Country, Smoothed Over

Ken Burns' documentary "Country Music" and its book tie-in present country music with a naive affection that misses key American tensions. Johnny Cash in 1972. (Heinrich Klaffs / Flickr)(CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Johnny Cash in 1972. (Heinrich Klaffs / Flickr)(CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A very good friend of mine, now deceased, interviewed Buck Owens back in the 1990s as the Buckaroo promoted his box set. My friend pitched Owens his favorite softball: “Hank or Lefty?” Owens, without blinking, shot back: “Merle.” In Ken Burns’ new 16-hour PBS documentary, “Country Music,” Merle Haggard muses fondly about the early 1950s, when every jukebox posed that weighty question to all honky-tonkers: Hank or Lefty, savior or sinner, martyr or scoundrel? The music’s gentle surface barely concealed its emotional sting.

Hank, Lefty … or Merle? It’s the kind of messy argument you won’t see or hear in this ambitious yet unremarkable PBS history, nor from the 560-page book tie-in Burns co-authors with Dayton Duncan. The clever way Owens lands on “Merle” won’t make any more sense after you read this book.

Click here to read long excerpts from “Country Music” at Google Books.

Burns’ film, like his others, has a masterful storytelling style that has made him a pillar of what we once called “public” television (if not its chief underwriter). The photographs, rare television footage and oral testimony gathered here will serve scholars and musicians for decades as a source of quotes: according to Rosanne Cash, Bob Dylan describes his first hearing of Johnny Cash as “Like a voice coming up through the center of the earth.” Willie Nelson sold vacuum cleaners before Faron Young cut his “Hello Walls,” and says, “I hawked my guitar so many times, the pawnbroker played it better than I did.” The sturdy timeline gets limned by the Carter family, Johnny and daughter Rosanne Cash, Brenda Lee, Merle Haggard (before his death in 2016), Loretta Lynn, and Dolly Parton. Burns pays particular attention to fierce female voices, like Wanda Jackson and Brenda Lee, pushing back hard against the style’s perceived misogyny.

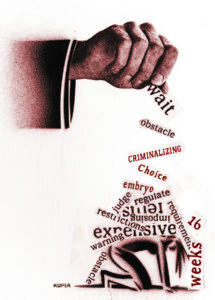

On the other hand, Burns and Duncan portray country music with such naive affection that you might never recognize it as expressing crucial American tensions between its prewar roots and the postwar sprawl, changing rural and urban worldviews, or the chasm between Southern and Northern myths. The cliches and platitudes that nearly wash out the music in this “respectable” frame belie the barbed yank of feeling these records capture. Hank Williams’ worried grin frames a hardscrabble dignity on his 1949 single, “My Bucket’s Got a Hole in It,” but Burns and Duncan leave such matters alone.

The handsome Knopf edition has all the inoffensive largesse of a prestige gift item. The pictures alone tell a deeper story than Duncan and Burns’ narrative, which leans hard on cliches and rarely rises above the encyclopedic. A mug shot of 19-year old Merle Haggard (A 45200) shows a wise man’s eyes burrowed inside the shock of a teenager’s face; Mel Tillis performs in front of a hundred shoe boxes piled up behind his eager band in a retail store; Ernest Tubb consoles Hank Williams’ mother Lilly at her son’s funeral on Jan. 4, 1953. So why do these authors feel compelled to add that this funeral saw the largest crowd gathered in Montgomery, Alabama, since the day Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as president of the Confederacy in 1861?

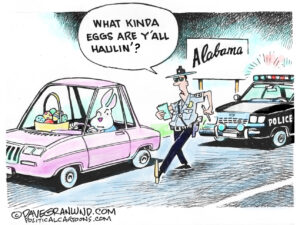

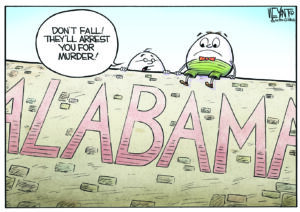

Like the Confederacy, the South prefers its musical history in platitudes (“Three chords and the truth”), much the same way it flies Confederate flags and defends Confederate statues into the 21st century without irony or remorse. That’s the same bland agenda that has made the dominant “white culture” such a tiresome trope in any history of America. And PBS has timed this launch as a punchline to Lil Nas X’s summer smart bomb, “Old Town Road,” which exploded country radio’s racism, then homophobia.

All the way through we get reminded, over and over, “Songs that tell stories, that’s country music …” as if no other musical style roots itself in story, or relies on narrative. Yes, story is crucial to Country, but that’s barely what makes it distinctive. (Did any editors on this project stop to think that Motown relies on story? Otis Redding? Aretha Franklin?) And that tiresome, meaningless phrase, “Three chords and the truth,” which Burns and Duncan ascribe to songwriter Harlan Howard… Holy Banality, Batman, didn’t Bono stamp that “Property of Rock Stars” back at some ’90s Rock Hall induction?

