Despite Chernobyl, Belarus Goes Nuclear

Thirty years after the Chernobyl accident in Ukraine, one of its neighbors is close to completing its own nuclear power station.

By Kieran Cooke / Climate News Network

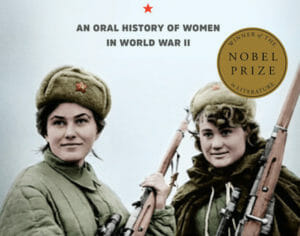

Ostrovets takes shape: The nuclear power plant is to be commissioned in 2018. (Paul Osipoff © 2016)

This piece first appeared at Climate News Network.

MINSK — Nuclear fall-out, like carbon dioxide and other climate-changing greenhouse gases, does not respect national borders.

On 26 April 1986 an explosion at the Chernobyl power plant, in Ukraine but only a few kilometres from the southern border of Belarus, sent clouds of radioactive dust into the atmosphere.

It’s estimated that up to 70% of the fall-out from what rates as the world’s worst nuclear accident fell on Belarus, affecting hundreds of thousands of people.

Now, 30 years later, Belarus itself is going nuclear — building its own 2,400 MW nuclear power plant at Ostrovets in the north-west of the country, close to the border with Lithuania.

Nina Rybik was born in the southern Belarus village of Ulusy, a few kms away from the Chernobyl plant.

“My children and I had already moved away from the area, but my parents had to leave soon after the explosion, and could not go back there to live”, says Nina.

“Now we are allowed to go there only once a year, to visit our ancestors’ graves. Our old house is falling down, our lands are useless now. It is all so sad.”

Through a strange twist of fate, Nina now finds herself working only a few kilometres from the new plant at Ostrovets. Her mother died a few years ago: her father lives with her.

“Our design and construction methods

are among the safest in the world.

We are proud to have such a plant in Belarus.”

“At first we felt strange, living once again so close to a nuclear site. But then I think that accidents can’t happen twice. I’m confident that the new plant will be safe — Belarus needs energy, and nuclear power is the only way to guarantee that.”

Nuclear power enthusiasts say building plants like Ostrovets is a key way of securing energy supplies without causing a further build-up of greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere.

Opponents though say no matter how strict the safety regulations, catastrophic accidents like Chernobyl are always possible. They also say the whole issue of storing nuclear waste — radioactive for generations — has still not been tackled, and that the costs of nuclear power are spiralling out of control.

The first power unit at Ostrovets is due to start operations in late 2018. More than 6,000 people are working at the kilometre-square site, building cooling towers and giant containment vessels which will enclose the nuclear reactor at the heart of the plant.

Vladimir Gorin, deputy chief engineer at the plant, told one of the first media groups to visit that, while the reactor at Chernobyl had no outer containment shell, Ostrovets will have a double wall made of thick steel and concrete. Officials say the whole containment structure will be further secured by large quantities of iron bands.

“Our design and construction methods are among the safest in the world”, said Gorin.

“We follow all international standards and checks at every stage of building. We are proud to have such a plant in Belarus.”

It is unclear how the nine million population of Belarus — some of whom are still suffering health problems caused by the Chernobyl explosion — feel about Ostrovets.

Close to Vilnius

Belarus is tightly controlled by the regime of Alexander Lukashenko, in power for the last 21 years. Officials at Ostrovets say a poll carried out by a government-run institute found that more than 60% were in favour of the plant.

Irina Sukhy of the Green Network, a Belarus environment non-governmental organisation, says no proper public hearings have been held on Ostrovets, and those who raised questions about the plant have been harassed and arrested.

At present Belarus imports more than 80% of its primary energy, mostly from Russia. One of the main reasons cited by Minsk for the construction of Ostrovets is to lessen its dependence on Moscow for energy supplies.

Government critics point out that Ostrovets has been designed and built and will be operated mainly by Rosatom, the Russian state nuclear company. The Russians will also be responsible for disposing of the nuclear waste produced at the plant.

Neighbouring Lithuania — a member of the European Union (EU) — has raised strong objections to the plant. Ostrovets is less than 50 kilometres from Vilnius, Lithuania’s capital.

Vitalijus Auglys, an official at Lithuania’s Ministry of Environment, says Belarus has not fully answered questions about the safety of the Ostrovets plant and is in contravention of international conventions on building nuclear facilities — accusations the government in Minsk denies.

Lithuania, as part of its 2004 accession agreement with the EU, agreed to close its own Ignalina nuclear facility, a plant similar in design to Chernobyl.

Officials at Ignalina say decommissioning at the plant will take till 2037 to complete and will cost about €3 billion. The Lithuanian government has not fully ruled out constructing another, more modern, nuclear facility on the same site.

Kieran Cooke, a founding editor of Climate News Network, is a former foreign correspondent for the BBC and Financial Times. He now focuses on environmental issues.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.