Corporate Farmer Calls Upon Sen. Feinstein to Influence Environmental Dispute

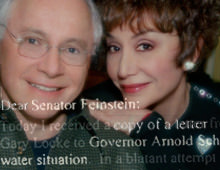

Wealthy corporate farmer Stewart Resnick (shown above with wife Lynda) has written check after check to U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein's campaigns, and when he needed her help, he got quick results.When wealthy donor Stewart Resnick asked for Dianne Feinstein's help, he got quick results.

By Lance Williams, California Watch

Wealthy corporate farmer Stewart Resnick has written check after check to U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s political campaigns. He’s hosted a party in her honor at his Beverly Hills mansion, and he’s entertained her at his second home in Aspen.

And in September, when Resnick asked Feinstein to weigh in on the side of agribusiness in a drought-fueled environmental dispute over the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, this wealthy grower and political donor got quick results, documents show.

On Sept. 4, Resnick wrote to Feinstein, complaining that the latest federal plan to rescue the delta’s endangered salmon and shad fisheries was “exacerbating the state’s severe drought” because it cut back on water available to irrigate crops. “Sloppy science” by federal wildlife agencies had led to “regulatory-induced water shortages,” he claimed.

“I really appreciate your involvement in this issue,” he wrote to Feinstein.

One week later, Feinstein forwarded Resnick’s letter to two U.S. Cabinet secretaries. In her own letter, she urged the administration to spend $750,000 for a sweeping re-examination of the science behind the entire delta environmental protection plan.

The Obama administration quickly agreed, authorizing another review of whether restrictions on pumping irrigation water were necessary to save the delta’s fish. The results could delay or change the course of the protection effort.

To environmentalists concerned with protecting the delta, it was a dispiriting display of the political clout wielded by Resnick, who is among California’s biggest growers and among its biggest political donors.

|

Click here to view an interactive graphic and documents related to this story. |

Resnick’s Paramount Farms owns 118,000 acres of heavily irrigated California orchards. And since he began buying farmland 25 years ago, Resnick, his wife and executives of his companies have donated $3.97 million to candidates and political committees, mostly in the Golden State, a California Watch review of public records shows.

They have given $29,000 to Feinstein and $246,000 more to Democratic political committees during years when she has sought re-election.

“It is very disappointing that one person can make this kind of request, and all of a sudden he has a senator on the phone, calling up [U.S. Interior Secretary Ken] Salazar,” says Jim Metropulos, senior advocate for the Sierra Club.

Feinstein’s letter was “based on what she believes to be the best policy for California and the nation,” Feinstein spokesman Gil Duran said in a statement. “No other factors play a role in her decisions.”

With the California Central Valley’s economy battered by recession and drought, Feinstein believed it was important to reconsider the restrictions on pumping delta water for irrigation, he said. Many farmers have urged such a review, he added.

In an interview, Resnick said he didn’t leverage his relationship with Feinstein to persuade her to intervene.

“Honestly, I’m not saying we could not have done that, but I don’t think that’s the way it happened,” he said. Feinstein long has had an interest in water issues, and “she just wanted to get to the bottom of this,” Resnick said.

A Troubled Estuary

The delta provides drinking water for 20 million people and irrigation for the state’s vast agriculture industry. But after decades of water diversions, delta fish populations are in catastrophic decline, scientists say.

Prodded by lawsuits from environmentalists, federal wildlife agencies commissioned scientific studies of the delta’s ecological crisis. Based on the studies, the agencies launched a restoration program that curtailed pumping for irrigation and increased water flows for migrating fish.

Meanwhile, three years of drought have forced big cuts in water allotments for farmers, and swaths of valley farmland lie fallow. The recession pushed the unemployment rate in some towns in the valley to 40 percent.

As a result, the restrictions on pumping delta water became the target of a series of noisy protests that played out over the summer. Farmers and politicians blamed “radical environmentalists” — and the Obama administration — for ignoring the drought’s impact on the valley’s economy. “The government decided that the farmers come second and the delta smelt come first,” as Sean Hannity of Fox News put it on a visit to Fresno.

Farm groups filed 13 different lawsuits to overturn the restoration plans, arguing that climate change, urbanization and discharges from sewers and factories are causing the delta’s problems. One suit was filed in August by the Coalition for a Sustainable Delta, a nonprofit founded by three executives of Resnick’s Paramount Farms. Resnick said he is “on the periphery” of the nonprofit.

People familiar with Resnick’s political operation say Feinstein’s letter is a reminder of the power he can wield on water issues.

“Paramount Farms is a huge player,” says Gerald Meral, former director of the Planning and Conservation League environmental lobby.

“They are just way different from the average farmer — far more strategic” in their thinking, Meral says.

Wealth and Philanthropy

In Los Angeles, Resnick, 72, is known as one of the city’s wealthiest men and among its most generous philanthropists. He’s given $55 million to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, millions more for a psychiatric hospital at UCLA and an energy institute at Cal Tech.

His wife and business partner, Lynda Resnick, is an entrepreneur, socialite and writer. Her 2008 marketing book, “Rubies in the Orchard,” attracted blurbs from Martha Stewart and Rupert Murdoch, and her “Ruby Tuesday” blog is sometimes featured on huffingtonpost.com. The couple live in a Beverly Hills mansion that writer Amy Wilentz called “Little Versailles.” It’s the scene of parties for celebrities, charities and politicians — governors, senators and presidential candidates.

