.

“We need to see what their mental state is,” said Amin, who has unique insight into the successes and failures of social service agencies when it comes to addressing child marriages in the U.S. “We don’t know what they’ve been through up to this point.”

The girls will meet with social workers once a week. They will continue their education and receive vocational training. They will also have access to meditation therapy and other support services.

“We’ll have halal food for Muslim girls. We’ll have a prayer room if they want to pray. If they’re Christian, we’ll have another prayer room. They can practice whatever they want to practice,” Amin says. “I won’t take their culture or identity away from them.”

“You want to wear a hijab, you wear it. You want to wear booty shorts, go ahead. I want them to feel at home,” Amin said. “What I didn’t have is what they’ll have.”

Girls and young women are forced into marriage for reasons including security, companionship and the preservation of a family’s reputation.

Sometimes it’s a way of stopping behaviors that the family disapproves of, such as dating outside of the family’s culture or religion.

Arranged marriages are not necessarily bad. They can turn into healthy relationships if there is mutual consent. But forced marriages—especially when they are forced on a very young girl—can to lead to domestic violence, early pregnancies and higher risks of maternal mortality. They also negatively affect health, education and economic opportunities for the girls.

In the last two years, four states—New York, New Jersey, Virginia and Maryland—have introduced legislation to remove or limit early marriage exceptions. Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe has so far been the only one to sign such a bill into law.

Meanwhile, there is a dire need for a safe space for children at risk of forced marriages or honor violence. Amin receives 40 calls and social media messages a week from underage girls who are trying to avoid an early marriage.

“It happens every single day in the U.S.,” Amin said. “People just don’t know about it.”

“I spoke to a lot of girls. Their biggest fear is, ‘Where are we going to go?’ ” Amin said. “What’s keeping these girls from getting help is fear of an uncertain future.”

To this day there is a scar on Amin’s left thigh where her ex-husband repeatedly kicked her. It reminds her of the urgency of the work that lies ahead.

“I really want this to work, from the bottom of my heart, so no one has to go through this alone like I did,” Amin said. “Underage girls, we’ve got your back. We have to move away from old traditions. There is hope.”

Amelia Pang is an award-winning journalist, formerly with the Epoch Times.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.