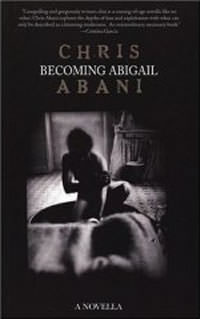

Chris Abani: Abigail and My Becoming

The acclaimed Nigerian novelist recounts the origins of his harrowing new novella about child prostitution "The third-fastest-growing industry, after arms and drugs, is the trafficking of young women for sex You won't find it listed on the GDP or GNP of any nation Everyone pretends that it doesn't happen" Also, read in an interview how Abani's imprisonment and torture informed his writing .

Editor’s Note

: The following is an original essay by Chris Abani on the origins of his new novella “Becoming Abigail.” Click here to jump straight to the full-text version of the first four chapters of the book. Click here to jump to his interview with Truthdig. (See the sidebar below and to the right for more information.)

. . . Hence she was unintended worship, a minute of possibilities as he wanders in what seemed to be streets and alleys ??Unintended Worship,? Adonis

This is how ghosts inhabit you; haunt you until you respond to them. There is not deep fiction without ghosts. Without deep haunting, duende is nothing more than Britney Spears dancing to another asinine song.

*

Reading the roots of history heading towards a woman ??Unintended Worship,? Adonis

*

So. It is 1996 in London. Winter. I remember snow, so it was winter. There on the news was the pulped face of a young black girl. Nigerian. Brought over by relatives to be a domestic. Her bloody face was the result of an attempt to discipline her, presumably for some slight. I remembered that one eye was closed over completely like she had gone several rounds with Tyson in the ring. The other, a little lazy, stared in confusion at the camera. One eye closed in on another world, like Odin hanging from the world tree. The other as startled as a young doe. Even in that moment, I must have thought of Blake. But then I write fiction. So I may be lying. I couldn’t bear her stare so I changed the channel. ?Babylon 5? was on. Great.

*

A few months later, waiting for my friend at the South Bank Center, sitting by a big window overlooking the Thames, nursing a tea and flipping through an old newspaper someone had discarded, a story caught my eye. A judge in France presiding over an immigration case fell in love with a young woman brought before him. She was fleeing some injustice to women in Morocco. Anyway, she was underage and he was forced to retire. The full nature of their relationship was not clear. The girl tried to appeal his dismissal. Then she appealed the order keeping them apart. She was in love. Finally, with some misguided notion that if she were not around everything would go back to normal for him, she killed herself.

*

Are you part of my abyss, of my upheaval ??Unintended Worship,? Adonis

*

Did I mention that deep song comes from haunting? I did? Forgive me.

*

An old lover once asked me if I would die for her. I couldn’t say, Of course not, are you crazy? Not when the room was bathed in candlelight. Not when Coleman Hawkins was on the stereo. Not when she had made her daughter go stay with a friend. Not in that moment, London falling away in lights from the window of her high-rise council flat.

Instead, I pointed out the window, at a flickering train in the darkness, and said: ?Can you wish on a train moving through rain and night??

?Coward!? And even as she said this, I was already leaving on that train. There would be other nights and other trains, but this one was lost.

*

Ghosts leave their vestigial traces all over your work. Once they have decided to haunt you, that is. These ectoplasmic moments litter your work for years. They are both the veil and the revelation, the thing that leads you to the cusp of the transformational.

I call these ectoplasmic moments avataric manifestations.

*

I am your unexpected You are the one who vanquishes my insides Each of us a separate war ??Unintended Worship,? Adonis

*

Abigail first appeared as Jasmine in a short story called ?Jazz Petals? that I wrote for an anthology edited by Kadija Sesay called ?Burning Words: Flaming Images Vol. 1.? Jasmine (called Jazz for short) was a young woman of color who came to her lesbian sexuality through playing the tenor saxophone. She comes out to her mother in a scene where she has colored her hair purple; in retrospect I now see mirrors: the scene in which Abigail comes out to her father, this time not sexually, but as a human being.

I didn’t know at the time that I was recovering the ectoplasmic traces that the ghosts of those two young women in the news had left on my psyche.

