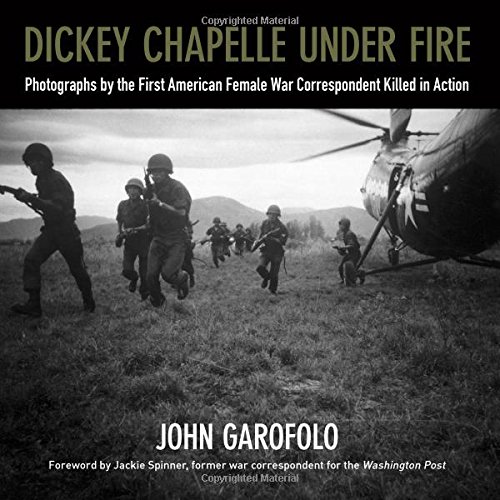

Dickey Chapelle Under Fire

Dickey Chapelle, the first female American war correspondent to be killed in action, is featured in a new pictorial memoir that collects her photos and notebooks from World War II to Vietnam.

“Dickey Chapelle Under Fire: Photographs by the First American Female War Correspondent Killed in Action” A book by John Garofolo To see long excerpts from “Dickey Chapelle Under Fire” at Google Books, click here.

Fifty years ago, 47-year-old photojournalist Dickey Chapelle earned the unfortunate distinction of being the first female U.S. war correspondent killed in action. While on patrol in South Vietnam, she was fatally struck in the neck by shrapnel from a tripped explosive. She had often said, foreshadowing her demise, “When I die I want it to be on patrol with the United States Marines.”

A Marine honor guard escorted her body home to Milwaukee where she was buried with full military honors, a rarity for a civilian. Dickey Chapelle was no ordinary gal.

Although her death was national news in 1965, her story is not well known despite the fact that Chapelle is part of an elite group of female war correspondents including Margaret Bourke-White, Martha Gellhorn and Marguerite Higgins.

The author of a new pictorial memoir, “Dickey Chapelle Under Fire: Photographs by the First American Female War Correspondent Killed in Action,” John Garofolo, who is also an Iraq War veteran, hopes the book will bring Chapelle’s remarkable story well-earned recognition. A collaboration with the Wisconsin Historical Society, Garofolo drew from its extensive collection of Chapelle’s photos and notebooks spanning World War II to Vietnam. The result of his 24-year odyssey, which began with a screenplay, is a well-crafted, captivating photo essay of the conflicts of the 20th century as told through the lens of a correspondent who unabashedly risked her life to get the story.

At just 5 feet tall, Chapelle’s petite frame was packed with guts and ambition. Early on she was willing to break the rules to get “as far forward to the action as they would let me.” Her fearless tenacity often came with severe repercussions.

Chapelle came along in a time when women were not welcome on the battlefield. They had to fight, lie and finagle their way to the front lines. The lack of latrines and separate living quarters were the standard excuse from the brass.

Chapelle’s answer: “Well sir, I’m sure the Army has solved more difficult problems than that.” In 1962 she wasn’t as diplomatic when an officer denied her access to a field operation, arguing there were no toilets for women in the jungle.

“Listen soldier,” she replied, “don’t worry about me, and when I have to, I can piss standing up straight just like you do!”

These quirky anecdotes, culled from her archives, add character to an already fascinating persona.

Chapelle abhorred the censorship of photos showing the hell of war, censorship that favored morale-boosting propaganda pictures for the folks back home. On several occasions her work was deemed “too dirty” for publication, including many of her images from Iwo Jima and Okinawa, two of the bloodiest campaigns of the Pacific theater.

When Chapelle started out in February 1945, she was assigned to photograph the wounded on board the hospital ship USS Samaritan. She got her first taste of action when granted permission to visit the front lines of Iwo Jima. She was hooked.

A few months later, during the invasion of Okinawa, Chapelle was covering blood donations aboard another hospital ship. Defying direct orders not to go ashore, the feisty 24-year-old talked her way onto the island, and embedded with a field medical unit of the Sixth Marine Division for 10 days before being discovered. She was placed under arrest and stripped of her press credentials.

Surprisingly, photography was not Chapelle’s first choice. She was born Georgette Louise Meyer on March 14, 1919, in Milwaukee, to a long line of German pacifists. After watching a documentary on explorer Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr., she adopted his nickname “Dickey,” and was determined to become, like her hero, a pilot. Her nearsightedness quashed that dream but not her enthusiasm for adventure.

Hints of her untamable spirit are visible in childhood photos, where she appears defiant and uncomfortable when posing in dresses. She exudes genuine excitement, however, standing next to a plane.

At just 16, Chapelle earned a scholarship to study aeronautical design at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Preferring to hang around the Boston Navy Ship Yard learning how to set turbine blades, she flunked out after two years.

