Emmett Till: Confronting White Supremacy

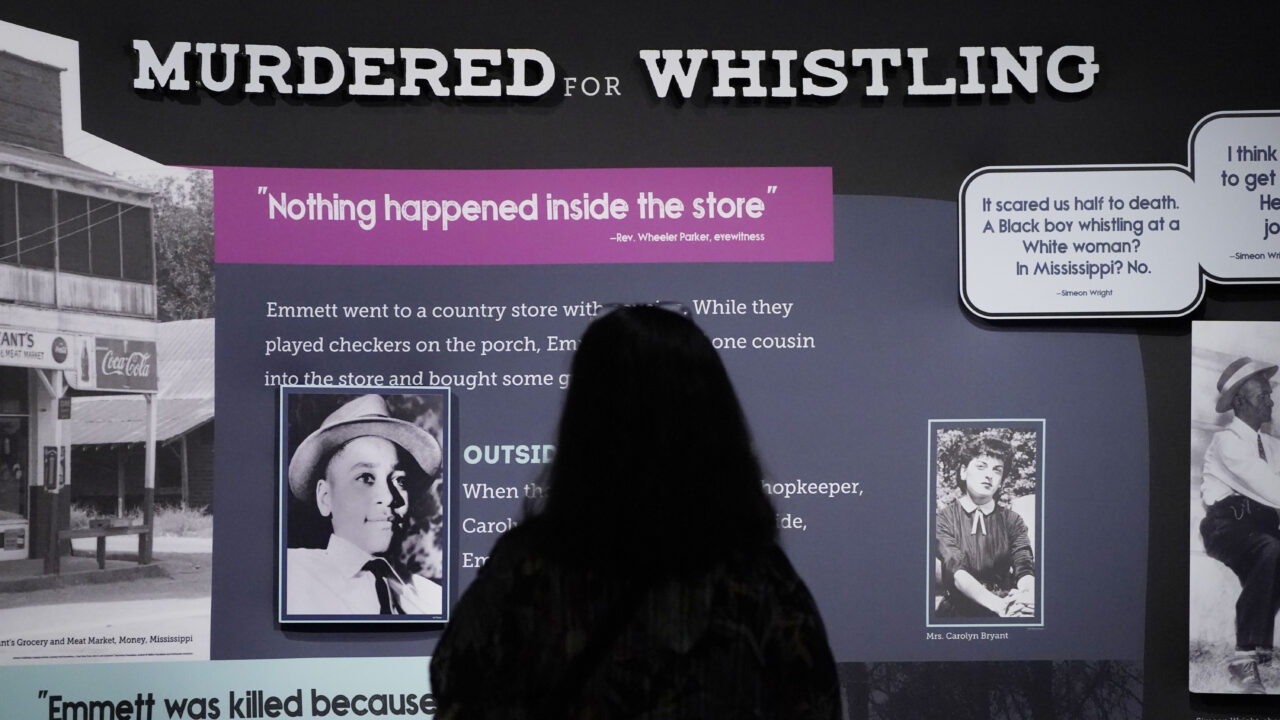

A shocking picture provided clarity on grotesque fear. Lotte Dula of Denver, Colo., examines a panel of the "Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley Let The World See" exhibit with photographs of a young Till, left, and a photograph of Carolyn Bryant, the white woman who accused the teenager of making improper advances before he was lynched in Mississippi in 1955, Thursday, April 27, 2023, at the Two Mississippi Museums in Jackson, Miss. Carolyn Bryant Donham died Tuesday, April 25 in hospice care in Louisiana. She was 88. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Lotte Dula of Denver, Colo., examines a panel of the "Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley Let The World See" exhibit with photographs of a young Till, left, and a photograph of Carolyn Bryant, the white woman who accused the teenager of making improper advances before he was lynched in Mississippi in 1955, Thursday, April 27, 2023, at the Two Mississippi Museums in Jackson, Miss. Carolyn Bryant Donham died Tuesday, April 25 in hospice care in Louisiana. She was 88. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

By seventh grade, I had heard of “white supremacy,” but I didn’t understand what it meant. Seeing a picture of 14-year-old Emmett Till’s open casket in our bathroom copy of Jet magazine provided some clarity. The face of the McCosh Elementary School seventh-grader had been beaten and disfigured into a grotesque mashup of broken Black flesh and American history. Beaten and disfigured by white supremacy.

That’s how I met Emmett Till. Bobo to his friends. I stared at the picture. He was wearing an unbuttoned black suit jacket and crisp white shirt, his Sunday best. Bobo should have been going to Easter service, —not his own funeral service. I remember being afraid.

Fear is the engine of white supremacy.

Seeing a picture of 14-year-old Emmett Till’s open casket in our bathroom copy of Jet magazine provided some clarity.

When Roy Bryant and his half brother John Milam armed themselves and knocked on Till’s great-uncle Mose Wright’s door after 1 a.m on August 28, 1955, they knew fear would make Wright hand over his nephew. Wright, 64 at the time, had been raised in the culture of fear that defined Mississippi’s race relations. It was fear rooted in a gun like the pistol Milam held when he said through the screen door, “I want that boy that done the talking down at Money.”

