David Foster Wallace: A Life

A new biography, "Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story," has collected fascinating details of David Foster Wallace's life, but fails to examine his development as a writer.

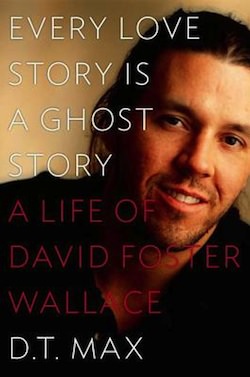

“Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story: A Life of David Foster Wallace” A book by D.T. Max

“How,” writes D.T. Max in his biography of David Foster Wallace, “Every Love Story Is A Ghost Story,” “do you write about dullness without being dull?”

Max is referring to a literary conundrum that Wallace faced late in his career, and though he doesn’t seem to realize it, he’s also referring to his own problem as a biographer. David Foster Wallace is the ultimate postmodernist neurotic spoiled literary brat. He wrote some dazzlingly brilliant short fiction, a handful of truly interesting essays, and there are sections of his gargantuan novels, the best known of which is “Infinite Jest” (referred to by a novelist friend of mine as “the infinite novel”), that match up with the best American writing over the last 30 or 40 years. Or would, that is, if future readers less taken with Wallace’s rock star persona care to go back and mine the nuggets.

Max has collected pages of fascinating details: an early memory of Wallace watching his parents holding hands in bed, reading “Ulysses” to each other (his father taught philosophy at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and his mother was a college English teacher); Wallace’s love of Scottish battle paintings (it would be nice to know if they were depictions of his namesake, William Wallace); and that he was a Reagan supporter for most of his life. Max has also given us some that are less fascinating, such as long lists of TV shows Wallace watched religiously and his favorite rock bands (real garbage like KISS, REO Speedwagon and Styx, though as he got older his taste got better with Bruce Springsteen and Neil Young).

Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story: A Life of David Foster Wallace

By D.T. Max

Viking Adult, 368 pages

The fact, though, is that aside from his writing, Wallace never really did anything very interesting. After high school his life pretty much descended into a dreary litany of depressions, anxiety attacks, affairs, alcohol, drugs and failed attempts at rehab, finally ending with his suicide in 2008 at the age of 46.

With no compelling narrative of Wallace’s life, Max needs some incisive and original critical analysis of the literary influences that shaped Wallace’s development as a writer. But I came away from “Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story” without the slightest idea of what Wallace read and what influenced him as a writer outside of interminable mentions of Thomas Pynchon. We’re told that Walker Percy gave him “the creeps” (why, exactly?). He read “The Armies of the Night” and compared its author, Norman Mailer, to Hitler. John Updike “didn’t do it for him: I don’t hear the click.”

What about the entire spectrum of American literature? Was William Faulkner’s subject matter too dated for him, F. Scott Fitzgerald too romantic, Willa Cather too earthy? We’re not told that he even read them. What of the other major figures of American or foreign literature since World War II? If he read Vladimir Nabokov it isn’t mentioned. What of the Latins — Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Mario Vargas Llosa? One would like to know Wallace’s reaction on reading James Joyce, but we’re not informed whether he did. We learn instead that a writer who was obsessed early on with the wordplay and mimicry of Pynchon later outgrew his influence.

“He reluctantly acknowledged,” writes Max, “that he might suffer from ‘a basically vapid urge to be avant-garde and post-structural and linguistically callisthenic — this is why I get very spiny when I think someone’s suggesting this may be my root motive and character; because I’m afraid it might be.’ ”

It’s a shame, really, that some of Wallace’s uncritical critics never suggested to him that he was right about himself and his work.

|

To see long excerpts from “Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story” at Google Books, click here. |

We don’t know what kind of writer Wallace would have morphed into if he had lived — a fascinating possibility is an American Dostoyevsky. Max tells us that Wallace had ” … over the years become deeply attracted to the Russian’s writing and life. The parallels between Dostoyevsky’s and his own certainly caught his eye, as they had at Grenada House [a detox clinic in Massachusetts]. Was his time there comparable to Dostoyevsky’s exile in Siberia … ?” The comparison of Grenada House to Siberia is rather silly. But Wallace’s love for Dostoyevsky is intriguing. Would it have pulled him more in the direction of what is often called moral fiction and away from the hip irony and sterile word games of so much of his early writing?

Even more interesting is Wallace’s attraction late in life to the work of Albert Camus. “He’s very clear as a thinker — and tough — completely intolerant of bullshit,” Wallace wrote to a friend. “It makes my soul feel clean to read him.” This comes on page 298 when Wallace doesn’t have much longer to live. It’s hard to read Wallace’s words and not wonder whether he had read Camus’ startlingly lucid tract, “The Myth of Sisyphus,” with its famous opening line that, in retrospect, seems chillingly prophetic: “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide.”

I think I would have read with relish the writer Wallace wanted to become. As it stands now, I wince when I read remarks like Rivka Galchen’s in The New York Times: “Wallace has given as much to literature as any contemporary American writer,” a judgment that insults every new book produced by Daniel Woodrell, Marilynne Robinson and, yes, Wallace’s good friend, the much maligned Jonathan Franzen.

Max has toiled valiantly in the service of his subject, but the book never really takes off. Even with Wallace’s enormous output, the promise so many saw in him was unfulfilled at the time of his death — and, despite the most impassioned efforts by his fans to see his work as something more, it always will be.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.