Danny Goldberg on the Digital Music Revolution

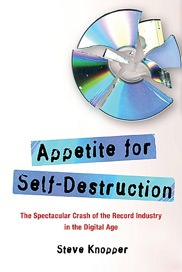

Is there a social consequence to the increasing numbers of consumers who expect to get information and entertainment for nothing? Can there be too much of a good thing? "Appetite for Self-Destruction: The Spectacular Crash of the Record Industry in the Digital Age” by Steve Knopper provides a useful autopsy.

book “Appetite for Self-Destruction: The Spectacular Crash of the Record Industry in the Digital Age” is an entertaining, well-written attempt to chronicle the economic decline of record companies, but his thesis echoes conventional wisdom that numerous tech-friendly journalists have expressed in recent years. It is heavy on schadenfreude and ridicule of record executives and light in grappling with the major questions raised by the digital world’s damage to the economic value of all intellectual property.

The damage to record companies coincided with a convergence of the interests of venture capitalists, avaricious Internet entrepreneurs and techie philosophers and fans, who combined to create a popular philosophy that brandished the phrase “information wants to be free” like a sword of futuristic wisdom. The Internet explosion made this argument irresistibly hip to many young opinion leaders, and the enormous profits of the Internet bubble gave political power to the companies that were benefiting.

In fact, the phrase “information wants to be free” was first used in the nuanced speech of Stewart Brand at the first “Hackers’ Conference,” in 1984, in which he said: “On the one hand, information wants to be expensive because it’s so valuable. The right information in the right place just changes your life. On the other hand, information wants to be free because the cost of getting it out is lower and lower all the time, so you have these two things fighting against each other.”

In the shrill euphoria of the next two decades, the word information came to include anything that could be digitized, and the concept that there were any moral grounds to balance the ease of distribution with the cost and difficulty of creation and marketing was drowned out. Brand’s thoughtful formulation was reduced to a five-word bromide that was deployed against record company executives and musicians who sought to protect the value of intellectual property. As a guide to social policy, “information wants to be free” was, in retrospect, the ’90s equivalent of the equally seductive and equally intellectually untenable slogan “Don’t trust anyone over 30” that had a brief vogue in the 1960s.

(Disclosure: I have made my living in the music business since the late 1960s, and I ran some divisions of major labels during the ’90s before any of the controversial fights or negotiations with Internet companies, in which I played no part. I currently manage musical artists, none of whom are currently signed to major labels, but it’s not impossible that some may be in the future. Knopper interviewed me for the book, and his brief references to me are friendly and the quotes he used accurate.)

The best part of “Appetite for Self-Destruction” is a detailed history of a series of unsuccessful and sometimes laughable efforts of record companies to deal with the tectonic shift brought on by home computers and the Internet. Knopper’s argument is that more intelligent, ethical, tech-savvy record company leaders would somehow have avoided the decline of the record business, hence the term “self-destruction.” However, he betrays a bias by throwing in sensational music business dramas irrelevant to his theme, such as pages devoted to real and alleged payola, and various forms of drug abuse and thuggery that cropped up in the business over the last few decades.

Early in “Appetite for Self-Destruction,” Knopper quotes former Warner Records and EMI CEO Joe Smith as observing, “This business ain’t full of Martin Luther Kings.” It says something about the emotional power of music that anyone would expect sainthood in its executives, but in the real world the absence of “Martin Luther Kings” is notable in virtually all businesses. Internet romanticists liked to ridicule the often implausible claims of record execs that they were looking out for the artists, since these were, at times, the same companies that had been successfully sued by artists for inaccurate accounting. However, the venture capitalists were not funding business plans to advance a utopian vision. The tech companies were every bit as self-interested and just as much driven by short-term profits as the most venal record company execs. At least the record companies sometimes paid artists something.

There is no denying that the major record companies made mistakes, which leaders of other media were able to learn from and avoid (although not with demonstrably better results). There is, however, no evidence that there was any strategy, regardless of who ran the record companies or what decisions they made, that could have stopped fans, especially young fans, from legally or illegally copying or downloading music instead of buying it.

