Death for the Disabled: Should We Kill Freddie Lee Hall?

The U.S. Supreme Court now faces what may be the most important legal challenge to the death penalty in years.

Like many death row inmates across the country, Florida’s 68-year-old Freddie Lee Hall is mentally disabled. The question is whether he is too disabled to be executed — an issue that now will be decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in what many observers believe is the most important legal challenge to the death penalty in years.

In 1978, Hall was convicted of murdering a pregnant housewife and a deputy sheriff, both gruesome and heartless acts. But in 1992, at one of Hall’s many post-conviction resentencing hearings, a Florida judge found that Hall had been “mentally retarded all his life.”

In a later proceeding (Hall v. State), two state court appellate judges wrote that Hall had an IQ of 60, suffered from organic brain damage, had the short-term memory of a first-grader and was raised under the most “horrific family circumstances imaginable.” Among other forms of abuse and torture suffered at the hands of his mother, relatives and neighbors, Hall was tied up in a burlap sack as a youngster and swung over an open fire, suspended by his hands from a ceiling beam, beaten while naked, made to lie still for hours underneath a bed and repeatedly deprived of food.

Last year, after Hall had exhausted his state-court appeals, the Florida Supreme Court deemed him mentally fit for lethal injection, as during the course of his long incarceration he had registered scores of 80, 73 and 71 on Wechsler WAIS III IQ tests administered at the direction of prison authorities. Under Florida law, any death row inmate scoring above 70 cannot be considered disabled.

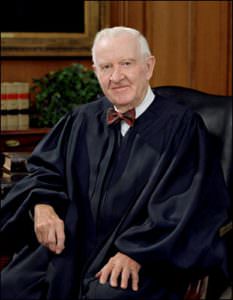

In agreeing to review Hall’s case, the U.S. Supreme Court will decide whether Florida’s bright-line IQ cutoff for defining mental disability runs afoul of the high court’s 2002 holding in Atkins v. Virginia. In Atkins, a bitterly contested 6-3 opinion written by since-retired Justice John Paul Stevens, the court held that evolving standards of decency and an emerging national consensus indeed precluded the execution of inmates deemed “mentally retarded,” the term then widely used before it was cleaned up, sanitized and replaced with the label “disabled” by mental health organizations.

Justice Stevens also reasoned that executing the mentally disabled would do little to advance two of the primary justifications of capital punishment — retribution for and deterrence of capital crimes — as severe mental deficits operated to diminish a defendant’s culpability and made it less likely that disabled defendants would understand and appreciate the possibility of execution as a penalty and, as a result, control their conduct based upon that understanding.

On a practical level, the court in Atkins elaborated that a finding of mental retardation required proof of three conditions: (1) sub-average intelligence, most commonly measured by IQ tests, (2) lack of fundamental adaptive social and practical life skills, and (3) the onset of such deficiencies before the age of 18. But, as in so many other areas of recent Supreme Court jurisprudence in which the court has endorsed a new era of federalism, the opinion left it up to the states to devise their own definitions of mental disability.

Florida is one of 10 states (the others are Arkansas, Delaware, Idaho, Kentucky, Maryland, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and Washington) that use IQ scores of 70 as a bright line for establishing disability. The remaining states that authorize capital punishment generally align with the approach of the American Psychiatric Association, which instructs that disability should be assessed not only with a range of standardized tests that take into consideration what testers call standard errors of measurement to account for the imprecision of test results, but with clinical evaluations of everyday tasks such as language ability, social judgment and personal care.

Although the high court’s review of Hall’s death sentence will technically be limited to his mental condition, the case will once again highlight the shameful nature of Florida’s criminal justice system, which gained international attention and opprobrium with the exoneration of George Zimmerman under the state’s “stand your ground” law in the slaying of Trayvon Martin.

When it comes to capital punishment, Florida is among the nation’s most draconian venues. In addition to having the country’s second largest death row population after California, the Sunshine State permits juries to return death verdicts on simple majority votes. Every other death penalty jurisdiction except Alabama (which requires a supermajority jury vote of 10-2) mandates jury unanimity.

On a more fundamental level, the Supreme Court’s review of Hall’s sentence will highlight the irrationality, arbitrariness and cruelty of the death penalty in general. According to Amnesty International, more than two-thirds of the world’s nations have abolished the death penalty in law or practice. Sadly, the U.S. is not among them.

To be sure, Freddie Lee Hall’s case will not put an end to capital punishment in the U.S. No sitting member of the current court under the leadership of Chief Justice John Roberts has ever expressed the view that the death penalty in all instances is unconstitutional, as the late great Justices William Brennan and Thurgood Marshall time and again argued. Still, there is reason to hope for a small victory in Hall’s case, and that by agreeing to review Florida’s death penalty scheme, the court will at least narrow the scope of the ultimate punishment. These days, narrow victories may be the best we can get.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.