‘Civilizing’ Perpetual Foreigners

In a time rife with anti-immigrant invective, Truthdig reviews a book that explores a historic episode involving missionaries and migrant Chinese women. Knopf

Knopf

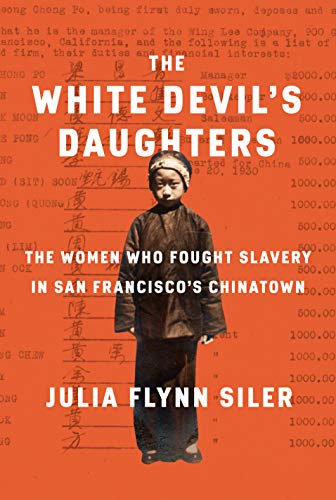

“The White Devil’s Daughters: The Women Who Fought Slavery in San Francisco’s Chinatown”

A book by Julia Flynn Siler

The horrendous experiences of Chinese immigrant women and children who were smuggled into prostitution and child slavery in the United States during the late 1800s are, for the most part, widely unknown. Julia Flynn Siler’s book on the subject, “The White Devil’s Daughters: The Women Who Fought Slavery in San Francisco’s Chinatown,” begins promisingly: “A ghost story led me to the edge of Chinatown. On a crisp morning in 2013, I dodged the crowds in Union Square and walked past a pair of stone lions up a hill. I had an address—920 Sacramento Street—and a description. I was looking for a five-story structure built with misshapen red bricks—some salvaged from the earthquakes and firestorms that razed most of the city in 1906.” But the allure of her introduction almost immediately evaporates into a litany of horror stories told without empathy.

Siler’s central story circles the lives of two women who enjoyed an intense friendship that endured for over half a century. One was Donaldina Cameron, whose life work was as a Christian missionary in San Francisco, rescuing Chinese prostitutes and child slaves brought from China and thrown into lives of unspeakable terror. The other woman was Cameron’s assistant, Tien Fu Wu, a former household slave sold by her father to pay his gambling debts. The women and children Cameron and Wu worked to save were usually stolen or sold by their fathers, a practice not outlawed in China until 1928. Prostitution was not illegal in the United States at this time. The smugglers often held auctions of Chinese women openly on the docks. As San Francisco began to lose some of its roughness and more white women began to settle there, these meat market auctions were moved to private locations.

The feats attempted by these two women were spectacular. Cameron and Wu often tangled with the police who frequently stood to benefit from the trafficking, fought the courts for custody of the rescued women and girls, and were continually threatened by the Chinese “tongs,” gangs of violent underworld thugs who ran human trafficking rings while warring over territory and power.

Once the women and girls were safely ensconced in the Mission House under Cameron and Wu’s care, they were taught to read and write English, and to cook and sew. Bible study was an important part of each day, as was preparing to be baptized. Most of the women were being trained as competent homemakers. A few made it to college. One became a doctor and another a nurse. Yet another married Poon Chew, the editor of the first Chinese daily newspaper in the United States. Cameron and Wu rescued over 3,000 women and girls. But these were the exceptions.

Click here to read long excerpts from “The White Devil’s Daughter” at Google Books.

Siler presents Cameron without any embarrassment as a white messiah figure. Siler does not flesh out Cameron or Wu; they remain elusive heroic figures.

Yet she reveals a side of Cameron rife with ethnocentrism and elitism. At one point, Cameron suffered a nervous breakdown, but returned to work shortly afterward. Siler writes, “She must have wondered, in her darker moments, whether the cause she’d devoted her life to was truly worth the cost. … More troubling were the indications that some, if not many, of the subjects of her rescue efforts were not interested in her help. The invective hurled at her suggested that some—or perhaps many—of the ‘Chinese slave girls’ that she and her supporters had hoped to save had no desire to become Christians.” Siler records another troubling incident when the Chinese girls found a dead bird and decided to bury it according to their own customs based on Chinese folk beliefs.

But Siler ignores the psychological costs of intentionally erasing Chinese culture and belief systems. Nor does she examine the missionaries’ presumption that it was within their rights to convert their charges to Christianity to “civilize” them. Siler never considers the additional trauma to these woman and children that such a rupture would cause. This attempt to mold them into Christians might be perceived as another form of rape, though Siler and Cameron would surely balk at such an assertion.

Siler cleverly intersperses her narrative with haunting pictures of dark, narrow streets filled with sinister looking Chinese men, and terrified shots of Chinese women prostitutes peeking out of small windows. These photographs are juxtaposed with snapshots of Cameron, a dignified, slender, tall white woman with a beatific smile, usually holding the hand of one of the Chinese babies she has rescued. Wu looks serious and attentive, the scars of her past life still visible. The photographs of Cameron affirm Siler’s assessment of Cameron as an exemplary figure beyond reproach.

Siler outlines the laws against Chinese immigrants, which grew more extreme with time. The Chinese were banned from carrying vegetables and laundry on a pole as was their custom. Their children could not attend public school. The single long braid worn by Chinese men down their backs was shorn off. In 1893, a Chinese immigrant could be stopped anywhere and asked to show their residency papers. The Chinese were not allowed to have relations with whites. They could not testify in court. They could not work for the government. The Exclusion Act of 1882 banned any Chinese from coming to America, and this law was not rescinded for many decades. There were spontaneous violent assaults on Chinese immigrants. The worst was in 1871, when 17 Chinese men were murdered by a lynch mob of white men in Los Angeles. Similar laws would be cast upon the Jews decades later in Germany as the Jewish annihilation began.

Chinese men, as most people know, had come to America and built the railroads, labored in mines, and planted and harvested crops. Many worked as house servants. But their contributions did nothing to change the dominant perception of them as alien and treacherous. Many Americans thought them to be filthy, barbaric, spiritless, and reminiscent of automatons.

And here Siler misses a very important opportunity. She has no curiosity about how these pernicious attitudes toward the Chinese were conceived and propagated and clung to, even into our own time.

Contemporary Vietnamese author Viet Thanh Nguyen has said that he refuses to defend Asian humanity because as Toni Morrison says in “Beloved,” once you attempt to explain yourself to white people, it “distorts you because you start from a position of assuming your inhumanity or lack of humanity in other people’s eyes. …” Karan Mahajan has written that Asians are still seen as “perpetual foreigners at worst, or probationary Americans at best.”

But Siler seems oblivious to an entire community’s feelings of hopelessness and denigration. She writes from the entitled position of white privileged power, which sees only what it wishes to. And it is this blindness and lack of empathy that mar her book. One senses she has never truly experienced powerlessness or the desperation felt by San Franciscan Chinese Consul-General Huang Zunxian when he wrote these words in 1885 during a peak of anti-Chinese violence:

Men are no longer regarded as men here

Mauled like a subhuman species

In this vast and desolate world

Where can they find a foothold?

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.