The greatest hits of record company failings are chronicled by Knopper in a series of brief interstitial chapters the author calls “Big Music’s Big Mistakes.”

Knopper implies that if record companies had been nicer to their customers, if they were run by corporate saints, then things might have worked out differently. If only they hadn’t charged so much for CDs even after the per-unit manufacturing cost went down; if only they hadn’t abandoned the commercial single when it ceased to be sufficiently profitable; if only they hadn’t cooperated with Best Buy and Wal-Mart at the expense of indie stores; if only they hadn’t sued customers for illegal downloading, etc. etc. Referring to the fact that some of Sony/BMG’s ill-fated watermarked CDs damaged some computers, Knopper writes: “This lack of empathy reinforced Napster-era beliefs that the music industry was more interested in suing and punishing its customers than catering to them.” This litany of real and imagined insults to the consumer ignores the central reality of what caused the decline of record sales: the ability of fans to get albums free. The problem wasn’t the price. In the eyes of many consumers, it is simply impossible to compete with free. Many of the same people who won’t pay $15 for a CD will fork over $20 for a T-shirt or $30 to $200 per ticket for a concert by the same artist. This is not because the IQ or moral compass of concert promoters or merchandising companies is higher than that of record executives, but because it is infinitely more difficult to get into a concert without a ticket or to shoplift a T-shirt than it is to burn a copy of a CD. Security guys at arenas are not particularly empathetic to people who try to sneak in without paying, but that hasn’t hurt the concert business.

Missing from Knopper’s narrative is the story of the incredible wealth that was accrued by a few hundred computer and software entrepreneurs and executives who fueled and exploited the cynical notion that music “should be free,” that music was a “killer app” that drove traffic, computer sales, etc., at the expense of artists and the people who worked with and invested in them. The fact that many record company executives were inept at PR, wildly outspent in Washington and in some cases personally unappealing did not mean that the society’s swift capitulation to the devaluation of intellectual property was a good idea.

Knopper is a good writer with a keen sense of some of the comic hubris that record companies produced. He correctly identifies a number of Internet marketers at record companies who had to overcome roadblocks within their own companies in order to use the Internet as a positive promotional tool. They faced embattled salesmen and lawyers who were trying vainly to stop the deterioration of sales and CEOs who had to deal with pressures from their boards and Wall Street analysts. However, Knopper errs in conflating conscious promotional tactics with an “anything goes” mentality that many Internet companies adopted. There is no question that in certain situations, artists and record companies and other content owners can benefit by making some material available free in order to bond an artist with fans in the hope of selling to them in the future. But there is a huge difference between the Grateful Dead choosing to let their fans tape and disseminate their live shows and those same fans deciding they have the right to take any music they want regardless of whether the artists want them to or not.

Knopper makes much of the record companies’ seemingly pyrrhic victory in shutting down the original version of Napster through lawsuits. Various disgruntled former executives claim that if the companies had bought Napster instead, they could have communicated directly with their tens of millions of fans and somehow short-circuited the migration of those fans to other, more-elusive systems where they got free music illegally, almost always with impunity. But as long as the technology made free music possible, why would any fee system, whether subscription, discounted or artist-friendly, have made more of a dent than i-Tunes has?

There is no question that many aspects of the digital explosion have been good for music fans and musicians. Recording and video costs are a fraction of what they were in former times, and niche artists have the ability to identify and bond with fans in a way that was impossible in the pre-digital world. Select superstars such as Radiohead and Nine Inch Nails can make previously unheard-of profits by cutting out the middlemen. The larger music business (as distinguished from the record industry) allows musicians and the people who work with them to make good money from concerts and licensing. But overall the music business has been very badly damaged, especially in the critical area of artist development, where literally thousands of jobs have been lost that cannot be easily replaced by cottage-industry efforts of artists and their managers.

Near the end of “Appetite for Self-Destruction,” Knopper suggests that record companies could fix themselves by hiring as bosses “digital music executives trained to build the next Napster.” That might be good advice for AOL (or it might not — AOL didn’t do so well when the company controlled Warner Music), but it makes no more sense for record companies than suggesting that book publishers could fix their business problems by marginalizing the power of editors and giving the reins to techies who would create the “next Kindle.”

