Color Blind

Twelve years before Jackie Robinson began dismantling baseball's racial barriers, an integrated team of five whites and six blacks played in Bismarck, N.D., and went on to win the national semipro championship.Twelve years before Jackie Robinson began dismantling baseball's racial barriers, an integrated team of five whites and six blacks went on to win the national semipro championship.

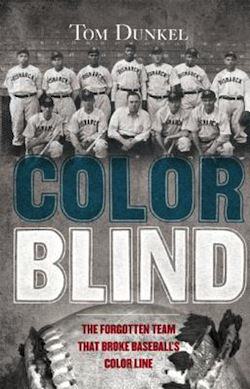

“Color Blind: The Forgotten Team That Broke Baseball’s Color Line” A book by Tom Dunkel

The cover photo for “Color Blind” shows an integrated baseball team, five white players and six blacks. One of the whites casually rests his hand on the shoulder of a black teammate. But the “B” on their caps does not stand for Boston or even Brooklyn. They played in Bismarck, the capital of North Dakota, and the photo dates to 1935, 12 years before Jackie Robinson started dismantling baseball’s racial barriers.

As told by Tom Dunkel, the story of how this team came to be — and won the national semipro championship — makes a delightful read. Baseball has deep roots in the dusty plains of the Dakotas. Gen. George Custer was based at Ft. Lincoln, just outside Bismarck, before losing a decisive road game to Sitting Bull and his Sioux All-Stars at the Little Big Horn in 1876. One of the 268 soldiers to die that day was Pvt. William Davis, third baseman for the post baseball team.

The major leagues assumed their current form in 1901, but in the decades that followed “the House of Baseball” (in historian Harold Seymour’s phrase) had many mansions. With no multiplexes or Netflixes to fill up leisure time, “industrial and recreational leagues flourished,” writes Dunkel, a freelance writer who lives in Washington, D.C. “Indian reservations had baseball teams. Employees of coal companies, trolley car manufacturers, police departments, funeral homes, and local Communist parties took to the field together in off-hours.” Baseball became the “weapon of choice for grudge matches between rival towns,” and Bismarck’s fiercest foe was Jamestown, 100 miles to the east.

After Jamestown started signing players from the Negro Leagues in 1932, Bismarck’s manager, an auto dealer and audacious gambler named Neil Churchill, wanted his own gang of “mercenaries.” He asked Abe Saperstein, a Chicago sports promoter best known for creating the Harlem Globetrotters, to recommend “the greatest colored pitcher in baseball today.” That’s easy, came the reply: Leroy “Satchel” Paige. In fact he’s probably “the best pitcher, period.” But you can’t get him, Saperstein insisted; he has a contract with the Pittsburgh Crawfords. I’ll try anyway, replied Churchill. Give me a contact number. Paige, it so happens, resented the owner of the Crawfords and “wanted out of Pittsburgh, the sooner the better.” For $300 or $400 a month plus a used Chrysler, Churchill “convinced baseball’s fastest gun to head west.”

It’s fair to say that Paige and his black teammates stood out in Bismarck. According to the 1930 census, there were exactly 377 “Negroes” in the entire state, and only 46 lived in the capital. The black players were barred from the city’s best hotels, and Churchill had to warn Paige not to be seen “riding white girls around in broad daylight.” But pitching is different from sleeping or dating. On Labor Day of 1933, almost 4,000 fans showed up to watch Satch strike out 15 Jamestown batters and drive in all three runs as Bismarck won 3 to 2. Vengeance was theirs.

Paige had an arm of high-tensile steel but “the heart of a wild stallion” and never stayed put for long. He skipped the entire 1934 season in Bismarck but returned the next year, perhaps because of Dorothy Running-Deer, whose father raised rattlesnakes and brewed a powerful anti-venom remedy based on a “secret Sioux recipe.” Satch “rubbed a few drops into his right biceps [and] nerve endings that he didn’t know he had screamed for relief.” But he became devoted to the stuff, kneading it into his muscles after every game and never suffering a sore arm. Good thing. When Bismarck swept to the semipro championship in Wichita that summer, Paige won four games, striking out 66 batters in 39 innings.

A triumph, yes, but with a bitter bite. Even though Paige made the majors in 1948, he was already in his 40s. During his best years, his brilliant talent was shadowed and suffocated by racism, and his black teammates played their whole careers in poorly paid obscurity. A major league scout who watched the games in Wichita lamented, “We wish we could find a chemical to bleach some of those colored boys. We could take some of those players up to the majors and win a pennant with ’em.” Paige said of the Bismarck squad: “That was the best team I ever saw. The best players I ever played with. But who ever heard of them?”

At times Dunkel tries too hard to be cute and comes off as annoying. “There is no big bang theory of baseball,” he writes, “It evolved like the blues and the miniskirt.” Really? Baseball is like a miniskirt? And calling Paige “the prize inside the Cracker Jack box of baseball” sounds more like a foul tip than a double off the wall.

Still this is a tale worth telling. As Satch said, no one has ever heard of that summer in Bismarck, when blacks and whites played and won together. Now they have.

Steven V. Roberts, who teaches journalism and politics at George Washington University, is writing a book about immigrant athletes.

©2013, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.