Climate Change Linked to Reduced Size of Alpine Chamois

Scientists have found strong evidence that declining body size in herds of the chamois mountain goats that are hunted in the Italian Alps is linked to warmer spring and summer temperatures.

By Tim Radford, Climate News Network

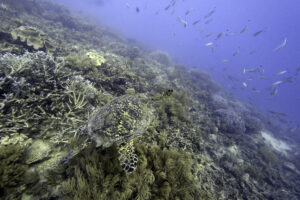

A herd of chamois mountain goats foraging for food in an Alpine meadow. Photo by Svetovid via Wikimedia Commons

This piece first appeared at Climate News Network.

LONDON — The Alpine chamois is getting smaller. Researchers have found that climate change and a gradual rise in average temperatures over the last 35 years mean that young chamois now weigh about 25% less than animals of the same age did in the 1980s.

The latest find, reported in Frontiers in Zoology, is yet more evidence that bodymass and climatic conditions are linked, and that mammals have a tendency to respond to rising temperatures by dwindling in size.

“Body size declines attributed to climate change are widespread in the animal kingdom, with many fish, bird and animal species getting smaller,” said Tom Mason, a biologist at Durham University in the UK. “However, the decreases we observe here are astonishing. The impact on chamois weight could pose real problems for the survival of these populations.”

Vital statistics

Chamois, a mountain goat-antelope species native to Europe, are hunted every autumn in the Italian Alps — under strict regulation, which has allowed populations to increase. So the researchers had access to the vital statistics of more than 10,000 yearling chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra) shot between 1979 and 2010 in three hunting districts in the mountains of Trento province in northern Italy.

The researchers found “clear negative temporal body mass trends in all sexes and sites” in all three populations.

In cold conditions, higher body mass confers advantage. Bigger animals will have a lower ratio of skin to volume, and therefore conserve warmth more easily. Conversely, in the tropics, smaller creatures have a greater ratio of surface through which they can radiate heat, and more easily maintain thermal equilibrium.

Biologists have confirmed this effect in fossil records: skeletal evidence shows that ancestral horses, deer and primates all got smaller as temperatures soared during a dramatic hot spell 55 million years ago. And they have found tentative evidence in a long study of the weights of America’s wild bison across a range of prairie temperatures.

Scientists have also warned that to survive dramatic global warming, humans could shrink to almost Hobbit-like dimensions.

The Alpine studies establish that the lower bodyweights of the chamois native to the region are linked to temperature, rather than to the availability of food.

Levels of nourishment

The same long-term data records reveal that the Alpine meadows that feed these mountain goats are just as productive, and deliver the same levels of nourishment, as they did four decades ago. But Alpine temperatures on average became between 3°C and 4°C warmer over the same period.

“We know that chamois cope with hot periods by resting more and spending less time searching for food, and this may be restricting their size more than the quality of the vegetation they eat,” said Stephen Willis, a co-author. “If climate change results in similar behavioural and body mass changes in domestic livestock, this could have impacts on agricultural productivity in coming decades.”

Wild animals are anyway under pressure from human population growth and loss of habitat, but the latest findings present new puzzles.

Body mass is valuable: it gets a grazing animal through the harshest winters. So chamois numbers are likely to fall, or may have to be kept low.

Dr Mason said: “This study shows the striking, unforeseen impacts that climate change can have on animal populations.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.