‘Citizen Jane’: A Hugely Entertaining Film Oversimplifies the 1950s Battle Over Growth in New York

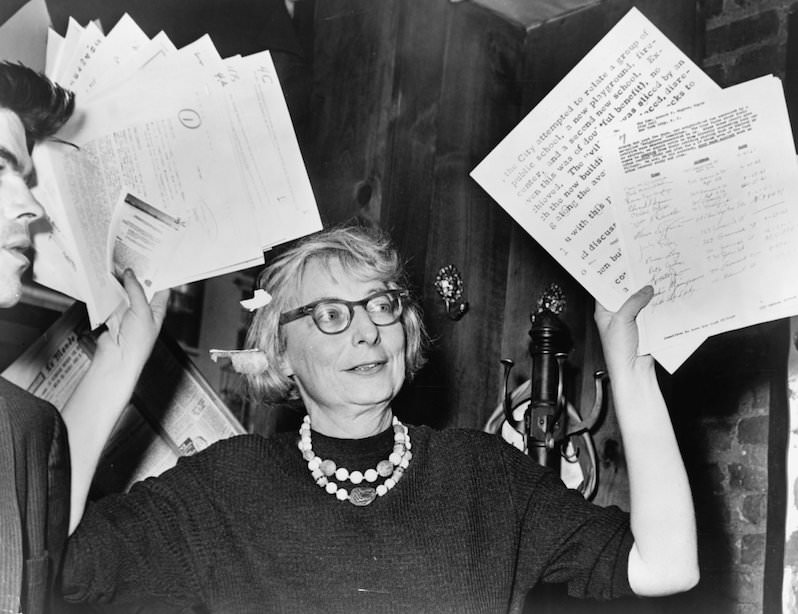

Matt Tyrnauer’s chronicle also fails to connect the dots between the issues that beset America’s largest city in 1957 and those facing urban centers today. (Pictured, Jane Jacobs.) Good "Citizen": Jane Jacobs enjoys a triumph in this still from Matt Tyrnauer's urban development documentary, "Citizen Jane." (IMDb)

Good "Citizen": Jane Jacobs enjoys a triumph in this still from Matt Tyrnauer's urban development documentary, "Citizen Jane." (IMDb)

At a time when mega-cities of 20 million to 30 million are mushrooming around the globe, what can citizens and planners learn from the New York City of the 1950s, when it had a population of 8 million?

“Citizen Jane: Battle for the City,” Matt Tyrnauer’s lively chronicle, recalls the successive faceoffs between Jane Jacobs, street-level activist and urban theorist, and Robert Moses, who by the middle of the century was an imperious city planner. As a David and Goliath story, the film is hugely entertaining. As a planning primer for today, when the scale and speed of global urbanization is unprecedented in human history, “Citizen Jane” oversimplifies its protagonist and antagonist. To paraphrase the title of Jacobs’ historic book, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” Tyrnauer’s “Citizen Jane” should be called, quite bluntly, “The Fall of Moses and Rise of Jacobs.”

In 1955, when the car-friendly Moses proposed to bisect Washington Square Park with an extension of Fifth Avenue, and again in 1962, when he planned a crosstown expressway connecting the Holland Tunnel with the Williamsburg Bridge, Jacobs mobilized protesters against those actions. (Moses dismissed the first group as only “a bunch of mothers.”) Jacobs’ resistance helped preserve the integrity of Greenwich Village, Chinatown and Little Italy and made possible the adaptive reuse of factory neighborhoods that became SoHo and TriBeCa.

It’s undeniably satisfying to see the rumpled Jacobs, boasting a [Norman] Mailer for Mayor button, symbolically stand between the master builder and the bulldozers. Yet the filmmakers don’t connect the dots between the issues that beset America’s largest city in 1957 and those facing far more populous urban centers 60 years later.

More’s the pity, because the filmmakers have on tap a brain trust of historians, planners and observers who are more than up to the job. Among them are historian Mike Davis (“City of Quartz”), architecture critic Paul Goldberger and architect-planner Michael Sorkin. They could have explained that keeping cities vital is about more than simply preserving the urban fabric that Jacobs fought for and opposing the top-down planning that Moses prescribed.

In historic footage in which Moses slates tenement neighborhoods for demolition and displaces longtime residents, he insists that he is just carving the cancer from the city. It’s easy to hear “cancer” as a code for “poor” or “nonwhite.” In league with developers, Moses replaced the so-called chaos of some neighborhoods with the presumed order of high-rise “projects.” These resulted in concentrating poverty in a handful of buildings, blocking the ability of tenants to look out at street life.

Tyrnauer’s film jumps from the failed New York projects of the 1950s to images of similar-looking high-rises being built today in rapidly urbanizing China. We are advised by a talking head that “China is Moses on steroids,” suggesting that planners there have not learned from New York of the mid-20th century. But New York in 1957 is not exactly parallel with China in 2017. One is a historic city where changes are made to adapt it to new uses. The other often involves building new metropolises from the ground up.

The takeaway is that Jacobs was entirely right and Moses entirely wrong. It would be more accurate to say that Jacobs championed neighborhoods built on a human scale and served by mass transit, and that after World War II, Moses believed the future belonged to higher-density architecture, superblocks and private automobiles. It also would be accurate to say that for better or worse, New York City, like many metropolises, accommodates pedestrians, bicyclists and automobiles in high-density and low-density neighborhoods. It’s not an either/or proposition. Don’t all cities, especially those built from the ground up, have to combine elements of Jacobs’ concerns with views advocated by Moses?

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.