‘Díselo Ahora’: Why a Sentence Spoken in Spanish Matters

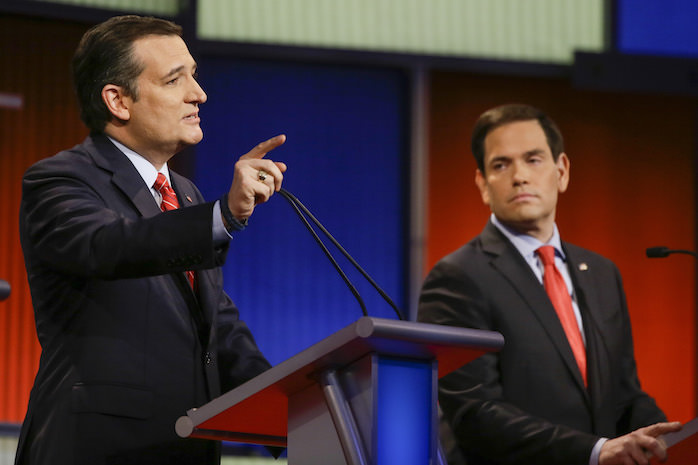

The recent sparring in Spanish between GOP presidential rivals Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz offers a glimpse into Americans’ shifting and sometimes conflicted views on heritage and language use in the U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz answers a question as Sen. Marco Rubio looks on during a Republican presidential campaign debate in Des Moines, Iowa, on Jan. 28. (Charlie Neibergall / AP)

Sen. Ted Cruz answers a question as Sen. Marco Rubio looks on during a Republican presidential campaign debate in Des Moines, Iowa, on Jan. 28. (Charlie Neibergall / AP)

Last year, The Economist reported that a bilingual Arizona reporter faced a backlash, with viewers complaining that her pronunciation of Spanish names was “overly Spanish.”

The pressure to suppress fluency in a second language has been great in the modern United States, particularly among conservatives in the political sphere. John McWhorter, a Columbia University professor, has pointed out that in early U.S. history, presidents were expected to have mastered French, but more recently bilingualism has been seen as a liability in U.S. politics. McWhorter says the reasons for this disdain have varied depending on which language is in question. He notes, for example, that Jon Huntsman, a 2012 Republican presidential candidate, was attacked for his knowledge of Mandarin Chinese because it seemed “ostentatious,” whereas rival Mitt Romney’s knowledge of French made him seem, to some, too tied to Europe. Secretary of State John Kerry’s fluency in French worked against him as a Democratic presidential candidate in 2004; he was attacked as an un-American snob overly sympathetic to French values at a time when many Americans were so anti-France that they referred to french fries as “freedom fries.”

The ability to speak Spanish carries another set of cultural implications, and politicians have spun their relationship to the language according to their audience.

In a 2007 speech, Newt Gingrich called English “the language of prosperity” and seemed to refer to Spanish as “the language of living in a ghetto,” a comment for which he was criticized and which he later tried to temper. Yet in a 2012 interview with Univisión’s Jorge Ramos, Gingrich greeted a group of students with a warm “Bienvenidos.”

Like Gingrich, Ted Cruz has used the word “ghetto” in connection with Spanish, contending that immigrants who do not learn English will be trapped in a “language ghetto.” But he also took out a campaign ad in Spanish that began “La historia de Ted Cruz es como la historia de muchas familias estadounidenses” (“The story of Ted Cruz is like the story of many American families”). The ad, which goes on to emphasize his Cuban heritage, implies that other immigrant families should identify with Cruz. For the most part, however, he has downplayed any connection to Latin America. He has chosen to call himself Ted rather than use his given name, Rafael Edward Cruz, and has refused to give interviews in Spanish, noting that his Spanish is lousy.

