Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and the Future of the Death Penalty on Trial

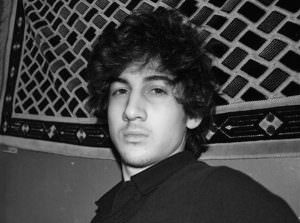

In a very real way, the future of the death penalty -- a barbaric relic of a bygone era abolished by more than two-thirds of the world’s nations -- will also be on trial with the suspected Boston Marathon bomber.In a very real way, the future of the death penalty—a barbaric relic of a bygone era abolished by more than two-thirds of the world’s nations—will also be on trial with the suspected Boston Marathon bomber. Boston Marathon bombing suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, bloody and disheveled with the red dot of a rifle laser sight on his forehead, raises his hand from inside a boat at the time of his capture by law enforcement authorities in Watertown, Mass., on April 19, 2013. (AP Photo/Massachusetts State Police, Sean Murphy, File)

Boston Marathon bombing suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, bloody and disheveled with the red dot of a rifle laser sight on his forehead, raises his hand from inside a boat at the time of his capture by law enforcement authorities in Watertown, Mass., on April 19, 2013. (AP Photo/Massachusetts State Police, Sean Murphy, File)

When accused Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev is brought to trial later this year or early next, the life of the 20-year-old naturalized citizen won’t be the only thing at stake. In a very real way, the future of the death penalty — a barbaric relic of a bygone era abolished by more than two-thirds of the world’s nations — will also be on trial.

Legally, the decision to pursue execution was made by Attorney General Eric Holder. At Holder’s instruction, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Massachusetts filed a detailed eight-page Notice of Intent to Seek the Death Penalty on Jan. 30.

In the broadest sense, there are at least two reasons for Holder’s decision: First, the political backdrop of the continuing war on terror makes it imperative that the Obama administration appear strong in the face of danger.

Of course, there’s no explicit reference either to the president or the “war on terror” in the Notice of Intent. But the word “terrorism” appears in the document six times. The Notice recounts that Tsarnaev (who was born in Kyrgyzstan and whose family hails from Chechnya) “received asylum from the United States; obtained citizenship and enjoyed the freedoms of a United States citizen; and then betrayed his allegiance to the United States by killing and maiming people in the United States,” crimes the document characterizes as acts of “terrorism” rather than simply acts of murder, mayhem or aggravated assault. We are urged not only to condemn Tsarnaev but also to fear him.

There is nothing particularly unusual about the politics of fear being invoked in debates about the death penalty or street crime, generally. The politics of fear have driven our per capita incarceration rates to the highest in the world and left the United States as one of the leaders in the number of annual executions, trailing in recent years only such stalwarts of freedom and democracy as China, Iran, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, according to Amnesty International.

The politics of fear have also made and broken political careers in this country, consigning 1988 Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis to a humiliating defeat to George H.W. Bush after a Republican PAC ran a television attack ad about a weekend prison furlough Dukakis supposedly approved as governor of Massachusetts for convicted murderer Willie Horton. By contrast, the execution statistics racked up by George W. Bush while governor of Texas bolstered his tough-on-crime image and helped pave his way to the White House.

The capital case against Tsarnaev offers more of the same politics, except with foreign or foreign-born terrorists replacing marauding racial minorities like Horton, an African-American, as the fearsome malefactors. As a matter of constitutional principle, no one interested in due process should be swayed by fear. Standing alone, fear of the accused doesn’t justify another killing, even if ordered by a court and jury, especially when sentencing the accused to life in prison without the possibility of parole is a viable option.

The second reason behind Holder’s decision to seek the death penalty, however, is less easily countered: that the 30 federal offenses alleged against Tsarnaev are so severe that capital punishment is the only morally appropriate response. Among other crimes, Tsarnaev is alleged to have intentionally used a weapon of mass destruction near the finish line of the marathon, killing three people, the youngest an 8-year-old boy. At least 260 others were injured, including 16 who required amputations. The carnage, massive in scale, was inflicted on a crowd of innocents.

The Notice of Intent lays out the case for execution point by excruciating point. The names of the homicide victims — Krystle Campbell, Lingzi Lu and Martin Richard — are repeated in mantra fashion over and over, coupled with the name of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology campus police officer, Sean Collier, whom Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and his older brother Tamerlin allegedly shot as they made their getaway from the bombing site. The younger Tsarnaev also faces non-capital murder charges in Collier’s killing in state court in Massachusetts, which no longer has a death penalty.Even the staunchest abolitionist, after reading the Notice of Intent, will have to wonder if the death penalty is ever warranted, then surely it must be in a case like this. And if, as expected, Tsarnaev is found guilty, that is precisely the question his jury will have to answer.

Under the rules of “guided discretion” — the name given to the version of capital punishment that the Supreme Court’s 1976 decision in Gregg v. Georgia ruled constitutional — juries in capital cases are given the task of balancing and weighing aggravating and mitigating factors relating to the charged offense, as well as the defendant’s background and character, to determine who among those defendants convicted of murder should be sent to prison and who should be condemned to die. The system is designed to be rational and fair and to minimize the impact of emotion and bias in sentencing.

But despite all the subsequent efforts made by state legislatures across the country, as well as by Congress when it reinstated the federal death penalty in 1988, and by later court decisions aimed at achieving further refinements, the system has failed. The death penalty remains, essentially, what it has always been — an arbitrary, primitive state-sanctioned practice marred by racial and class disparities, fueled by rage and grief rather than reason, stoked by political animus, and without any more deterrent effect than long-term imprisonment.

In this respect, the Tsarnaev case is no different. Killing him won’t bring back the dead; it won’t heal the wounded. Nor will it end the war on terror. In fact, it may only prolong it.

What makes Tsarnaev’s case different from other death penalty ones is that its outcome will resonate far beyond the confines of a single prosecution, either prolonging the dark regime of capital punishment or signaling its ultimate and long overdue demise.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.