Clooney Mixes Social Issues With Classic Film Noir in ‘Suburbicon’

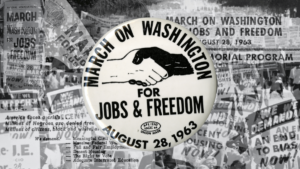

Outstanding performances and design elements are enough to make this entertaining effort by the movie star-director one to watch.The opening scene of “Suburbicon” is a travelogue introducing an idealistic, self-contained, suburban community of the 1950s. Called a melting pot of diversity, it includes white families from places as far-flung as New York and Ohio. Suburbicon is a fictional place modeled on nonfictional Levittown, Pa., of 1957 when a black family named Myers moved in and were harassed to a point that required intervention by state officials. Director George Clooney and his producing partner, Grant Heslov, were working on a screenplay about the incident when an old, unproduced script by the Coen brothers came across their desk, prompting them to fold one into the other.

After the opening sequence, the camera comes to rest on a mailman cheerily greeting each family while making his rounds. At the Mayers’ house, a black woman answers the door and is mistaken for a maid. When the mailman learns she is the lady of the house, he blanches, whispering at the next door, “Have you met your new neighbors?”

A meeting is convened among Suburbicon’s outraged white men who ironically “demand our civil rights to live where we want and with who we want. And with God’s help, we will overcome.” As the harassment begins, viewers familiar with Clooney the liberal activist might assume they are in for an astute satire of a seminal event in the civil rights movement that parallels our own racially fraught era. They would be wrong.

Most any Coen brothers screenplay, regardless of its tone and setting, is essentially film noir, and “Suburbicon” neatly fits the mold. It is not an astute study of a seminal event but an examination that finds nothing new in the hypocritical underbelly of the mostly Caucasian fantasy of postwar America. In a harsher review, Clooney and company might be accused of appropriating the African-American struggle to bring gravitas to an otherwise unrelated, though thoroughly enjoyable, plot centered on Gardner Lodge (Matt Damon) and his family, including his wheelchair-bound wife, Rose (Julianne Moore); her twin sister, Margaret (also Moore); and their little boy, Nicky (Noah Jupe).

When the family falls victim to a home invasion, Rose succumbs to an overdose of chloroform administered by a pair of typically Coen-esque characters, buffoonish and menacing criminals (Glenn Fleshler and Alex Hassell). Clooney’s canny directorial eye distinguishes the sequence by employing the conventions of the period—off-angle, static, single cuts building over Alexandre Desplat’s orchestrated dissonant strains. The score is one of the composer’s most accomplished efforts, even if there is too much of it.

Production designer James Bissell, nominated for “Good Night, and Good Luck,” adopts an appropriate mid-century aesthetic that Jenny Eagan accents with costumes derived from movies and ads of the era. The effect, though deliberately museum-like, is sumptuous.

Newcomer Noah Jupe, 13, has been blazing a path through television over the past two years and has no fewer than five movies coming out through 2018. He is the hero of “Suburbicon”: vulnerable, incorruptible and blessed with a natural curiosity that uncovers his father and aunt’s criminal plot, one that’s telegraphed a little too vividly.

As part of the grieving process, Lodge welcomes Aunt Margaret to come live with them. The murder-for-love-and-insurance-money scheme perfected by James M. Cain and turned into movies like “Double Indemnity” and “The Postman Always Rings Twice” is a hoary, old noir chestnut, so Clooney and company wisely emphasize the how of it rather than plot machinations.

And, oh yeah, racism. Nicky befriends Andy Mayers (Tony Espinosa), the besieged boy next door, and we are subjected again to images of the angry white mob lashing out as the family maintains a dignified silence.

And now back again to murder and mayhem at Nicky’s house.

Transitions occur that abruptly.

Even worse, the two stories do not cross over at any point. This is the movie’s biggest failing.

Luckily, it’s not enough to torpedo Clooney’s entertaining thriller that features another committed performance from a double-chinned Damon, who internalizes a not-fully-convincing transition from sociopath to blood-soaked killer. Nevertheless, the effect is visceral, mostly in the early going when he’s not pedaling a tricycle away from an exploding vehicle.

Yes, there are occasional tonal issues, another minor shortcoming in the face of many strengths—like Moore’s chirpy and likewise ethically challenged Margaret. An Oscar winner and frequent Todd Haynes collaborator, Moore seems incapable of a false move, regardless of the caliber of the movie around her.

Yet even Oscar Isaac upstages her, when he stops in for two scenes as an insurance claims investigator who can smell a rat in a rose garden. The writing, directing and acting in this lengthy exchange is one of the movie’s high points. Visually, only watching Nicky trapped under the bed with a knife-wielding attacker coming for him outdoes it. The scene is a primal childhood nightmare made real by cinematographer Robert Elswit’s evocative compositions and Stephen Mirrione’s precisely timed edits.

Throughout his directing career, Clooney has taken a stab at various classical genres. “Leatherheads” is his attempt at a Gable-and-Lombard screwball comedy; “Good Night, and Good Luck,” his 1950s political thriller; “The Monuments Men,” a World War II picture, albeit one where hard-charging infantryman are traded for helmeted art nerds facing off against Nazis. They seem to be part of his process—learning the language of each genre to learn the language of all.

His stab at film noir, “Suburbicon,” is not cinematically earth shattering, and it won’t inspire conversation on race relations. Hell, it won’t even inspire conversations on family relations. But when it works, it’s outstanding. And when it doesn’t, it’s good enough.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.