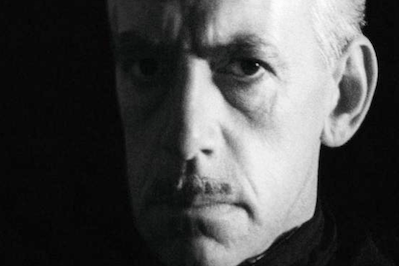

Eugene O’Neill: A Life in Four Acts

A new biography reclaims the playwright of "A Long Day's Journey Into Night" as a self-conscious, committed artist who strove to break through the limits of production and consistently voice his lifelong contempt for American materialism, imperialism, racism and puritanism. Photo by Yale University Press

Photo by Yale University Press

Photo by Yale University Press

|

To see long excerpts from “Eugene O’Neill” at Google Books, click here. |

“Eugene O’Neill: A Life in Four Acts” A book by Robert M. Dowling

Robert M. Dowling’s thoughtful book restores balance to the slightly skewed 21st-century reputation of America’s greatest playwright. The ubiquity on world stages of Eugene O’Neill’s three crowning achievements — “The Iceman Cometh,” “Long Day’s Journey into Night” and “A Moon for the Misbegotten” — has led to a narrow perception of him as the grimly naturalistic purveyor of a desolate worldview formed by his horrific family history. These late-career masterpieces have overshadowed the many groundbreaking works that preceded them, fostering the notion that O’Neill was exclusively concerned with his internal drama.

On the contrary, Dowling reminds us, O’Neill’s plays consistently voice his lifelong contempt for American materialism, imperialism, racism and puritanism. His empathy for the oppressed and outcast is evident in the seafaring dramas that first made his reputation in 1916-1917. He believed audiences wanted more than trivial, phony entertainment, and he was proved right in the years between the two world wars, when his innovations in theatrical form and content gave him a string of unexpected hits. Dowling selectively highlights key moments that demonstrate the playwright’s “ripple effect … on American theater and culture,” dividing his narrative into four “acts” linking O’Neill’s experiences with historic shifts in American theater.

The first act depicts a childhood shadowed by his mother’s drug addiction and his father’s perpetual touring in “The Count of Monte Cristo,” a profitable, artistically negligible melodrama. Dowling sensibly relies on Louis Sheaffer’s pioneering research in “O’Neill: Son and Playwright” (1968) and “O’Neill: Son and Artist” (1973) for most biographical facts. But while Sheaffer sees O’Neill’s relationship with his parents as central to his life and work, Dowling contends that O’Neill’s turn to playwriting was part of the process of “abandoning the child-self that had possessed him for too long.”

In the book’s second part, Dowling spotlights O’Neill’s collaboration with the Provincetown Players, a Greenwich Village group that shared his desire to smash outworn theatrical conventions. The playwright had two successful Broadway productions during this period (“Beyond the Horizon” in 1920 and “Anna Christie” in 1921), but Dowling focuses on his downtown experiments with effects such as the use of colored lights and beating drums. He argues persuasively that O’Neill primarily was interested in discovering new ways to move and challenge audiences. His explorations were triumphantly justified in 1920 by “The Emperor Jones,” the first popular American play to make use of European expressionist techniques (such as symbolic scenes and sound effects to portray emotional states) and to star an African-American actor supported by a white company.

O’Neill continued to mingle theatrical and social provocation in his productions of the 1920s and early ’30s, refusing to bowdlerize his material to suit contemporary prejudices or commercial imperatives. He didn’t have to, Dowling demonstrates in the third part of the book, which follows O’Neill from the Village to the Broadway theater as it succumbed to the revolution he and his comrades had wrought in the little theater movement.

The downtown shows were radical. “The Hairy Ape” (1922) dramatized working-class rage. “All God’s Chillun Got Wings” (1924) portrayed an interracial marriage. “Desire Under the Elms” (1924) made brilliant use of symbolist scenery and lighting to make palpable the play’s themes, but critics noticed only its sexual frankness, which led to censorship battles across the country. “The Great God Brown” employed the ancient device of masked actors to illuminate contemporary psychological conflicts.

O’Neill’s Broadway productions were just as radical. “Strange Interlude” (1928) aimed for the freedom of a novel, voicing its characters’ private thoughts in a new kind of soliloquy. “Marco Millions” (1928) satirized Marco Polo as a Babbitt-like businessman interested only in making money. “Mourning Becomes Electra” (1931) created an American equivalent for Greek tragedy by relocating the Oresteia to Civil War-era New England. All were box-office successes. O’Neill had forced the commercial theater to accept him on his own terms. The Nobel Prize in 1936 capped the decades of his greatest celebrity and influence.

In the last section of the book, Dowling takes us from that high point through the dark years of declining health that made it impossible for O’Neill to write after 1943. “The Iceman Cometh,” which received mixed reviews in 1946, and “A Moon for the Misbegotten,” which closed out of town in 1947, were the last plays produced while he was alive. O’Neill destroyed the incomplete manuscripts of his 11-play cycle about the dire spiritual consequences of Americans’ lust for success. He forbade publication of the nakedly autobiographical “Long Day’s Journey into Night” until 25 years after his death, which came in 1953.

Dowling covers this bleak period briefly. Although he serviceably relates the major events in O’Neill’s life, including his three marriages and struggle with alcoholism, readers looking for a comprehensive biography would do better with Sheaffer’s two volumes. What makes this book a valuable complement to them is Dowling’s emphasis on the playwright’s engagement with the world and the theater.

Glib journalists often condescend to O’Neill as someone who spewed forth his personal demons in badly written plays that occasionally turned out to be great almost by accident. Dowling reclaims him as a self-conscious, committed artist who strove to break through the limits of production and get as much of the human condition onstage as possible. The freedom he seized and bequeathed to subsequent playwrights — from Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams to Tony Kushner and Sarah Ruhl — transformed the American theater. Compelling though his tragic personal story is, that is the more important story, perceptively recounted in “Eugene O’Neill: A Life in Four Acts.”

Wendy Smith is a writer in New York who frequently reviews books for The Washington Post.

©2014, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.