Two white domestic terrorists — joined by blood — had come for Wright’s Black kinfolk.

The talking done at Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market down the road in Money, Mississippi, was the reason for the pistol. There was some dispute about the specifics of the talking done to Carolyn Bryant, Roy Bryant’s 21-year-old wife. She testified (and later recanted) that Emmett Till grabbed her wrist and asked her for a date. Till’s cousin, eyewitness Simeon Wright, refutes that and said Till whistled toward Carolyn Bryant when she walked out to her car.

The Ku Klux Klan was part of the region’s daily life. In the white supremacist code, whistling could be capital crime — especially for a Black male child whistling at a white woman. There was no need to write this code down. The whistle rule was written in fear on Black hearts and minds — including Wright, who was terrified by Bobo’s whistle.

“You know, we were almost in shock,” Wright said “We couldn’t get out of there fast enough, because we had never heard of anything like that before. A Black boy whistling at a white woman? In Mississippi? No.”

Fear backed by white violence is a mean teacher. Wright had learned this tough lesson. His cousin would learn it on a much deeper level.

In September 1955, Roy Bryant and Milam were brought to trial at the Tallahatchie County Courthouse. In Tallahatchie County, 63 percent of residents were Black. Under Mississippi state law, only registered voters qualified as jurors. At the time of jury selection, the state’s aggressive voter suppression and voter intimidation had resulted in no Black registered voters in Tallahatchie County.

On September 23, 1955, an all-white jury acquitted Roy Bryant and Milam in the murder of Till.

After deliberating for only 67 minutes.

In the white supremacist code, whistling could be capital crime — especially for a Black male child whistling at a white woman.

Protected by double jeopardy prohibition, Bryant and Milam confessed to Till’s murder in the January 1956 edition of Look Magazine. While justifying the seventh grader’s killing, Milam said, “Well, what else could we do? He was hopeless. I’m no bully; I never hurt a nigger in my life. I like niggers — in their place — I know how to work ’em. But I just decided it was time a few people got put on notice. As long as I live and can do anything about it, niggers are gonna stay in their place. Niggers ain’t gonna vote where I live. If they did, they’d control the government. They ain’t gonna go to school with my kids. And when a nigger gets close to mentioning sex with a white woman, he’s tired o’ livin’. I’m likely to kill him.”

John Milam was white supremacy’s trigger man.

And the state gave Milam cover. It gave Roy and Carolyn Bryant cover. It protected them so they could live long lives. Carolyn Bryant Donham died April 25, 2023. Of natural causes.

She lived to be 88.

Seventy-four more years than Emmett Till.

Historian Dexter Blackman told Truthdig, “One lesson from the Emmett Till case and its long aftermath is that the state protects white supremacy. The state ensured an all-white jury to protect white supremacy. The state protected Emmett Till’s white supremacist murderers. The state protected white supremacist accuser Carolyn Bryant so she was able to live a long life. But the state doesn’t protect Black life. The state didn’t protect Emmett Till.”

America should protect seventh graders.

I don’t recall having this thought as I stared into an open Jet magazine that showed Bobo’s open casket. Showed his Sunday best. His seventh-grade face disfigured by a mean teacher named white supremacy. I do recall feeling afraid. Very afraid.

I was in seventh grade, too.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

"the state gave Milam cover. It gave Roy and Carolyn Bryant cover. It protected them so they could live long lives. Carolyn Bryant Donham died April 25, 2023. Of natural causes. She lived to be 88."

I would say that it's not just "the state" that protects white supremacy, but rather a universal system led by, and started by Christianity, when Catholic Popes memorialized Papal Bulls instructing white Europeans to go around the world stealing...

"the state gave Milam cover. It gave Roy and Carolyn Bryant cover. It protected them so they could live long lives. Carolyn Bryant Donham died April 25, 2023. Of natural causes. She lived to be 88."

I would say that it's not just "the state" that protects white supremacy, but rather a universal system led by, and started by Christianity, when Catholic Popes memorialized Papal Bulls instructing white Europeans to go around the world stealing and controlling black lives and their properties, all in the name of God.

Now that black domination and degradation have long been embedded, encoded and defaulted in the DNA and therefore the collective consciousness of black people, there's no hope for overcoming, unless black people are courageous enough to release the collective fear, that also exist collectively in those who believe in and practice white supremacy and all of the other lies and nonsense, that justifies and permits group crimes against other members of the human race.

Fear from black people of white people and fear from white people that black people must collectively have a constant desire to do unto them as they've historically done unto us,

are equal co-conspirators in maintaining and weaponizing the power that white supremacy still holds.

Continued failure of too many to realize that white supremacy is a worldwide disease, originated from the diseased minds of ungodly Christians, will allow white supremacy to

continue unabated and only morphing in character forever more. No matter how much we march, say thank you Jesus, hallelujah or win a few cases in courts, white supremacy will remain the dominant default worldwide awareness, to which we all adhere to some degree, no matter the color of our skins.