Chain Linked

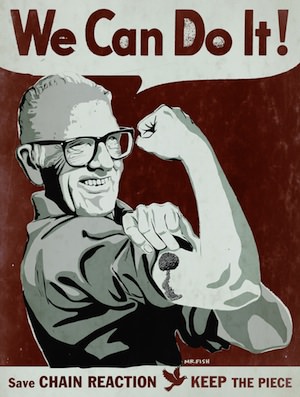

On Feb. 25 the Santa Monica City Council votes on whether Paul Conrad's peace sculpture should be knocked over and replaced with retail development. Because nothing says we should work to prevent nuclear self-annihilation like a Tommy Bahama, a food court and a lighted fountain full of pennies tossed by shoppers wishing for world peace with their eyes closed.Nothing says we should work to prevent nuclear self-annihilation like a Tommy Bahama, a food court and a fountain full of pennies tossed by shoppers wishing for world peace with their eyes closed.

In a time of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.

— George Orwell

In 1991, Woody Allen published an essay in Tikkun magazine titled “Random Reflections of a Second-Rate Mind.” In the piece he discussed, among other things, how the subjectivity of the God concept prevented morality from ever becoming anything more substantive than a matter of opinion, with one person’s idea of right and wrong, of truth and justice, being as relevant to our common ethics as an argument claiming the superiority of one favorite color over any other.

Allen also talked about how he preferred the gutsy temerity of the female characters written about in the Bible over the credulous obedience exhibited by their male counterparts. He claimed that anybody too demure or subservient to defy the sanctimonious bullying of a “vain and sadistic Holy Spirit” deserved zero respect and infinite ridicule for the sin of not listening to the existential distress, animalistic passion, irrepressible curiosity and glorious self-determination of their own heart.

So, Eve’s defiance of the Almighty’s dictatorial command that she relinquish her desire for free will and follow her mate’s lead and remain gleeful and clueless and fearful of knowledge itself, was described as one woman’s brave opposition to an entirely automated life. Lot’s wife’s reason for turning around to lay her eyes upon the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, though she was warned by the Lord that such a deed would reduce her to a pillar of salt, was explained as an act committed in protest of divinity’s crippling inhibitions and pious intolerance of sexual and intellectual abandon. When Job’s wife told her husband to “curse God and die” because she thought God’s method of testing Job’s faith — by knocking down their house and killing all their children and slaughtering all their livestock — was a bit excessive, she was being both sensible and heroic.

Inferred by Allen’s praise of these fictitious women cast in Scripture as unvirtuous reprobates is the suggestion that the most principled among us have gotten it all wrong and that we are likely doomed as a result of our utter confusion regarding how we should conduct our moral behavior in a way that isn’t self-negating or self-serving.

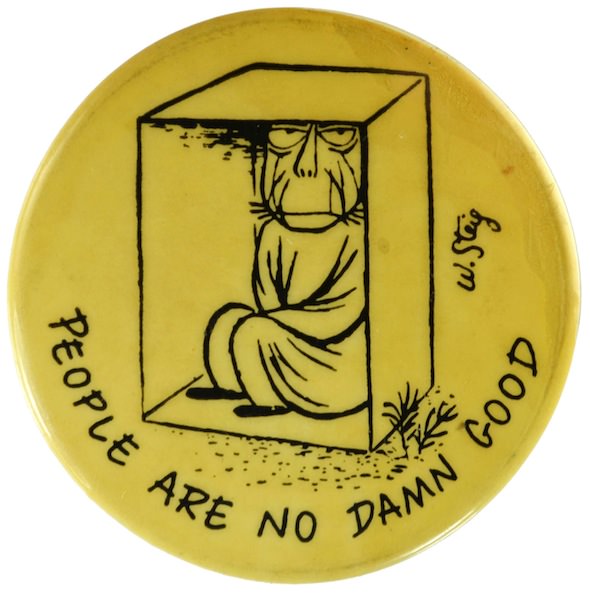

The author ends the essay by describing a pair of cufflinks that he received as a present when he was 15 bearing the famous William Steig cartoon depicting a glum sage in a box, the caption reading “People Are No Damn Good.” For Allen, the drawing, which was Steig’s very first (and famously rejected) submission to The New Yorker in 1930, was a useful and succinct life philosophy upon which we should all base our common understanding of the world — particularly when compared with the pandering nonsense that he saw being expressed by the likes of Will Rogers, who never met a man he didn’t like, and Anne Frank, who believed that all people were good at heart. Indeed, by assuming the worst in people, one need no longer be baffled by the persistent cruelties pingponging back and forth among individuals, cliques, clubs and nations since time immemorial. Rage, barbarism and contempt suddenly make sense, once it is accepted that people are no damn good, while random acts of compassion and kindness are relegated to the rarified list of infrequent happenings, becoming unique and praiseworthy and magical. Precious, even.