Burns and Duncan take pains to acknowledge the people of color who influenced major country figures, like Rufus “Tee Tot” Payne for Hank Williams, and Arnold Shultz for Johnny Cash. And in the early sequences of the film, Rhiannon Giddens explains how black sounds and experience couldn’t help but ferment white creativity. Burns carefully circles back to Wynton Marsalis to set up the Ray Charles 1962 lodestar, “Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music.” “We tend to think of it one way,” Marsalis argues. “White musicians listened to black musicians [on the radio]. Black musicians listened to white musicians too!” Burns frames this as an essential insight.

But Burns has already shown us that by 1962, when Charles recorded his Country sides, the entire American experience had been adjusting to how democratic (if still segregated) radio had become in comparison to the way people lived and moved through their everyday lives. The fantasy of integration filled the airwaves but not lived experience. When white audiences turned out for black performers, they still dined in separate restaurants and slept in different hotel rooms. In the Trump era, this kind of smoothing over the country’s racist wrinkles rings perversely tone-deaf. Does it ever occur to Burns or Duncan that Ray Charles may have appreciated a Country singer recording some of his material? Or have the Grand Ole Opry return the favor by inviting him to perform at the Ryman? When Richard Nixon attended the Opry as Watergate consumed his presidency in the summer of 1974, few mistook it as anything but a sap to his base, the Silent (White Southern) Majority that had reelected him in a landslide. Burns and Duncan say simply, “Nixon was happy to find a friendly audience.”

These careful omissions slip through all the rave reviews thrown at this material. Every time Burns and Duncan reference a person of color, it’s with the utmost respect. But Country music’s parade of celebrities has a White Only supertext. No protagonists carry any racial tint, and Charley Pride’s emergence in the mid-’60s as the style’s only person of color defines tokenism. According to Pride, his manager warned him that a star like Faron Young might “walk up to you and say, ‘You’re that N-word that’s trying to sing music.’ And I said, ‘Let’s go find him. We might as well get it over with right now.'” Pride befriended Young, an outspoken racist, as a way of ingratiating himself with Nashville’s elite. But even so, Pride’s early records withheld photos to conceal his skin color. Burns recounts this story as if it proves beyond a doubt that Country somehow snuffed out racism.

Or take the way Burns and Duncan recount how the more “respectable” styles, pop and jazz, heard Country. They highlight Tin Pan Alley crooner Tony Bennett’s huge hit in 1951 with Williams’ “Cold Cold Heart” without pointing out that it’s the only Williams song he ever touched, or that few other crooners went near the stuff, or how it signaled that the establishment pop songwriters were running out of yarn. In Burns and Duncan’s telling, Bennett lays on the hands of “respectable” (i.e., literate, European) tradition onto the sweet hillbilly hicks who accidentally stumbled into poetry; white trash gets “legitimized” by mainstream popsters. This ignores how much Bennett learned from Williams’ own interpretation of the song, and how he pushes the song away from Country (and how much the over-orchestrated record wilts). Does anybody in their right mind prefer Bennett’s high camp to Williams’ chafed lament?

Burns and Duncan don’t acknowledge this larger conflict between European (written) culture and American (oral folk) culture; it slips by without comment, making folk’s eventual dominance (alongside rock, soul, and rap) seem like a triumph without struggle.

This all fits with the Burns brand, a puppies and rainbows vision of America; he avoids tension even on volatile topics. His last piece, “The Vietnam War” (2017), featured contemporary testimony from communist military leaders and sympathizers. Contrasted with the many American veterans and reporters, it made for compelling footage.

That film presented only a single apology: from Nancy Biberman, a Columbia University student activist, who broke down in her regret at disrespecting a veteran. It’s an impassioned plea for acceptance and tolerance. But what kind of historian recounts the Vietnam epic only to land on a peacenik’s apology? All those old white, male Pentagon officials huff and puff and make their explanations for civilian massacres and chemical warfare and illegal secret bombing, but the apologies should come from the left—that’s what counts for balance in Burns’ sensibility. Historian Max Hastings handles it better in his masterful new history of the communists versus colonial powers, “Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy, 1945-1975”: “The war was such as neither side deserved to win.”

In those annoying Bank of America Twitter ads, Burns stars as the hero of his own documentary. He plays The Healer, the one who gathers up America’s stories, presenting the country to itself in its best light. When it comes to Country, he tries to make it all glow like Morning in America.

Tim Riley’s latest book is “What Goes On: The Beatles, Their Music, And Their Time.” He oversees the riley rock index, music’s metaportal, on the web.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.