Critics, Monsters, Fanatics

In a new collection of her essays, Cynthia Ozick impresses us with flashes of brilliance but always seems to be mourning the magic, beauty and intellectual rigor of an earlier time.

“Critics, Monsters, Fanatics, & Other Literary Essays” A book by Cynthia Ozick

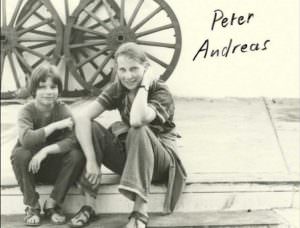

Eighty-eight-year-old Cynthia Ozick, whose intricate novels, short stories and essays have impressed us for decades, may have been born into the wrong century. She seems a creature of the past and somewhat out of place in the modern world. She is unfailingly polite but she is also aloof, occasionally defensive, and unaccustomed to the personal invasiveness that characterizes modern conversation. She offers cookies and other treats to her guests and shows off her grandmother’s candlesticks, but interviewers often leave frustrated.

Ozick grew up reading incessantly in a hammock behind her parent’s pharmacy in the Bronx. She had unusual confidence and although she knew her parents were struggling with surviving the Depression, she was lost in her own thoughts and dreams. Her literary hero was Henry James. She would mimic James, infusing his style with Yiddish-inflected rhythms in her own prose. She was not popular with the boys and whatever rebellion she felt was smothered under a desire to conform and please her parents. Ozick worshipped her mother and father with an uncritical adoration typical of her time. Her mother fussed over her, often bringing her plates of vanilla ice cream and cantaloupe.

In her new collection of essays, “Critics, Monsters, Fanatics, & Other Literary Essays,” Ozick impresses us with flashes of brilliance but always seems to be mourning the magic, beauty and intellectual rigor of an earlier time. She writes a biting commentary on the state of criticism, lacerating the majority of book critics and the magazines that publish them. She finds a few standouts. She admires Adam Kirsch, whom she sees as a modern day incarnation of her hero Lionel Trilling. She writes of Trilling that “no present-day magazine writer or blogger or reviewer or critic can aspire to what Trilling as essayist encompassed: his aim was nothing less than to define, and refine, civilization. He meant not only to comment or discriminate or analyze or judge, but to ‘stand’ for something.’ At his death at age seventy in 1975, what he finally stood for was a scrupulously perceptive and sinuously shaded interpretation of the moral life as expressed in the literature of the West. If the idea of sage could be applied to any American essayist after Emerson, that is what he had become. A more modulated perspective would settle for Trilling as the most discerning, the most reasoned, and certainly the most celebrated critic of his time.”

Ozick’s disappointment with the contemporary level of discourse is palpable. Some readers will undoubtedly agree with her assessment, but others, including this reviewer, may wonder if she is too old-fashioned and close-minded to recognize value in new forms of writing that fuse personal vision with politics, literature and history into their own unique vision. Contemporary writing is often more confessional in tone, spurred on by intense involvement in all forms of social media, and Ozick seems too quickly to dismiss these new channels.

Ozick does not shy away from making bold assertions about important issues in her new work. In one of the essays, she expresses her current thinking on the fictionalizing of the Holocaust. It is a practice that she abhors, while at the same time she confesses that she herself has been drawn to it. Her most famous work, the novella “The Shawl” (1989), tells of a woman whose child was murdered in a concentration camp. Thirty years later the woman is now living in Miami as a madwoman tormented by her past. One psychiatrist was so moved by “The Shawl” that he called to offer solace, convinced her fictional work was autobiographical.

In another interesting piece in this new collection, Ozick analyzes Rudolf Stach’s three-volume biography on Kafka, claiming Stach’s German heritage frees him from the baggage a Jewish writer might struggle with in trying to penetrate Kafka. She is impressed by Stach’s neutrality and his refusal to explain the inexplicable. She reflects on the struggle a modern biographer faces, writing:

“It is difficult to refrain from pondering how a biographer (and a biographer is inevitably also a historian) will confront these extremes of cultural tension. Every biography is, after all, a kind of autobiography; it reveals a predisposition, parallels, hidden needs: or possibly an unacknowledged wish to take on the subject’s persona, to become his secret sharer. The biographer’s choice of subject is a confession of more than interest or attunement. The desire to live alongside another life, year by year, thought by thought, is what we mean by possession.”