Of course, what makes the Steig cartoon truly fantastic is that it reflects a sentiment that, though deeply felt by everybody on the planet at one time or another, is seldom expressed out loud. In that way it is less a pronouncement of a freshly minted truth than a corroboration of a rather conspicuous reality that resonates with us because it substantiates what we already know to be true. In fact, a convincing argument could be made that the overwhelming majority of so-called truth-telling artists working as cartoonists, satirists, muralists and social realists are merely men and women willing to reveal what is already evident to everybody. In fact, an additional argument could be made that it is our attempt to codify our moral understanding of the universe into a supercilious philosophy of the intellect that detaches us from our ability to honestly connect with our surroundings. In other words, it is civility, much more than ignorance or blindness, that often deters us from boldly stating the obvious and recognizing reality without needing to wait for qualification from whatever social mores happen to be in vogue at the time.Consider, for example, the controversy in April 2004 sparked by the release of photographs depicting the flag-draped coffins of dead American soldiers being returned from Iraq and Afghanistan to Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. The majority of the released photos were attained through a Freedom of Information Act request by Russ Kick, a writer and First Amendment activist. Kick posted them on his website as a way to provide visual confirmation to everybody who already knew that the United States was engaged in a war using thousands and thousands of troops who were not the only fighters in the conflict considered to be armed and dangerous.

Remarkably, these images of U.S. casualties packaged and arranged in crisp, neat rows like so many boxes of ghoulish confections created a firestorm of protest from military families, conservative groups and pro-war patriots desperately attempting to beat back the unsettling notion that mass death wasn’t somehow glorious, awe-inspiring and worthwhile. It was as if knowing that dead servicemen and -women were being shipped in bulk to the largest military mortuary in the world was acceptable, but only as an abstract idea that could be recalibrated, spun, simplified into numbers and presented in such a way as to pose no significant threat to some narcissistic, though enormously common, desire to remain complacent and blissfully unaccountable for tragic circumstances.

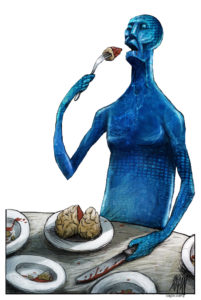

Similar attempts to present physical evidence to those crouching and squinting out at the world through the bunghole of plausible deniability would include the presentation of flammable drinking water and sacks full of dead fowl at congressional hearings convened to examine the dangers posed from natural gas drilling and fracking. There was also the forced parading of local German civilians through the liberated concentration camps and along the fetid rims of mass graves and around great heaps of rotting corpses at the end of the Second World War. The purpose of that exercise was to help those everyday members of the public who were complicit with Nazi rule better understand what the words mass extermination really meant and what sort of business was being conducted inside those giant factories down the road with the greasy smokestacks and the bulldozers. There was the Arnold Shapiro documentary from 1978 called “Scared Straight!” that endeavored to dissuade its target audience of snarky teens from becoming hardened criminals by having inmates berate juvenile delinquents on film by saying motherfucker and faggot and shit a whole lot and, more recently, with movies like “Food, Inc.” and “Meet Your Meat” revealing footage that exposed precisely how gruesome factory farming was both ethically and nutritionally.

Of course, these are all troubling examples of how willful ignorance of the sentiment expressed by the Steig cartoon can postpone any number of meaningful actions otherwise capable of preventing catastrophe from flourishing and how the demand for direct evidence to substantiate what we already know to be true runs counter to our desire to save ourselves from the peril of living in the present tense. Yes, injecting millions and millions of gallons of toxic chemicals into the ground will produce adverse effects to the environment and surrounding wildlife — we know that! Yes, rounding up millions and millions of people for the purpose of starving and slaughtering them will produce more than a few bones — WE KNOW THAT! Likewise, crime will often lead to jail and attempting to harvest living flesh like millions and millions of inert, pesticide-soaked soybeans for the purpose of increasing our profit margins will likely subvert our natural ability to express empathy for cows and pigs and chickens and our own physiologies.

What defect in our supposed higher intelligence insists that we continuously wait for proof before we acknowledge our acquiescence to bad behavior and the wanton destruction of people, places and things?

In Santa Monica there stands a landmark sculpture by three-time Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist Paul Conrad, one of the most ferociously conscientious and sincere political artists of the 20th century. The sculpture was erected in 1991 and depicts a 26-foot mushroom cloud that is composed of — what else? — chain links. For more than 22 years the clarity and precision of Conrad’s message warning against the doomsday scenario guaranteed by the proliferation of nuclear weaponry has given passers-by the opportunity to recognize the threat and to forgo humanity’s demand for corroborating proof from the real thing. But, of course, isn’t that the responsibility of the editorial cartoonist, even when he is a sculptor — to present the insane mathematics offered up by the bogus logic of nefarious men, women and institutions and portray the terrible conclusions assured by public apathy? If so, it might be wise to reconsider the intent behind the Steig cartoon insisting that People Are No Damn Good and interpret it more as an alterable prediction than an incontrovertible fact.

On Feb. 25 the Santa Monica City Council votes on whether the Conrad sculpture should be knocked over and replaced with retail development. Because nothing says we should work to prevent nuclear self-annihilation like a Tommy Bahama, a food court and a lighted fountain full of pennies tossed by shoppers wishing for world peace with their eyes closed.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.