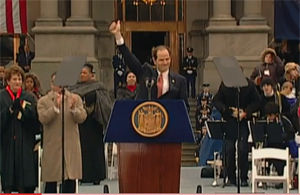

‘Client 9’: The Rehabilitation of Eliot Spitzer

A confession: I’ve never liked Eliot Spitzer He has his virtues: He is relentlessly—and not stupidly—articulate He has the right enemies, be they corporate titans or the endemically corrupt denizens of the New York legislature He is natty in his well-cut suits (by Hickey-Freeman, as the New York Times informs us) .

A confession: I’ve never liked Eliot Spitzer.

He has his virtues: He is relentlessly—and not stupidly—articulate. He has the right enemies, be they corporate titans or the endemically corrupt denizens of the New York Legislature. He is natty in his well-cut suits (by Hickey-Freeman, as The New York Times informs us). He has borne his recent public humiliations stoically, and he has managed his flank-speed rehabilitation cannily. It’s hard to think of anyone else in American public life who has gone from the governorship of a major state to whore hound to a nightly TV gig on a political gabfest in less than three years, all without explanation, let alone meaningful apology.

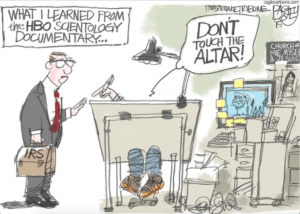

But still. … There was always too much righteous glee when he was having his troops lead Wall Street’s white-collar criminals out of their offices in handcuffs, too much contempt and arrogance in his treatment of Albany’s lawmakers and lawbreakers, who come off in Alex Gibney’s rather curious documentary “Client Nine: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer” as characters in a particularly unfunny community theater production of “Guys and Dolls.” The picture has its virtues, especially in its examination of how a high-priced “escort” service—upon which Spitzer dropped $100,000 in fees over the years—goes about its business. You will perhaps not be surprised to learn that its work force by and large present themselves as Happy Hookers. You will perhaps be somewhat astonished to learn that Spitzer quite literally sees his demise as a Greek tragedy; the word hubris is frequently used to identify his “tragic” flaw—other details not forthcoming.

With good reason, it seems to me. Spitzer apparently thinks of himself in aristocratic, if not noble, terms. He is wealthy, he’s been to all the best schools (Princeton, Harvard Law) and he talks in well-turned paragraphs. But his money is recent—made by his apparently chilly father in ignoble New York real estate—and Ivy League educations (which include learning to talk good) are by no means reserved to the chinless progeny of the East Coast elite. A bright guy can learn to walk that walk and talk that talk almost by osmosis. And with no particular need to earn a living, the ideal of “public service” presents itself attractively to such a figure. It is the one idea that was not available to Jay Gatsby, who, far more than Oedipus, is the analogy we should be reaching for in this case.

Put simply, it takes more than a generation to rub the rough edges off an arriviste and make him fit for public life (in the case of the Rockefeller brothers, who pioneered this form of social service, it required three). Spitzer was still too close to his father’s rough-and-tumble beginnings to acquire the airs and graces requisite for hypocritical public life. This failing accounts for his go-for-the-throat pursuit of miscreants. And, probably, for his low-life sexual predilections.

I mean, really, ample precedents—see, again, the Rockefeller model—are available. In particular, we are speaking now of the discreet mistress, handily situated in a family-owned apartment. Or, somewhat less elegantly (and more cost-efficient), the gaga campaign worker, just down the hall in the Oswego motel. It appears to me that what undid Spitzer was more than anything else—how to put this?—lack of taste. And, of course, lack of common sense. It was just too easy for his enemies to follow the money he expended in pursuit of his pleasures.

We are, naturally, free to speculate on why Spitzer chose the course that he did. We commonly believe that men who resort to prostitutes are in some way emotionally stunted, incapable of authentic intimacy, and one suspects, merely from watching Spitzer’s performance before Gibney’s cameras, that that’s the case. Beyond that, you have to wonder if Spitzer ever calculated the fallout should his activities be revealed. Having an affair implies, at least, that passion, however careless or misguided, might have been a factor in the relationship. But sex for cash, especially on a long-term basis, is pathetic—especially in the case of the well-favored. You can’t help but snicker at it, especially when the john is a loudmouthed holier-than-thou type.

Then there is the matter of his wife to consider. We see her in two modes—as a pretty, personable woman cheerfully campaigning with her husband and reveling in his electoral triumph. But we also see her gray and haggard countenance as she stand by her man—the perfect perp spouse—as he announces his resignation. If there is really a tragedy in this story, it belongs to “The Good Wife,” and though one scarcely expects to see an interview with her, I think “The Bad Husband” should be made to answer for her pain in some more than ritualistic way.

In general, I don’t believe that sexual conduct, however weird, necessarily harms one’s ability to conduct business in a perfectly rational manner. It’s just a matter of keeping the compartments watertight. But in this instance, you have to wonder—especially since Spitzer is never pressed by Gibney to go beyond the hubris explanation.

I can sympathize with the filmmaker. I wouldn’t want to be the one asking the hard questions in this context. But the result is an unsatisfactory film. One emerges from it feeling that it is an incident in the rehabilitation of a reputation, rather than a document that probes the sources of really stupid and self-destructive behavior. Eliot Spitzer is a great “get” for any reporter, but the get has got to give more than he does here. It may be that he has at last found his true métier—as a talking head on cable. But I wouldn’t count on it.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.