Retailers such as Napster or, in a previous generation, Tower Records, are not and never were a replacement for risk-taking on individual artists. There have always been plenty of businesses that will market artists after they become successful and that make their decisions based on research of what is already popular. The particular role of record companies (or book publishers) has been to choose a few artists to support among hundreds of talented aspirants before they have a measurable sales base that justifies the risk. The nature of those positions invites criticism. When Bob Dylan’s debut album didn’t sell, he was famously called “Hammond’s folly” in the halls of CBS Records, a reference to John Hammond, who also took early risks on Billie Holiday and Bruce Springsteen. Technologists have many virtues, but replacing people like Hammond is not among them. And by the way, Hammond and his bosses were not the equivalent of Martin Luther King either.As someone who has made a living in the music business, it’s been hard for me not to be slightly amused by the outcry of newspaper writers and others who are anguished that the Internet has debased the concept of the value of content. I do not recall any Senate hearings lamenting the decline of record companies when it first became clear that they were being devastated by the same technological wave that was undermining the profitability of newspapers. I agree with most proposals to save journalism, including tax deductibility for trusts that publish, reasonable charges for content and moral suasion of consumers and elites. But I can’t help but wonder where they all were a few years ago when the record companies were slipping into decline.

It now appears that the record business, widely depicted at the time as being run by an anomalous group of greedy idiots, was more like the proverbial canary in the coal mine with regard to intellectual property and the Internet. Now that newspapers, magazines and movies are experiencing an erosion of value and the attendant job losses due to the increasing number of consumers who expect to get information and entertainment free, more people are considering whether the temporary huge profits of the Internet bubble may have had some adverse social consequences.

Newspaper and magazine publishers, perhaps influenced by the adverse publicity generated by record company battles, mostly acquiesced to the Internet theory that content should be free. They did not sue any readers; they did not develop elaborate encryption; they did not have spokespeople who argued with Internet providers or tech philosophers, and their Web-friendly behavior was no more effective than the confrontational posture the record companies had adopted. Publishers watched their assets decline just as precipitously as those of record companies, if not more. The theory that increased traffic generated by free content would create enough ancillary advertising revenue or promotional value has not proved to be true.

Frank Rich recently wrote in The New York Times, “With all due respect to show business, it’s only journalism that’s essential to a functioning democracy,” and I suppose he is right. But it’s a little like an argument about whether a human being would be better off without arms or without legs. Healthy societies need art, entertainment and journalism, and all these areas are affected by the technological revolution of recent years.

To the extent that there are solutions, they involve a post-’90s paradigm shift on the part of people and governments around the world in their view of all forms of intellectual property. Rich correctly points out that a lot depends on how much of the public is willing to pay for journalism. Commercial television was advertiser-supported and free to the public for decades until cable came along. Now most TV viewers pay a monthly fee for cable to get better reception and “free” channels like CNN. Millions pay additional fees for movie channels like HBO. But the development of subscription TV did not occur without help from the government, which offered local monopolies and other forms of support to cable companies.

One key step is a public and political recognition of the value of intellectual property. The out-of-context idea that “information wants to be free” has been destructive. Information doesn’t want to be free any more than land or food does. As individuals, we would like everything of value to be free, but as a society we have learned that nothing much gets produced if payment is based solely on philanthropy.

I don’t pretend to know the solution, but, as in many other areas of social policy, the United States can learn a lot from other countries. The governments of Canada, Sweden, Australia and many other nations subsidize portions of their music industries on the theory that music is good for society as a whole. There are proposals in Europe that would charge Internet service providers a fee for access to music. Undoubtedly there will be many other ideas that will emerge. One thing I am sure of — the answer is not a socioeconomic system in which the only money made from information goes to the makers of the machines that deliver it.

|

Danny Goldberg is president of Gold Village Entertainment and the author of “Bumping Into Geniuses: My Life Inside the Rock and Roll Business” (Gotham Books). |

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.