Ellen Goodman: Some Things Do Not Pass

My mother died last month at 92. At the end, she had lost much of what she had. But, still, she left treasures.BOSTON — Long, long ago, I wrote a column describing my mother this way: “My mother is someone who will listen to your problems until you are bored with them.”

Reader’s Digest wanted to use it, and a fact-checker called me for my mother’s telephone number. She actually wanted to ask my mother whether it was true.

I told this tale for years as a funny story about fact-checkers. But now, of course, I know it was really a story about my mother. About Edith Weinstein Holtz, who died last month at age 92, just two days after Thanksgiving, on what would have been the 70th anniversary of her wedding.

It had been a long, long time since my mother was able to listen to my problems. Dementia, that terrible thief, stole her memory and then her personality, one piece at a time. Obituaries rarely list dementia as a cause of death. But she was a victim of its burglary until, at last, she let go of food, of fear, of need, of life.

My mother, born before suffrage, before World War I and World War II, before the feminine mystique and feminism, taught me everything I know of family values.

She taught me that family came first. She taught me to make cheesecake and keep peace. She taught me that a real home was a place where you were welcome for Sunday brunch and conversation. She taught me to accept your children’s life choices without criticism and with confidence in their judgment. She taught me patience — although I am afraid I never passed the finals in that class.

When my sister and I went to the funeral home, the director asked us how to list her occupation. Together, we said, “homemaker.” Making a home was all she ever wanted to do. My mother, beautiful and vulnerable, also taught us — not on purpose — the risk of having love as your only job.

When my father died, she was only 50. She didn’t worry about how to live without this vital, funny, loving center of her life because, I found out later, she didn’t think she would survive a year. She lived 42 more years.

I think my mother regarded “independence” as a synonym for “loneliness.” She tried to create a second life. She tried school. She tried a job or two. She tried another marriage. Nothing really worked. But over these years she was also the one who nourished her granddaughters and nephews with peppermints and attention. She listened to their problems until they were bored with them.

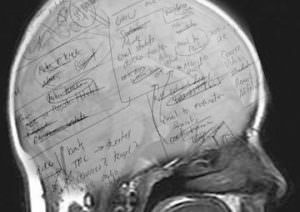

Old age is not for sissies. My mother’s long slow terrible decline lasted over a decade. There was the television she could no longer work and then the telephone. There were the small spiral notebooks whose pages were covered with names from a past she struggled to retain. One page listed her favorite movie star: Cary Grant. Another listed my father’s best friend: Lou Novins.

In the last year, what mattered to my mother? The $3 faux pearl stud earrings, final artifacts of her femininity, bought by the dozen and lost by the dozen. The boxes of chocolate and the family photos. My mother never lost the taste for chocolate, nor did she lose the smile with which she welcomed her family.

We were gathered for Thanksgiving weekend when she died. That would have mattered to her. It mattered to us. Together, we were able to rewind the tape to the days when our mother, aunt, grandmother, sister was our listener.

There is little that is harder in life than watching the slow disappearance of someone you love. Dementia is a contagious disease that spreads its suffering to anyone within the range of love. Millions of families have caught it. Ours is just one. And yet here, too, she taught us more than simply how to bear a burden.

Not long before her death, my daughter and I took my 3-year-old grandson to visit. We outfitted him with a bag of doughnuts to pass out to my mother and everyone on her floor. Though she no longer knew his name, she watched him with joy.

The next morning at a breakfast table covered with cereal and Play-Doh, he looked up and asked me, “Grandma, is your mommy going to die soon?”

Taken aback, I answered, “I’m afraid she is, Logan.” He thought for a moment and said, “But, Grandma, then you won’t have any mommy.”

After the silence filled only with my tears, this little, little boy turned and said, “Grandma, when I grow up, I’ll be your daddy.”

So my mother’s gift for family, my mother’s talent for empathy, was passed down from one generation to the next and the next. It is her abiding legacy.

Ellen Goodman’s e-mail address is ellengoodman(at symbol)globe.com.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.