Community-Based ‘Bright Spots’ Offer Hope Against Climate Change

Scientists show how we can improve poor people’s lives by reversing practices that destroy the environment and fuel climate change.

By Richard Sadler / Climate News Network

Protecting the habitat of the orangutan is part of an initiative involving forest people in Indonesian Borneo. (Meret Signer via Flickr)

LONDON — We are constantly bombarded with bad news about climate change and the state of the planet — to the point where problems can seem so great that we feel powerless to do anything about them.

But an international group of scientists is seeking to change that by collating examples from around the world of “bright spots” — practical, community-based initiatives that enhance people’s health and wellbeing, while at the same time protecting their environment and benefiting the climate.

Over the last two years, researchers have analysed 100 of more than 500 such case studies submitted to the newly established Good Anthropocene website. They range from an initiative in Indonesia, in which forest people are offered healthcare in exchange for conserving natural resources, to a not-for-profit company in the Netherlands manufacturing modular, easily repairable mobile phones.

Human impact

Scientists from McGill University in Canada, Stockholm University in Sweden and Stellenbosch University in South Africa have studied some of the common factors behind successful projects. Their research, in a new paper titled Bright Spots: Seeds of a good Anthropocene, is published in the Ecological Society of America journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

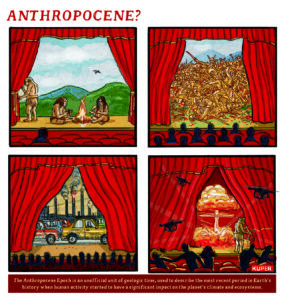

The term “Anthropocene” refers to the geological epoch that began when human activities first started to have a global impact on the Earth’s ecology.

The report notes that anthropogenic change is compromising the future of the biosphere — the area of the planet’s surface and atmosphere that supports all life — and threatening the planetary conditions necessary for human societies to flourish. However, it asserts that the future does not need to be bleak.

Among the initiatives highlighted are Health in Harmony, an award-winning project providing low-cost healthcare to marginalised communities in Indonesian Borneo in exchange for a commitment to protect natural resources and reduce deforestation.

Over the last five years, this has lead to a 68% reduction in illegal logging in Gunung Palung National Park, home to carbon-rich peat and one of the few remaining significant populations of orangutans. Over the same period, there has been a significant improvement in the general health of people living around the park.

Another success story is the Satoyama Project in Japan, which has helped revive traditional low-impact farming, where migration of wild animals can take place between ponds, rice paddies, grasslands and forests. City dwellers are collaborating with rural communities by staying on farms, carrying out voluntary manual work, offering financial support and helping to market eco-friendly products.

By contrast, Fairphone is a small Dutch non-profit company manufacturing mobile phones without using “conflict minerals” — materials mined in unstable parts of the world where human rights abuses are common.

The Fairphone is designed so that worn-out parts can be easily repaired or replaced, reducing the need for phones to be thrown away — and reducing demand for further mining of raw materials.

Big change

Lead author Dr Elena Bennett, associate professor at McGill University’s School of the Environment, thinks there is great potential for bright spots, or “seeds of good anthropocene”, to be replicated around the world.

“I’m excited about this project because it represents a big shift for environmental scientists to start looking at things positively,” she says. “We tend to be very focused on problems, so to look at examples of the sustainable solutions that people are coming up with — and to move towards asking ‘What do the solutions have in common? — is a big change.”

Dr Bennett adds: “This is also a move away from the typical academic perspective of looking at things in a top-down way, where we the scientists determine the definitions.

“We have encouraged people who are involved in the projects to define what makes a project ‘good’ — partly because we didn’t want to be driven by our northern European or North American sensibilities. We wanted to see a variety of ideas about what people want from the future.”

Richard Sadler, a former BBC environment correspondent, is a freelance environment and science journalist. He has written for various UK newspapers, including The Guardian, The Sunday Times and Ecologist.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.