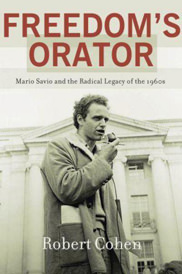

David Kipen on ‘Freedom’s Orator’

Robert Cohen succeeds in drawing Mario Savio back into the historical spotlight, though his biography of the 1960s student firebrand is stingy with details.Robert Cohen draws Mario Savio back into the historical spotlight, but his biography of the 1960s student firebrand is short on details.

If Columbia students were marching on Albany this year and a biography of Mark Rudd had just come out, you could bet the book wouldn’t go unreviewed in the so-called national media. Berkeley has erupted again, and a fascinating biography of Mario Savio — a figure far more influential than Rudd, and not just because he helped lead a sit-in at Berkeley four years before the Columbia protests — has just come out. But its author, Robert Cohen, would have to stage a sit-in at 42nd Street and 8th Avenue for much of anybody to notice. Could it be that, for all the supposed decentralization of media in the age of Twitter, what’s left of the commentariat is more Manhattanized than ever?

That would be a shame, because “Freedom’s Orator: Mario Savio and the Radical Legacy of the 1960s” rescues from creeping amnesia a student firebrand perhaps second only to Tom Hayden in his rhetorical gifts. What Hayden did in his epochal Port Huron Statement over a stretch of weeks — give eloquent voice to a generation — Savio did from the top of a squad car on no sleep. “Freedom’s Orator” succeeds in taking us back to a time when Berkeley students would actually fight not just to speak freely on campus, but also to “emphasize intensive study of the classics in intimate seminars.” The more things change, apparently, the more they get completely different.

Mario Savio grew up Sicilian in Queens, an altar boy and a physics prodigy. He had a paralyzing stammer, which Cohen persuasively argues made his later leadership in the Free Speech Movement not so much ironic as deeply personal. Savio loved free speech as maybe only someone denied it since childhood could. It wasn’t till his fairly banal high-school valedictorian address that he discovered public speaking didn’t compound his disability, but actually seemed to cure it.

For most of his life, Savio had a horror of private, individual speaking. Fired with the idealism of his work in Mississippi during the Freedom Summer of 1964, he resisted the cult of personality with which journalists kept trying to saddle him. In the unpublished memoir Cohen tantalizingly quotes from, Savio consistently deflects credit toward his comrades for the movement’s success in overturning UC Berkeley’s limits on free speech, and away from himself.

Freedom’s Orator: Mario Savio and the Radical Legacy of the 1960s

By Robert Cohen

Oxford University Press, 544 pages

In that sense, alas, Savio got the biographer he deserved. About Savio’s private life, Cohen is discreet to the point of incuriosity. The only major exception to this reticence comes when Cohen turns up evidence of Savio’s childhood molestation by a relative. Otherwise, the author checks in on Savio’s personal doings only intermittently, and even then with all the depth and perspicacity of a class notes entry by a none-too-close friend: Savio “had recently become engaged to Suzanne Goldberg,” we learn in passing, and 13 pages later that his family “now included Suzanne and their son Stefan.”

On the one hand, an aversion to prurience is a desirable quality in a book about and for serious people, which “Freedom’s Orator” most definitely is. Yet if the personal is political — as so many of Savio’s co-generationists legitimately argued — then who we are remains relevant to what we say, and think, and try to do. Whom we marry, or don’t, and the children we bear, or don’t, bear in turn on the ideas we espouse, and hope to embody. Mario Savio had a mental breakdown later in life and was institutionalized, only to re-emerge as a loving though flawed husband, father, teacher and activist. That’s a whale of a story, but, despite all Cohen’s research, we glimpse it only at infrequent intervals, as if on visiting days.

Amid exhaustive accountings of arcane schisms and doctrinal splits, Cohen can be stingy with some details. We do discover, fascinatingly, that a viewing of “Becket” — the 1964 movie from Jean Anouilh’s play, starring Peter O’Toole as Henry II and Richard Burton as the troublesome priest pricked by conscience — probably had an important influence on Savio’s words and ideas atop a police car a couple of nights later. But other, fetishistic if forgivable, questions nag. Who christened the Free Speech Movement, anyway? And you don’t have to be a quondam museum curator to wonder: Rusting on what municipal surplus lot might that fateful police cruiser be found today?

Prophetically, Savio’s last campus crusade for justice had less to do with free speech than with student fees. This year, 36 years after Savio thrillingly — and effectively — exhorted his peers to “put your bodies upon the gears and … make it stop,” UC students have been demonstrating mostly for the right not to see a good education priced beyond their reach. Also this year, as in 1964, the kids won. They dodged a bullet last month in California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s proposed budget, which balances precariously and fleetingly on the backs of the poor, the sick and the elderly instead of their own. In state government, as in the office of any decent book review section, it’s triage every day.

In one sense at least, Schwarzenegger’s decision was exactly the right one. It’s a bet on the future of California. If he had crucified University of California students to spare the needy, instead of the other way around, the needy would have had no opportunity to pay the students back. In the years ahead, however, with libraries, community health centers and other public institutions slashed to the marrow, these students will have more than enough opportunities to service their debt of gratitude. Like Savio in Cohen’s imperfect but useful book — the altar boy who lost God but found a different calling — they should remember the story of the thief who was spared. Others will die for the UC class of 2014, just as Jesus died in place of Barabbas. This is a crime, but it will be a tragedy only if the victorious students forget how much more they owe, now, than just student loans.

Thanks to the pitiless Darwinism of YouTube, Savio’s legacy primarily rests on his brief, astonishingly extemporaneous “bodies upon the gears” speech, delivered right before the Free Speech Movement’s climactic sit-in on Dec. 2, 1964, and included here in a 75-page appendix of Savio’s speeches and writings. In a way, it’s a speech made for YouTube, since it starts out with Savio’s fairly extraneous trash-talking at the expense of the student body weenie up before him, and winds up with a movie announcement plus his short, almost Ed Sullivan-style “take it away” intro of Joan Baez. In between, the nut of his soliloquy is all but made for YouTube’s pruning.

Savio gives ragged but eloquent voice to the rage and especially the pain of a cohort that, in the words of a John Updike poem, did not yet know it was a generation. “There’s a time,” he says, unmistakably wincing, “when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part. …” Refusing to get sidetracked by the inadvertent rhyme, he drives on: “… you can’t even passively take part. And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop.”

So long as we’re discussing Berkeley, one of the last campuses that still offers a degree in rhetoric, it may be worth uncoiling a last strand or two of Savio’s powerhouse speech. The “bodies upon the gears” imagery is straight out of Chaplin’s “Modern Times,” of course. And “make it stop” becomes the perfect phrase, half rallying cry and half tantrum, to bring this youthful incantatory litany to a halt. With it, Mario Savio — who grew up considering the priesthood and wound up a plaster saint to Cohen, but an enduringly human inspiration to generations beyond just his own — Savio found the congregation he was born for.

|

David Kipen is the author of “The Schreiber Theory: A Radical Rewrite of American Film History.” Until January 2010, he was the literature director of the National Endowment for the Arts. He served from 1998 to 2005 as book critic, and before that book editor, for the San Francisco Chronicle. He lives in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles and can be reached at [email protected]. |

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.