But while appreciating Ozick’s eloquence on the role of a biographer, the reader of this essay is left discouraged by Ozick’s resistance to share more deeply with us her own perceptions about Kafka. For example, she never touches upon how her Jewish identity and love of Western literature mirrors Kafka’s fractured loyalties as a German Jewish writer working in a time when anti-Semitism flared. Nor does she compare Kafka’s isolation to her own, particularly in her youth when she isolated herself in her childhood bedroom for years at a time, working on her first novel. This reticence characterizes almost all the essays in this collection, and leaves the reader hungry for an intimacy she doesn’t provide.But she once did allow her readers to come closer, and that writing sparkled with an energy, pathos and fearlessness that are missing here. In a series of revelatory pieces she wrote for The New Yorker we learn much about how Ozick became Ozick. There was one piece in particular that seemed strikingly different from all of her other work. Titled “Alfred Chester’s Wig,” it chronicles her intense friendship with a boy in her freshman writing class at New York University in 1946. He — Alfred Chester — was only 16, Ozick a year older. The professor pitted her and Chester against each other every week by having them read their pieces aloud to the class, after which the professor would decide who had bested whom. The other was left despondent. Instead of being divided, though, they forged a close bond and spent hours walking through bookstores in Greenwich Village, confiding to each other their fears and dreams. Ozick believed Chester to be the better writer, but thought herself superior intellectually. She was already learning German, Latin, history, and wanted a life that extended beyond the senses. He was different from anyone she had ever met: wild and unleashed, with homosexual tendencies she did not yet understand. He had lost all his hair from a rare childhood disease he never discussed with her, which left him completely bald. He wore a wig that rarely stayed in place. He tried to kiss her once but she pulled back nervously.

Their friendship began to fray as his charisma won him a following in the college cafeteria. She would sit among his other admirers listening to him hold court. He soon drifted off-campus to bars and parties. She was too timid to follow. He was the first boy to tell her that her too-wide nose wasn’t all that bad, and he always listened to her attentively. She loved him. But their friendship soon fractured when she questioned his declaration of homosexuality. Chester attacked her viciously for her innocence when it came to matters of the heart. Ozick’s narrative voice in this essay is exquisitely vulnerable and raw. She is unafraid to show us how much Chester hurt her, how much she missed him when they split up, and how she never really got over him. When she learns of his death decades later, she writes candidly: “I am certain as I can be of anything that I was never in Chester’s mind in the last decade of his life, but he was always in mine. He was a figure, a presence, a regret, a light, an ache. And no matter how remote he became, geographically or psychologically, he always retained the power to wound.”

In another confessional essay for The New Yorker called “Lovesickness,” Ozick reveals how she attended a friend’s wedding and instantaneously fell in love with the groom. It was an overwhelming infatuation that overtook her and she could not shake it. But she made no move to act on her emotions and she suffered silently pangs of unimaginable agony for months. But soon afterward, she recalls “a young man whose eyes were not green, who inspired nothing eccentric or adventurous, who never gave thought to brooks or lilies or death or transfiguration, who never sought to untangle the knots in the history of human thought, began, with awful consistency, to bring presents of marzipan. So much marzipan was making me sick-thought not lovesick.” This man became her husband.

Ozick’s personal essays for The New Yorker are very revealing. They show us a woman who was once tempted to live a wilder life, less constrained by domesticity, marriage and motherhood. A woman who flirted with trouncing convention, but ultimately felt too constrained to do so. In pictures of Ozick, we see a certain wildness in her eyes, a mischievous look that speaks to unfulfilled desires. But none of this emotional baggage is present in her new work of essays. We are left instead with her intellectual meanderings about our contemporary world. It is one that she clearly has a distinct distaste for.

Elaine Margolin is a freelance book critic whose work has appeared in numerous newspapers and literary journals including The Washington Post, San Francisco Chronicle, Jerusalem Post and Women’s Review of Books. She is based in New York.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.