*

?A lustful touch cells swept away I exclude you from how-why-where and pursue my wonder ??Unintended Worship,? Adonis

*

When speaking to my poetry students, I refer to these ectoplasmic moments as ?the wet spot of the soul.? A necessary condition of melancholy and displacement that produces the poet’s ache to make the poem.

*

I remembered Khalil Gibran as I prepared to write, and his line?to know the pain of too much tenderness.

*

Amitav Ghosh, on a stage in Durban, South Africa, expressed this thought in response to a question: What is often most important to me when writing, even in a historical moment, what matters most, is not so much the particulars of that historical moment, but the texture of the characters’ lives.

This was the epiphany I had experienced in looking for the texture of Abigail’s life.

*

Ndi Idume, my father’s clan, says that while the chicken is a sensible and industrious bird, one that in its own way is indispensable, humble even in its being, that at some point in a man’s life, because he is a man, he should be an eagle.

*

and the earth too narrow for the earth. How should he read you, O woman/O city how should he read you? ??Unintended Worship,? Adonis

*

There was, I suppose, the desire to create a text where the writer’s life is evacuated; text where the writer’s body cannot be said to occupy it, in a real or imagined way.

I wanted a narrative where it would be hard to connect to it any emotional?and in some ways conceptual?framework that had not itself been generated by the narrative.

In a sense, when I say that I was seeking to create a text devoid of my own emotional interjections, not as textual topography, but as imaginative topography, I mean that I intend to ?translate? the experience of this character as closely as I can. But since the root of ?translate? in Latin really means to betray, then again, I ask you, how can you trust me? What I mean to say is, I won’t lie. I won’t.

But if I have lied, if I have in some way betrayed Abigail, I hope it is to you.

*

At the core of this book is a human being.

At the core of this book is the tragedy of sex trafficking.

Third-fastest-growing industry, after arms and drugs, is the trafficking of young women for sex.

You won’t find it listed on the GDP or GNP of any nation. Everyone pretends that it doesn’t happen.

In writing this book, I have tried to stay away from the quantitative, from the cumulative, from numbers, statistics, and all sure attritions to our attention and compassion. I have tried to remove any sentimentality and polemic.

This is the story of a human being.

In the end it doesn’t matter how many young women are victims of this trade.

One is already one too many.

*

Another anthology opportunity from Kadija came up: to be part of Penguin’s ?IC3,? a definitive collection of black British voices. I returned to the haunting, to the ectoplasm. This time it had a shape, a form, and a name: Abigail. I had 2,000 words and so I wrote what became the first full form of ?Becoming Abigail.? As a short story. As a poem.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but this idea, this story of a young girl forced into prostitution by her relatives in a foreign country who had brought her there under false pretenses, was only the dim outline of a form still barely glimpsed.

I still did not have the compassion for this voice, the words for this kind of tenderness, the courage for this kind of betrayal.

*

In ?The Duino Elegies,? Rilke said that terror is but the onset of a beauty we are yet to comprehend. He says it better.

*

So, here I am at the World Republic of Letters Lannan Symposium in Washington, D.C., trying to write this between panels and presentations and talks and readings. It strikes me as odd but appropriate that this book should again be connected to the Lannan’s.

Last night, I heard of a poet called Adonis for the first time. With embarrassment I admit this because one could argue that he is the foremost Arab poet, after Darwish. I am embarrassed because his words are so striking. Yet last night, in an improvisation that would have made Coltrane happy, he read with a Jamaican poet, Mark MacMorris. Mark read in English, Adonis in Arabic.

When Mark read from ?Unintended Worship,? I felt something happen, a gift from Abigail, and why not? If we must believe in ghosts, then we must also believe in their corporeality. The poem was Abigail, in so many ways, and I was glad I had not read Adonis or heard of him. I was glad because I can feel some ease knowing that what I translated came from my own ectoplasmic haunting and not from another’s.

It feels good to know that one has kin in this enterprise.