Unlike Cruz, Marco Rubio has highlighted his Cuban roots. During Wednesday’s GOP town hall in South Carolina, Rubio related personal stories about being the target of racism as a child and said he is making the Republican Party more diverse: “I got the endorsement of a governor of Indian descent [Nikki Haley], who endorsed a presidential candidate of Cuban descent, who tomorrow will be campaigning alongside an African-American Republican senator.” [Both of Haley’s parents came from India’s Punjab region.] Rubio has given interviews in both Spanish and English.

Jeb Bush, too, has touted his ability to speak Spanish, and pundits thought it would win him votes in the Latino community. The risks of emphasizing those connections and Spanish fluency, however, may be lower for Bush, a non-Latino candidate from an established political family, than they are for Cruz or Rubio. That did not stop Donald Trump from arguing, after hearing Bush speak Spanish, that candidates should set an example by speaking only English in the United States.

Given that Cruz has largely de-emphasized his Cuban roots, the most recent Republican debate included a surprising moment. It began when Cruz attacked Rubio’s immigration policies, citing an interview the Florida senator gave on Univisión. Rubio defended himself and jabbed at Cruz by pointing out that his opponent could not speak Spanish, presenting monolingualism as a deficiency. Rather than arguing, as Trump did, that candidates should speak only in English, Cruz responded in halting (but correct) Spanish, “Marco, si quieres, díselo ahora, ahora mismo díselo, en español, si quieres” (“Marco, if you want, tell them now, tell them now, in Spanish, if you want”). It may seem astonishing that Cruz, in the deeply red state of South Carolina, felt the need to defend himself against the charge that he could not understand Spanish. The moment was brief, and Rubio did not respond in Spanish, resorting instead to name-calling in English, saying Cruz was “a liar.”

Cruz’s response in Spanish may have been strategic. While speaking another language may not resonate widely among conservatives, it may bolster a candidate’s support among certain groups, even within the Republican Party. Paul Apostolidis, a political theorist and Whitman College professor, said of Cruz’s use of Spanish: “By staging a performance of Latino authenticity, Cruz was trying to energize and draw into his camp the small but significant constituency of Latino voters. In addition, Cruz’s core base of evangelicals likely would not be alienated—and may even have been favorably impressed—by Cruz’s use of Spanish, because conservative evangelicals recently have tried to maintain or present at least the appearance of multicultural diversity, while also being interested in outreach to continually growing Pentecostal and other evangelical populations in Latin America.”

Cruz’s reaction in Spanish has generally received little media attention. It is worth noting that his response has been transcribed and sometimes translated incorrectly in most of the English-language publications I’ve seen, including a confusing article in The Washington Post, as well as pieces in The Huffington Post, Boston.com and Yahoo! Politics. Most quoted Cruz as saying “dicelo,” a construction that does not make sense in Spanish. The error in the transcriptions may be in part because Cruz’s Spanish is not entirely fluent. He paused in a strange place, breaking up the “díselo,” which should be a fluid command. The Washington Post, the only publication that has attempted to analyze the exchange between Rubio and Cruz in any depth, corrected the error after readers complained in comments but left two other mistakes, including “ahora el mismo,” which also makes no sense in Spanish in that context. The journalist also only translated the sentence “roughly,” as if an accurate translation were not possible. This may seem nitpicky, but these errors raise questions about the place of Spanish in the mainstream media. Considering the number of people in the U.S. who speak Spanish either natively or as a strong second language, it is surprising that more editors did not catch these mistakes.

Despite the lack of careful attention given to the exchange between Rubio and Cruz, it was a significant moment that deserves analysis. Bilingualism and Latino identity were portrayed in front of an English-speaking, conservative audience as assets rather than liabilities. Fluency in Spanish, however, is not likely to win votes for any of these candidates. An MSNBC/Telemundo/Marist poll in December found that Democrat Hillary Clinton’s lead over all Republican candidates had widened significantly within the Latino population, suggesting that Latino voters are swayed more by ideology than by cultural identity.

Victoria Livingstone is a visiting assistant professor of Spanish at Whitman College in Washington state. She holds a Ph.D. from Boston University and has published translations, book reviews and articles on topics ranging from crowd-sourced translation to social inequality in Brazil.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.