Daniel Berrigan Through the Eyes of a 1960s Ithaca Mom

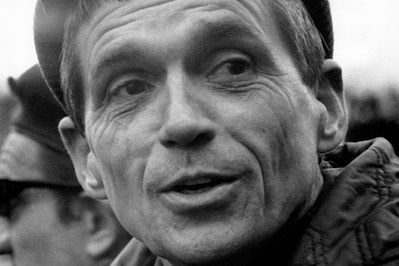

In our town and beyond, the priest, scholar, poet and activist served as a wake-up caller while the U.S. still had its eyes closed to the horrors of the Vietnam War. Rev. Daniel Berrigan speaks to anti-war demonstrators gathered in front of the U.S. Mission to the U.N. in New York City on Feb. 24, 1968. (AP)

1

2

Rev. Daniel Berrigan speaks to anti-war demonstrators gathered in front of the U.S. Mission to the U.N. in New York City on Feb. 24, 1968. (AP)

1

2

Rev. Daniel Berrigan speaks to anti-war demonstrators gathered in front of the U.S. Mission to the U.N. in New York City on Feb. 24, 1968. (AP)

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.