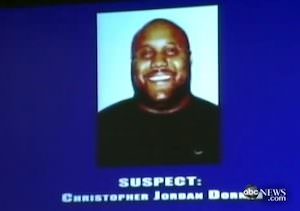

Christopher Dorner and the Lines That Divide Us

Issues of race and the LAPD have been raised once again in the case of Christopher Dorner, a dismissed African-American cop accused of killing four people before apparently losing his life in a gunfight with police and subsequent fire.Issues of race and the LAPD have been raised once again in the case of Christopher Dorner, a dismissed African-American cop accused of killing four people.

Fault lines of class, gender, generation, geography and race split society, observed the late newspaper editor Robert Maynard. The racial division, clear almost two decades ago during the O.J. Simpson murder trial, has emerged again in the public discourse over the case of Christopher Dorner, a dismissed African-American cop accused of killing four people before apparently losing his life in a gunfight with police and subsequent fire.

Maynard, who was also African-American, was editor and publisher of The Oakland Tribune and co-founder of the Institute for Journalism Education. His fault line theory was inspired by the earthquake faults that underlie California and the societal faults that periodically rip the nation, his state and his city of Oakland.

Maynard conceived his theory as a way of teaching journalists how to cover diverse and volatile communities. “The society is split along five faults, and we try in vain to paper them over, fill them in or pretend they aren’t there,” Maynard said.

Having been one of the institute’s instructors, I thought the fault line theory went beyond journalism and was a good way to describe how all people look upon social differences. My understanding was buttressed by my experience covering the Simpson trial. During those proceedings, televised nationally every day, Americans divided, often along racial lines, over whether the former actor and athlete was guilty of murder or was being framed by the Los Angeles Police Department.

Underscoring the latter belief were years of police abuse in L.A.’s African-American and Latino neighborhoods, a story repeated in cities across the country. Abuse was particularly bad in South Los Angeles where many generations of families have told stories of young men being falsely arrested, beaten or stopped for no reason by the LAPD. These sentiments helped feed the fury of the city’s 1965 and 1992 riots.

In his manifesto, posted on his Facebook page, Dorner said he was driven from the LAPD when he reported that his white training officer had kicked a homeless man. Instead of listening to him, he said, racist department officials disciplined him, taking him before a Board of Rights, consisting of two police officers and a lawyer. In the end, Dorner was fired and he left the LAPD enraged, believing the fix was in.

Taking revenge, law enforcement officers said, Dorner shot to death the daughter of his Board of Rights defense attorney (a former police captain) and her fiance. As he fled eastward, authorities say he killed a police officer in Riverside and a sheriff’s deputy during his final stand in the mountains.

Although reaction to the Dorner matter has not been nearly as intense as the inflamed emotions touched off by the Simpson case, I see some similarities. Sandy Banks, who is African-American, captured the feelings in her Los Angeles Times column:

“Is this the story of one paranoid, delusional man with a long memory, a mean streak and a murderous vendetta?

“Or is it a reflection of racism, callousness and corruption, still stubbornly embedded in our new-and-improved Los Angeles Police Department?”

Questions such as these, raised by an experienced journalist and by others elsewhere, prompted LAPD Chief Charlie Beck to speak out in an unusual interview. Beck and his predecessor, William Bratton, had changed the department from one that policed the city in the manner of an occupying army to an organization more reflective of a diverse metropolis, and Beck is proud of the accomplishment.

The chief’s interview was with Pat Harvey, a veteran African-American anchor for the combined news operations of television stations KCBS and KCAL. Beck talked of his plans to re-examine Dorner’s treatment by the department, including the Board of Rights hearing. “I want you to know and your viewers to know that I am not doing this to appease him,” he said. “I am doing this so the community has faith in what the police department does. And I am going to make a rigorous inspection to either validate or refute his claims and we will make [it] public.”

Then Harvey posed a question that delved even deeper into Beck’s worries about the Dorner situation. “Why did you choose me to do this interview?” she asked. “You and I have a good relationship and I think you are someone people respect as a journalist,” Beck replied. “You are also somebody the African-American community respects and part of this message is for that community because of Dorner’s allegations about a police department that doesn’t treat African-Americans fairly and I don’t think that’s true and I want to make sure we don’t lose the precious ground we’ve gained. …”

Certainly this isn’t the same country as it was before the election of our first black president. Yet despite Barack Obama’s substantial re-election victory, the 2012 campaign was riddled with poisonous references to class, gender and race, and it revealed geographical divisions as well.

These are Robert Maynard’s fault lines. The existence of one of them — race — and the knowledge of the harm it has done to his community was the reason for the white police chief’s interview with the African-American anchor. It’s a move that should be noticed by leaders in other American racial hot spots.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.