*

Some of us are the other’s sacrifice Each of us is the other’s worship ??Unintended Worship,? Adonis

*

When I went to Berlin finally, the wall had fallen. Yet there was still the notion of a conceptual wall, perhaps in this way more impenetrable because of its invisibility. The wall is a yellow line in the road. I stepped over it many times, ignoring the angry cars. On either side I was Chris. One either side I was not Chris.

This was Abigail.

*

Ben Okri wrote an exquisite novel at age 21 called ?Landscapes Within.? It changed me. It changed me to know someone so close to my age, someone publishing novels when I was, could write so well about the interior of another’s soul. It made me want to stop writing thrillers and write literary fiction. I did.

Ben rewrote that book 17 years later as ?Dangerous Love.? In the introduction he claimed that since Renaissance artists saw nothing wrong with revising their work as their skills improved, he saw no reason why he couldn’t do the same. Again Ben taught me something about the courage of being the kind of artist you want to be.

So. Two years after ?Becoming Abigail? was published as a short story in an anthology, I realized that while I had found the kernel of the narrative thrust, I had yet to find the texture of her life. I had yet to write ?Becoming Abigail.?

*

Then one night I saw a young Chicana woman read Neruda in Spanish, read: last night I wrote the saddest lines….

Then one night, two days after I arrived in Marfa, Texas, on a Lannan Foundation Residency, woken by the melancholic call of a train whistle, Abigail stepped out of the shadows of my mind.

It began with that train. I know, I know, those damn trains. It was 4 a.m., and displaced from sleeping on the couch, I began to write to Randy Crawford’s ?Rainy Night in Georgia,? and with it, as with Proust’s Madeline, came memories. One memory was of watching a film called ?Ashanti? in Nigeria in the ’80s. The film was about sex trafficking and starred Beverly Johnson, Omar Sharif and Peter Ustinov. There it was again, the ectoplasm, the residue of an old ghost.

And with this memory came all of the emotional memory of childhood. Of dusty savannahs sighing into the horizon with a loss there are no words for, no smells for. Of being teased as a sensitive child. Of watching that body hanging from an orange tree, hanging from the shame of something done in an unspeakable war. Of playing in burned-out tanks and in chapels that smelled of bat droppings. Of being invisible. Of carrying a core of melancholy so deep that none of the love lavished on me could melt it.

I was betraying Abigail fast and furious on the keyboard. Typing and typing and typing.

*

He listens to her body (her body is his language, with her body he speaks) ??Unintended Worship,? Adonis

*

This is how the transubstantiation began. Maybe this was what drew me to the church as a child, to the incense and candles, drew me into the priesthood as a young man and now, much older, draws me still toward the unspeakable, the ineffable. The unspeakable name of God is hidden in the human body. This is law.

And regardless of my attempts, my body is all over this book. My soul is interwoven with Abigail’s soul. My heart is her heart.

Three weeks later, I had the first draft done. Months later, the book.

*

I create?I create nothing but cracks and rifts? Is it why he says to the woman?the city I write in order to belong to you my face a meteor and you the space? ??Unintended Worship,? Adonis

*

When asked, I often say that I write to find my own humanity, that I am in a desperate battle to redeem myself, to make myself beautiful in the world. And yet in finding Abigail, I feel reluctant to claim my humanity, I feel undeserving. I feel awe in the face of her. She is the meteor and I, her space.

*

One of my readers, Eloise, a friend who teaches me about grace and beauty every day, said: ?It is as though you have a young girl inside of you.?

This is the best compliment I could have received. In a way, I am not sure I deserve it. But I take it. I take it.

*

. . . Hence there remains nothing for us but to love not knowing why ??Unintended Worship,? Adonis

*

This is how I came to Abigail. This is how I came to this becoming. There will be others. And no doubt I will return to this essay and flesh it out, shape it more, become more.

But for now I ask you, in all humility, to do something to save these young women. Come, buy this book, meet this extraordinary young woman who came through it, follow her in ?Becoming Abigail.?

Chris Abani Washington, D.C. / Los Angeles

The lines of poetry, reprinted here with permission, come from ?Unintended Worship,? from the book ?If Only the Sea Could Sleep: Love Poems by Adonis? (Green Integer 77, 2002).

