Education: Poverty Is the Crux of the Problem

If income divide is at the root of current public education deficits, that chasm must be narrowed by reducing the factors that perpetuate poverty.

By Paul Cummins and Ray Reisler

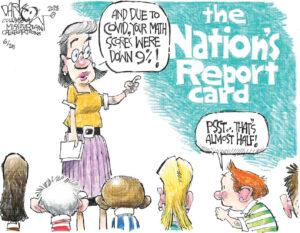

In the past few months, news articles have suggested that the data on achievement gaps among public school students is puzzling and that when it comes to solutions, “the cupboard is bare.”

Nothing could be further from the truth.

As demonstrated in the work of Linda Darling-Hammond, an education professor at Stanford University, and Diane Ravitch, an educational policy analyst and research professor at NYU, there are a plethora of social and educational tools that are evidenced-based, successful and available. The problem, from our perspective, is insufficient will and funding to take these proven practices to scale. We contend that there is a critical need at state and local levels for additional financial investment in K-12 education, as well as sustaining contributions from the private and philanthropic sectors. To accomplish this goal requires an acknowledgement that federal and state tax policies have failed and that there has been inadequate regulation of financial and investment behavior.

Looking over some media reports, it might appear that the data does not support the common assumptions that ascribe “race variables” for the existing achievement divide between white and minority students. Indeed, a Stanford researcher’s recent study of standardized test data reveals a 40 percent growth in the gap between high- and low-income students since the 1960s.

However, what the research does not address is what percentage of these economically poor students are minorities. The reality is that the proportion of poor minorities is greater than that of poor whites. For example, when we look at low-performing inner city schools compared with high-performing affluent suburban or high-income urban campuses, the racial and income divides are “invariably” one and the same. There are, of course, exceptional schools in low-income neighborhoods, but they are just that — exceptional. That these campuses are exceptions does not negate the extant, persuasive correlations and associations among race, income, achievement and budgetary resources; rather, they simply demonstrate that there will always be exceptions for myriad reasons, and most often not replicable.

As we indicated earlier, the cupboard for closing the achievement gap is far from bare. Successful, evidence-based programs and tried-and-true practices are flourishing in disparate neighborhoods and school settings. Teaching and race are essential variables, but poverty is the crux of the challenge that must be faced. If income divide is at the root of current public education deficits, that chasm must be narrowed by reducing the factors that perpetuate poverty. What is lacking among many of the nation’s mayors, county executives and state leaders as well as the board members of its 16,000 school districts is a willingness to design and execute an all-out assault on the calamitous growing inequality that has been institutionalizing and increasing poverty while ravaging educational opportunities.

Regrettably, some pundits and researchers will twist the income divide data into an argument that income inequality is “more of a symptom than a cause.” This ad hominem approach highlights a symptom caused by “culture” and the absence of appropriate social conditioning among poor people. Educated people, they point out, marry other educated people, thereby providing better learning conditions for their children. Furthermore, they argue, educated people produce fewer children out of wedlock than poor people do and don’t have as many health, housing and employment challenges. The list goes on. Just change the cultural and social conditioning of poor people and they will achieve as well as the college educated.

Sounds like a “free lunch” to us!

This, of course, raises the question of how poor people, whose children attend schools that are underfunded, are supposed to transform their “culture” and increase their kids’ chances of educational success. Educational deprivation has everything to do with enough money to fund programs and practices that have proven their effectiveness. The Los Angeles Unified School District, for example, now spends approximately $7,500 per pupil, with some smaller poorer districts spending around $5,000. Private schools spend $30,000 to $35,000 per pupil. At this financial level, the “culture of learning” is enriched, diverse and comprehensive.

Guess which schools and whose families provide the better culture and accompanying social conditioning? Guess which families inject less trauma in their children’s lives and which kids suffer fewer physical and emotional health consequences from that trauma? Guess which families have a better chance of remedying the physical and emotional health consequences of deprivation? Guess which children are more physically and emotionally ready and able each morning to sit in a classroom and achieve at expected levels?

The answers to these questions are etched on the faces of myriad school guidance counselors and teachers. The stories of some of these poverty-impacted children and the resulting educational fallout are eloquently documented by Paul Tough in a New Yorker magazine article from March 2011 titled “The Poverty Clinic.”

So when commentators say it isn’t an issue of money, we say nonsense! It’s nearly impossible to improve the increasingly undernourished public school curricula and staff levels — the result of budget cuts — without funding. Similarly, when it comes to health, we believe that emotional and physical well-being is inextricably tied to educational readiness. It’s daunting, to say the least, when emotional and economic barriers obstruct the pathway to success.

The growing income divide is largely still a racial one. Although the solutions to both gaps are social and educational, they are also inherently economic. What is needed is adequate funding that would underwrite targeted interventions to compensate for the inequities that have prevented poor children from receiving an appropriate education. To correct the lack of funding would require a revision in our attitudes and practices regarding taxation and financial regulations. As Joseph Stiglitz points out in his recent book “The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers our Future,” federal and state governments must invoke more progressive taxation with greater attention to capital gains taxes; drastically tighten laws governing bankruptcy, corporate executives’ pay and anti-trust; and bolster regulations monitoring the financial industry. Unabashed commitment and progress in these areas would move mountains in unleashing the power of equal education opportunity while also narrowing the income and achievement chasms that have slowed the U.S. potential for economic growth. The regulatory and macroeconomic changes advocated here are requisite for creating conditions that will spark improved educational performance by those most at risk of failure.

There’s also another major factor at work here: The ongoing cuts to public services, such as nutrition, health care, food stamps, Head Start and other “zero to 5” programs as well as subsidized housing for the homeless and disabled, have all inflicted pain that is startling and personal. The impact on educational performance in public schools is severe.

The gap between wealth and opportunity is now at crisis levels. The rich and the ultrarich may remain so, but both will have to do with less if we, as a society, wish to halt the widening of the gulf. We can do so by redistributing money along some rational, sane and fair lines. It’s time to acknowledge in the public dialogue over educational achievement that we need to fund poor children as robustly as we fund rich ones.

Paul Cummins is the president of New Visions, an organization in Los Angeles that provides innovative educational opportunities to underserved youth. Ray Reisler served as the executive director of the S. Mark Taper Foundation in Los Angeles for 21 years.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.