While visiting Havana with her grandparents, 20-year-old Chapelle witnessed a fatal plane crash during an air show. She ran to a pay phone and called the story in to The New York Times. An editor at Trans World Airlines was impressed when he learned how the Times had gotten the story, and Chapelle was offered a job in the publicity department of Trans World Airlines. She soon moved to New York City where she met her husband and photography instructor Tony Chapelle.After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Look magazine sent Chapelle to Panama to cover Army Bushmasters training. She eventually made her way to the South Pacific where she became the first female photographer to cover the war with Japan.

Stepson Rob Chapelle acknowledges that although Chapelle’s technique may have been lacking — wasting time with a light meter, for example — it didn’t diminish the candid nature and authenticity of her work. More than 150 engrossing black and white photographs in Garofolo’s book display Chapelle’s talent across a wide spectrum of war, its mechanisms, casualties, revelry and humanity. She would capture, with equal aplomb, both the execution of an enemy combatant by an Algerian firing squad and then a U.S. paratrooper cheerfully dancing with fourth-graders after their teachers fled from violence in Santo Domingo. Her most reproduced photo, “The Dying Marine,” shows an agonized corporal on a gurney, his gut oozing blood through his uniform, while “The Laughing Marine” shows a young man expressing the joy of a letter from home.

A wide-angle photo of a bombed out landscape in Iwo Jima shows a Marine resting atop the remains of a bunker. If you look a little closer, several helmeted faces can be seen popping up like gophers from their foxholes, one smiling directly at the camera.

Returning home without any credentials at the end of World War II, Chapelle and her husband embarked on a six-year journey across postwar Europe, providing relief work in a truck that served as their office and living quarters. During this time they also worked in the Middle East, Iraq, Asia and India, capturing unexpected photos of a young King Hussein of Jordan and Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

Soon after returning to New York in 1952, Chapelle divorced Tony after learning of his infidelity. Asked then if a woman can be a foreign correspondent and a wife, she answered, “Never at the same time.” It’s telling that no one wondered whether a man can be a foreign correspondent and a husband. The answer would have been the same.

For the next 10 years, Chapelle would cover conflicts in Korea, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Lebanon, Kashmir and Hungary.

While transporting medicine to Hungarian refugees during the 1956 uprising, Chapelle was captured by the Russians and held in a Budapest prison for two months, tortured and threatened with execution as a spy. I would have liked to see more details on her experience in captivity, to add dimension and vulnerability to her seemingly indestructible facade. It would also have addressed the life-threatening hazards of her occupation that continue to this day.

After her ordeal, she gained a reputation with rebel leaders around the world. Algerian rebels smuggled her into their country to help tell their side of the story. In 1958 she accompanied Fidel and Raúl Castro into the jungles of Cuba during the revolution.

Assisting in the making of bombs and jumping out of airplanes with the 101st Airborne earned her respect, paving the way for female correspondents such as Christiane Amanpour, Lynsey Addario and the late Marie Colvin.

Chapelle accompanied every branch of the military during her career, but the Marines remained her favorite. “They taught me bone-deep the difference between a war correspondent and a girl reporter,” she wrote.

Her work has graced the pages of National Geographic, Life magazine, Reader’s Digest, Cosmopolitan and The National Observer. She penned eight books, including her 1961 memoir, “What’s a Woman Doing Here?” In 1962 she received a George Polk Award for her coverage of the fighting in Vietnam, during which she made several parachute jumps into enemy territory. Despite all the accolades (which included a song, “Pearl’s Eye View (The Life of Dickey Chapelle),” recognition of her work was elusive.

Chapelle was clearly happiest in the field, a delight that shines through in several photos. Most telling is the snapshot of her trudging through a muddy stream with South Vietnamese soldiers in 1961. Wearing her signature Harlequin glasses, fatigues, Australian bush hat and pearl earrings, the exuberant smile on her face leaves no doubt she was elated to be there.

One of the last images in “Dickey Chapelle Under Fire” is Associated Press photographer Henri Huet’s indelible photo of Chapelle’s lifeless body, face down in the dirt, receiving last rites from a Navy chaplain. Chapelle’s face is turned toward the camera, partly covered by her curled hand. Her Australian bush hat lies on the ground next to her where it fell. Just moments before her death, she reportedly whispered, “I knew this was bound to happen.”

Huet would later perish with three other photojournalists in a helicopter crash in Laos in 1971.

In the end, Dickey Chapelle had earned the respect not just of her fellow correspondents but also of her beloved Marines. After her death, they dedicated a field hospital in her memory; created the Dickey Chapelle Award, which honors a woman who has, in the words of the Marine Corps League, “contributed substantially to the morale, welfare and well-being of the officers and men and women of the United States Marine Corps”; and erected a monument near the spot she was killed. The inscription reads, “She was one of us and we will miss her.”

View Dickey Chapelle’s photos at the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.