Next Page: The full-text version of the first four chapters of “Becoming Abigail”Editor’s note: The following are the first four chapters of “Becoming Abigail” by Chris Abani (Akashic Books, 2006)

Chapter 1: Lay It As It Plays

And this.

Even this. This memory like all the others was a lie. Like the sound of someone ascending wooden stairs, which she couldn’t know because she had never heard it. Still it was as real as this one. A coffin sinking reluctantly into the open mouth of a grave, earth in clods collected around it in a pile like froth from the mouth of a mad dog. And women. Gathered in a cluster of black, like angry crows. Weeping. The sound was something she had heard only in her dreams and in these moments of memory?a keening, loud and sharp, but not brittle like the screeching of glass or the imagined sound of women crying. This was something entirely different. A deep lowing, a presence, dark and palpable, like a shadow emanating from the women, becoming a thing that circled the grave and the mourners in a predatory manner before rising up to the brightness of the sky and the sun, to be replaced by another momentarily.

Always in this memory she stood next to her father, a tall whip of blackness like an undecided but upright cobra. And he held her hand in his, another lie. He was silent, but tears ran down his face. It wasn’t the tears that bothered her. It was the way his body shuddered every few moments. Not a sob, it was more like his body was struggling to remember how to breathe, fighting the knowledge that most of him was riding in that coffin sinking into the soft dark loam.

But how could she be sure she remembered this correctly? He was her father and the coffin held all that was left of her mother, Abigail. This much she was sure of. However, judging by the way everyone spoke of Abigail, there was nothing of her in that dark iroko casket. But how do you remember an event you were not there for? Abigail had died in childbirth and she, Abigail, this Abigail, the daughter not the dead one, the mother, was a baby sleeping in the crook of some aunt’s arm completely unaware of the world.

She looked up. Her father stood in the doorway to the kitchen and the expression she saw on his face wasn’t a lie.

?Dad,? she said.

He stood in the doorframe. Light, from the outside security lights and wet from the rain, blew in. He swallowed and collected himself. She was doing the dishes buried up to her elbows in suds.

?Uh, carry on,? he said. Turning abruptly, he left.

The first time she saw that expression she’d been eight. He had been drinking, which he did sometimes when he was sad. Although that word, sad, seemed inadequate. And this sadness was the memory of Abigail overwhelming him. When he felt it rise, he would drink and play jazz.

It was late and she should have been in bed. Asleep. But the loud music woke her and drew her out into the living room. It was bright, the light sterile almost, the same fluorescent lighting used in hospitals. The furnishing was sparse. One armchair with wide wooden arms and leather seats and backrest, the leather fading and worn bald in some spots. A couple of beanbags scattered around a fraying rug, and a room divider sloping on one side; broken. Beyond the divider was the dining room. But here, in the living room, under the window that looked out onto a hill and the savanna sloping down it, stood the record player and the stack of records. Her father was in the middle of the room swaying along to ?The Girl From Ipanema,? clutching a photograph of Abigail to his chest. She walked in and took the photograph from his hands.

?Abigail,? he said. Over and over.

?It’s all right, Dad, it’s just the beer.?

?I’m not drunk.?

?Then it’s the jazz. You know it’s not good for you.?

But she knew this thing wasn’t the jazz, at least not the way he had told her about it on other countless drunken nights. That jazz, she imagined, was something you find down a dark alley taken as a shortcut, and brushing rain from your hair in the dimness of the club found there, you hear the singer crying just for you, while behind her a horn collects all the things she forgot to say, the brushes sweeping it all up against the skin of the drum. This thing with her father, however, was something else, Abigail suspected, something dead and rotting.

?Shhh, go to bed, Dad,? she said.

He turned and looked at her and she saw it and recognized what it was. She looked so much like her mother that when he saw her suddenly, she knew he wanted her to be Abigail. Now she realized that there was also something else: a patience, a longing. The way she imagined a devoted bonsai grower stood over a tree.

