‘Chaos & Caliphate’: Sanctions, Revolutions and Sectarian War

Excerpts from a new book chronicling a quarter-century of struggle in the Greater Middle East introduce us to a man who risks life and limb defusing land mines for a pittance, and to an idea about the best hope to stop the civil war in Syria. OR Books

OR Books

The following is an excerpt from Patrick Cockburn’s new book, “Chaos & Caliphate: Jihadis and the West in the Struggle for the Middle East,” from OR Books. It is a compilation of Cockburn’s coverage of the Greater Middle East from 1990 to the present day.

Iraq, Oct. 20, 1996

It is probably the most dangerous way to make a living in the world. “I do it because I would prefer to die than see the rest of my family starve,” says Sabir Saleh, a middle-aged man who used to be a farmer but is now too poor to hire a tractor to plough his land. Every morning he goes out into the minefields laid around Penjwin, a Kurdish village in northern Iraq shattered by fighting in the Iran–Iraq War. Saleh looks for one mine in particular: the Italian-made Valmara, one of the most lethal anti-personnel mines in existence. It is not easy to spot, because its five khaki-coloured prongs look like dried grass. Pressure on any one of them causes the Valmara to jump to waist height and explode, spraying 1,200 ball bearings over a range of 100 yards.

“I defuse the mine with a piece of wire,” says Saleh. “Then I unscrew the top of it and take out the aluminium around the explosives. When I have taken apart six mines I have enough aluminium to sell for 30 dinar [about 75 pence] to a shop in Penjwin.” After a day in the minefields he hopes to have recovered enough aluminium to feed his family of eight. “I make enough money to buy food for them, but not enough to buy clothes or anything else,” he says. He was a farmer before being drafted into the Iraqi Army for six years to fight the Iranians. To plough his land he would need to hire a tractor for £2.50 an hour, money he does not have. So, in the last few years, he has defused 2,000 Valmaras.

The mountain slopes around Penjwin are infested by mines. More than anywhere in the world it is mines that shape the lives of local people. Bahktiar Ali, an 18-year-old orphan, says his mother was killed in February last year when she trod on a mine while looking for firewood. Now he earns money guiding people illegally into Iran through the minefields.

Everybody in Penjwin knows somebody who has been killed by mines, and many point to their own injuries, mostly sustained when looking for Valmaras. “You can divide people in Penjwin into those who make their money from dismantling mines and selling the aluminium and those who don’t,” says Abdullah Ahmed, a local man who works for the Mines Advisory Group (MAG), a British-based charity which clears minefields. Over 2,000 Kurds are known to have been killed by mines since 1991, but the real figure is probably 50 per cent higher.

Most Valmaras are buried underground with only the prongs, one of which is usually connected to a trip wire, visible. “Defusing is very difficult,” says Selwar Hama Mustafa, who has now given up and works in a garage in Penjwin. “You have to get a wire into a hole, and then sometimes you can’t unscrew the top of the mine because it is rusty.” The Valmaras are usually surrounded by smaller anti-personnel mines. Abdullah Ali, his left leg ending in a stump, says: “I was looking for aluminium. I didn’t notice there was a little pressure mine under my foot.”

Even though the Iran–Iraq War ended in 1988, there is no danger of mines being in short supply. Polly Brennan of MAG says the Iraqi Army planted between 10 million and 20 million along the border with Iran, one for “every man, woman, child, chicken and donkey.” Hunting for mines may be a dangerous and not very profitable occupation but, apart from taking goods and people across the Iranian border, there is no other way of making a living. Sabir Saleh has started taking his children into the minefields to learn how to defuse a Valmara, “so they can earn a living, too.”

Syria, June 2, 2013

The best hope for an end to the killing in Syria is for the US and Russia to push both sides in the conflict to agree to a ceasefire in which each holds the territory it currently controls. In a civil war of such savagery, diplomacy with any ambition to determine who holds power in future will founder because both sides believe they can still win. Mutual hatred is too great for any long-term deal on sharing power. A ceasefire would have to be policed on the ground by a UN observer force. I recall the much-maligned UN Supervision Mission in Syria in 2012 arranging a ceasefire in the hardcore rebel town of Douma on the outskirts of Damascus. It did not stop all the shooting but many Syrians lived who would otherwise have died.

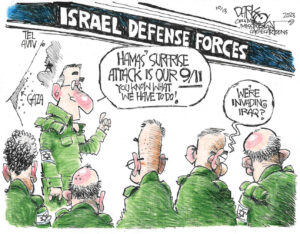

The White House has said in the past few days that its top priority in Syria is to impose regime change, but this is a recipe for a very long conflict. Why should Assad and his government surrender when they are more than holding their own on the battlefield? Moreover, Washington appears to have shut the door on the idea of Iran, a main player, attending the peace conference in Geneva. This again is unrealistic if the aim of negotiations is to end the fighting.

There may be a more sinister reason why the US has started setting the bar so high for talks. Washington’s involvement is greater than appears because so much of it goes through Qatar, with the CIA determining who gets arms and money sent via Turkey. This would also explain why Britain and France are so keen to send the rebels weapons.

The explanation for the actions of the Western states may be that they do not want the war to end except as a victory for their allies. This certainly is the view of many in the Middle East, such as Mowaffak al-Rubaie, the former Iraqi national security adviser, who says the civil war “is the best option for the West and Israel because it knocks out Syria as an opponent of their policies and keeps Iran busy. Hezbollah is preoccupied by Syria and not with Israel. Turkey’s idea of a new Ottoman empire is gone with the wind.” This is a cynical but probably correct explanation for why the US, Britain, France and the Sunni monarchies do not want the war to end until they can declare victory.

Patrick Cockburn is currently Middle East correspondent for the Independent and worked previously for the Financial Times. He has written four books on Iraq’s recent history—The Rise of Islamic State, Muqtada al-Sadr and the Fall of Iraq, The Occupation, and Saddam Hussein: An American Obsession (with Andrew Cockburn)—as well as a memoir, The Broken Boy and, with his son, a book on schizophrenia, Henry’s Demons, which was shortlisted for a Costa Award. He won the Martha Gellhorn Prize in 2005, the James Cameron Prize in 2006, the Orwell Prize for Journalism in 2009, the Foreign Commentator of the Year in 2013, and the Foreign Affairs Journalist of the Year in 2014.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.