Resnick said he worked his way through UCLA “washing windows,” and made his first million running a burglar alarm service. Since then, the couple’s Roll International holding company has profitably operated a long list of businesses: Teleflora florist wire service; POM Wonderful pomegranate juice; Franklin Mint, a mail-order collectibles firm; and FIJI bottled water, imported from the South Seas. Underpinning their fortune is agribusiness — 70,000 acres of pistachios and almonds, 48,000 acres of citrus and pomegranates — most of it in Kern County at the south end of the San Joaquin Valley, and all requiring irrigation to survive.

Resnick said he makes political donations “without much real strategy,” other than to give to centrists from both parties. Water issues aren’t a major factor, he said.

Records show Resnick often contributes to politicians with power over the bureaucracies that make decisions affecting farming’s financial bottom line.

Since 1993, the Resnicks have given $1.6 million to California governors, key players in determining state water policy. Their donation pattern seems nonpartisan, with the money following who’s in power.

In the 1990s, they gave $238,000 to Republican Gov. Pete Wilson, records show, although Resnick says he doesn’t recall giving to Wilson and doesn’t think he ever met him.

The Resnicks also backed the Democrat who replaced Wilson, Gray Davis. They gave Davis $643,000 and $91,500 more to oppose Davis’ recall in 2003.

With Davis gone, Resnick began donating to Arnold Schwarzenegger — $221,000, records show — plus $50,000 to a foundation that pays for the governor’s foreign travel.

Other big donations include $776,000 to Democratic political committees; $134,000 to agribusiness political committees and initiatives; and $59,000 to Republican committees.

Hedging Bets

The Resnicks have developed easy access to some of the politicians to whom they donate.

|

Click here to view an interactive graphic and documents related to this story. |

Schwarzenegger has called them “some of my dearest, dearest friends,” and like Feinstein, he has urged a review of the science behind the delta restoration plan. Davis appointed Resnick co-chair to a special state committee on water and agriculture.

A more enduring benefit came during Wilson’s administration, when Paramount Farms gained part ownership of what was to have been a state-owned storage bank for surplus water.

As recounted in a report by the advocacy group Public Citizen, in the 1980s state water officials devised a plan to ease the impact of future droughts by collecting excess water during rainy years and storing it underground.

The water was to be pumped south via the California Aqueduct, then put into a vast aquifer in Kern County that could hold a year’s water supply for 1 million homes. The state spent about $75 million to buy a 20,000-acre site and to design the water bank. But in 1994, state water officials transferred the water bank site to the local Kern County Water Agency in exchange for significant water rights, Resnick said. The water agency developed the water bank in partnership with four other public agencies and one private business — a subsidiary of Paramount Farms. Paramount wound up controlling a 48 percent share of the bank.

Resnick said the state had been unable to develop the water bank and gave up on the project. The local agencies and his company spent about $50 million to engineer the project and make the bank a success, he said.

Paramount’s control of the bank continues to infuriate some environmentalists. In recent dry years, the bank sold some of its stored water back to the state at a premium, Public Citizen reported.

“Resnick likes to call himself a farmer, but he is in the business of selling public water, with none of the profits returned to the taxpayers,” says Walter Shubin, a director of the Revive the San Joaquin environmental group in Fresno.

A Supportive Community

When she first emerged as a statewide candidate in the 1990 governor’s race, Feinstein made little headway in the Central Valley, and she was defeated by Wilson. After she was elected to the Senate two years later, Feinstein set out to befriend farmers.

Her attention to agriculture and water issues has paid off, says Dan Schnur, director of the Unruh Institute of Politics at USC and a former Wilson aide

“That community has been very supportive of her, much more for her than for most statewide Democrats,” Schnur says.

The Resnicks contributed $4,000 to Feinstein’s 1994 re-election campaign. When she ran again in 2000, they gave her $7,000. Resnick also donated $225,000 to Democratic political committees that were active in key Democratic races.

Resnick said he first got to know Feinstein personally 10 or 12 years ago because the senator also has a second home in Aspen.

In August 2000, when the Democratic National Convention was in Los Angeles, the Resnicks hosted a cocktail party for Feinstein in their home. Among the guests were the singer Nancy Sinatra, then-Gov. Davis and former President Jimmy Carter, the Los Angeles Times reported.

In 2007, they gave $10,000 to the Fund for the Majority, Feinstein’s political action committee. In June, another committee to which Resnick has contributed, the California Citrus Mutual PAC, spent $2,500 to host a fundraiser for Feinstein, records show.

Feinstein also socializes with the Resnicks. Arianna Huffington, the blog editor and former candidate for governor, told The New York Observer in 2006 that she had spent New Year’s with Feinstein at the Resnicks’ home in Aspen. “We wore silly hats and had lots of streamers and everything,” she said of the party.

On Aug. 26, Feinstein met with growers and water agency officials in Coalinga, Fresno County. While there, she told The Fresno Bee that she wanted the U.S. Interior Department to reconsider the biological opinions underlying the delta protection plan.

The following week, she received the letter from Resnick, which was first reported by the Contra Costa Times. She then sent her own letters to Interior Secretary Salazar and U.S. Commerce Secretary Gary Locke. Days later, the administration agreed to pay $750,000 to have the National Academy of Sciences restudy the scientific issues underlying the delta protection plan.

Last month, state lawmakers enacted a package of measures aimed at reforming the state’s outmoded water allocation system. The centerpiece — an $11 billion bond to build new dams and canals — must be approved by voters.

California Watch is a project of the Center for Investigative Reporting, with offices in the Bay Area and Sacramento.

This story was edited by Mark Katches and copy-edited by William Cooley at California Watch.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.