Chapter II: Now

She thought it might rain but so far it hadn’t and though a slight breeze ruffled the trees, it wasn’t cold. Even down here on the embankment, the night was as crisp and clear as a new banknote. She suddenly wished she had seen a London fog, the kind she had read about; a decent respectable fog that masked a fleeing Jack the Ripper or hid Moriarty from Sherlock’s chase. She stopped walking. She was here.

The sphinxes faced the wrong way, gazing inward contemplatively at Cleopatra’s Needle rather than outward, protectively, but Queen Victoria had ruled against the expense of correcting the mistake. The obelisk, an Egyptian souvenir, had been a gift from Mohammed Ali. She wasn’t sure who he was, but she was pretty sure he wasn’t the boxer. Abigail looked at the cold smiles of the sphinxes. Like them, she was amused at the ridiculous impotence of the phallus they stared at. A time capsule was buried beneath the stone tumescence containing, among other things, fashion photos of the most beautiful women of the nineteenth century.

She stood gazing out at the dark cold presence of the Thames. Breaking open a packet of cigarettes she fumbled clumsily to light one. She didn’t smoke. With her first drag she imagined she could see the ghosts of those who had also ended it here. At the Needle. Suddenly afraid she smothered a sob, choking on the harshness of the tobacco, eyes tearing. Like the loss of her virginity.

None of the men who had taken her in her short lifetime had seen her. That she wore bronze lipstick, or had a beautiful smile that was punctuated perfectly by dimples. That she plaited her hair herself, into tight cornrows. That her light complexion was a throwback from that time a Portuguese sailor had mistaken her great-grandmother’s cries.

None of them noticed the gentle shadow her breasts cast on her stomach as she reached on tiptoe for the relief of a stretch. Never explored the dip in her lower back where perspiration collected like gentle dew. They never weighed the heft of her breast the way she did, had, from the moment of her first bump. Sitting in her room, the darkness softened by a tired moon straining through dirty windows, she had rolled her growing breast between her palms like dough being shaped for a lover’s bread. This wasn’t an erotic exercise, though it became that, inevitably. At first it was a curiosity, a genuine wonder at the burgeoning of a self, a self that was still Abigail, yet still her. With the tip of a wax crayon she would write ?me,? over and over on the brown rise of them. And when she washed in the shower the next day, the color would bleed, but the wax left a sheen, the memory of night and her reclamation. But not the men in her life; they hadn’t really stopped long enough. She was a foreign country to them. One they wanted to pass through as quickly as possible. None of them knew she had cracked her left molar falling out of a mango tree like a common urchin. Or that in his fear for her safety and the shame of her tomboy nature, her father beat her. Nor did they know that since then, the lushness of mangoes stolen and eaten behind sacks of rice in the storeroom brought her a near sexual release.

But then neither had she really seen them. She tried to. Staring. Watching from the corner of her eye. Trying to piece them together. But they gave nothing, these men. They were experts at hiding themselves, the details of their lives. Even when they walked hand in hand with her in public, it was never the luxuriating of one person in the presence of an equal. No. They led her, pulled her behind their chest-thrust-forward-see-how-lucky-I-am-to-get-such-a-pretty-young-thing walk. They never undressed with her, or for her. There was always a furtive shame to their nudity, and a need to be done quickly, to hide it, theirs and hers, behind clothes again. And this thing that was shameful about them, they put on her, into her, made hers. They left her holding it, like the squish of a tree slug in the mouth, slimy and warm. Something you wanted to spit out and yet swallow at the same time. And though there had only been a few men, sometimes she felt like there had been whole hordes.

She had been ten when her first, fifteen-year-old cousin Edwin, swapped her cherry for a bag of sweets. The caramel and treacle was the full measure of his guilt. Then while stroking her hair tenderly, he whispered softly.

?I will kill you if you tell anyone.?

Chapter III: Then

And even light can become dirty, falling sluggish and parchment-yellow across a floor pitted by hope walked back and forth, the slap of slipper on concrete echoing the heat gritting its teeth on the tin roof, the sound sometimes like rain, other times like the cat-stretch of metal expanding and contracting.

And there was also the business of reading maps. Her favorite thing. The only things she read. Other than old Chinese poetry in translation. Fragments, memorized, came to her. Mostly from Emperor Wu of Han. Dripping melancholy and loss; she couldn’t get enough.

The poem: Autumn Wind

I am happy for a moment And then the old sorrow comes back I was young only a little while And now I am growing old

She was lying face down over a large map spread out on the living room floor, studying it intently. She ran her fingers meditatively over the spine of the Himalayas, while peering at the upside-down fish that was New Zealand. There was something in the way the Amazon basin curled up, all green and fresh like a new fern unfurling, that reminded her of a story she had read somewhere about a Chinese poet from a long time ago who tried to live his entire life as a poem.

He was famous for the beautiful landscapes he created in low wide-lipped terra-cotta pots?white sand flowing like a bleached sea floating over the loam holding it up, sweeping up to the miniature trees that would inspire the later Japanese bonsai, rocks lounging in the shade, and little pools with the littlest fish. At least that’s what she imagined. There were no pictures to go by, nothing but what her mind could conceive. But it was the story of how he made his tea that stayed with her. Came flooding back as her hands roamed over the smooth green of the map. She mentally went through the process, making a love of it, measured in objects.

An intricate box made from rice paper that allowed just the right amount of air through, held up by a copper handle; and inside, a shallow pot with a lotus in the center. Then at dusk, the freshest tips of green tea picked and wrapped in the petals of the rare blue lotus from Egypt. The box, hung from the rafters of his veranda, took in all that was night. Dawn: the box taken down; the wait for the lotus petals to unravel slowly with the sun; and a pot of hot water, brought to boil; the leaves, dropped in the pot of water; inhaled, the gentle aroma of green tea, suffused with the longing of lotus. She liked that. Was like that. Wrapping herself each night in anecdotes about Abigail. Collected until she was suffused with all parts of her. She rolled the map up and snapped an elastic band securely around it. Leaving it in a corner, she crossed a shaft of light from the shutters and cut a swathe through the motes, leaving the room to the silence and the dirty, lazy sunlight.

Chapter IV: Now

The cigarette burnt her finger as it smoked down to the filter. She threw it into the river. Following its glowing path, she imagined the hiss of its extinction as it hit the thick wet blackness. Sucking her finger she watched a train rumble across a bridge flickering light from its coaches into the water, back and forth over the Thames, carriages lighting the darkness of warehouses and tired stations. It was like the reassurance of blood. That life would go forwards and backwards, but never stop. Not unless the tracks were snowed over.

She pulled up her left sleeve and absently traced the healed welts of her burning. They had the nature of lines in a tree trunk: varied, different, telling. Her early attempts were thick but flat noodles burned into her skin by cashew sap. With time came finer lines, from needles, marking an improvement. But there were also the ugly whip marks of cigarette tips. Angry. Impatient. And the words: Not Abigail. My Abigail. Her Abigail? Ghosts. Death. Me. Me. Me. Not. Nobody. She stared at them.

This burning wasn’t immolation. Not combustion. But an exorcism. Cauterization. Permanence even. Before she began burning herself she collected anecdotes about her mother and wrote them down in red ink on bits of paper which she stuck on her skin, wearing them under her clothes; all day. Chaffing. Becoming. Becoming and chaffing, as though the friction from the paper would abrade any difference, smooth over any signs of the joining, until she became her mother and her mother her. But at night, in the shower, the paper would dissolve like a slow lie, the red ink, warm from the hot water, leaking into the drain like bloody tears. That was when she discovered the permanence of fire.

Fumbling about in her bag, she pulled out her purse. Opening it, she stroked the two photographs in the clear plastic pouch, the faces of the two men she loved. Her father, obsidian almost, scowling at the world. Derek, white, smiling as the sun wrinkled the corners of his eyes.

?I am sorry.?

She muttered the mantra repeatedly. Soothing.

It was getting chilly and she wished she was wearing more than a light denim shirt. No point in catching a cold as well, she thought, sniffling unconsciously.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.