Cartoon Protests Stoked by Dictators

Don't believe the hype about homespun religious anger: Middle Eastern leaders stoke religious riots because it makes their secular governments look tame in comparison.

Update: Cilck here for a Truthdig primer on who has, and who hasn’t re-published the controversial cartoons

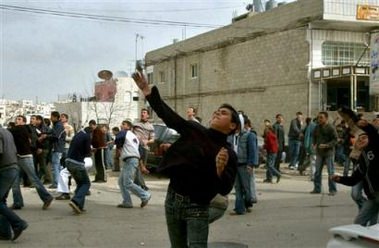

Many Western media organizations have portrayed the recent wave of riots and protests surrounding the publication of cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad as some kind of spontaneous, instinctual war cry among aggrieved Muslims. But when you take a closer look at the social and political contexts of these collective expressions of rage, certain patterns emerge that suggest a more manufactured phenomenon.

Syria is a perfect example, and the one that I know best, having spent the past year living and studying there. This is a country where absolutely nothing happens in public without the express authorization of the government. That’s what makes life in Syria both incredibly safe — it has one of the lowest crime rates in the Middle East and almost no domestic terrorism problems — and incredibly oppressive. Any time there’s a “demonstration” or a “rally,” or even a picnic involving more than one person, the government bureaucracy has to sign off on it.

So how was a gang of youths able to congregate on one of the premier avenues of the capital, destroy the Danish and Norwegian embassies and trash several other Western-owned buildings in the course of a long day? Damascus is a remarkably well-policed city, with government security drones (Mukhabarat) stationed on nearly every street corner, automatic rifles slung across their shoulders. These guards especially cluster around foreign embassies and the fashionable Abu Roumaneh district, where most of the destruction occurred; yet no clashes between protesters and guards have been reported.

We are left with two possible explanations: either all of Damascus’ top-priority guard posts were abandoned at the same time — all of the Mukhabarat stepped out for a daylong cigarette break — or the guards were complicit in the demonstrations-turned-riots. In light of the Asad regime’s proven readiness to defy the international community in the most blunt fashion, one could further presume that Syria’s security agents were not only complicit in this violence but actually helped coordinate it, focus it and contain it from behind the scenes to achieve some higher policy goal. Apparently the U.S. State Department has come to the same conclusion.

What policy goal might President Bashar Asad be pursuing by stoking a riot inside his own capital? Why would government henchmen work to cultivate a reputation for Syria as a nation on the brink of barbarity? For the very cynical reason that it makes the stable, secular Baath regime seem like the only bulwark against a restless religious population. The constant, muted oppression of Asad’s police state seems tame in comparison to the raw, explosive rage of the Muslim masses.

It’s an old trick, used by many of the most brutal regimes in the region: “Don’t depose us,” they say, “because look at how crazy our Islamist replacements are.” This argument has been put forward again and again by Arab and Muslim autocrats and seconded by our own Western governments, and up until Hamas’ landslide victory in the recent Palestinian parliamentary elections it had been a very effective way of shutting Islamist voices out of the debate.

The rationale behind Syria’s sanctioning of the Islamic riots in Damascus also explains Palestinian Authority leaders’ refusal to form a coalition government with Hamas. If you put your Islamic radicals up front where everyone can see them, goes the logic, then when they inevitably do something stupid the world will acknowledge how much better your corrupt, impotent but secular regime really is.

The spreading of the riots across the mountains to Beirut, which led to the same kind of targeted destruction of Western embassies, was probably engineered by the same government forces that allowed the “protest demonstrations” in Syria. Despite the withdrawal of Syria’s military from Lebanon last year, it is an open secret that Syrian security forces and intelligence networks still operate freely on the ground throughout Lebanon, and still wield considerable power over internal Lebanese affairs. Lebanon, like Syria, is a nation that is tightly controlled in terms of most kinds of public expression. The massive marches and protests that took place after the slaying of Rafik Hariri, for example, while often described in the news as “spontaneous” outpourings of sentiment and sure signs that the reform movement was at last standing on its own feet, were in fact a highly managed campaign authorized and funded by political elites.

The recent riots in Beirut are no exception. They undoubtedly required some measure of authorization, if not material support, in order to effectively mobilize in tandem with the riots in Damascus. It is doubtful that any of the existing Lebanese parties, with the possible exception of (Syria-allied) Hezbollah, would facilitate these kinds of demonstrations–which inherently threaten the delicate sectarian balance that has prevailed since the county emerged from its 15-year civil war. Again, only one party comes to mind that would (a) benefit from destabilizing Lebanon, (b) seek to blame it on radical Muslims and (c) have the operational and logistical resources necessary to carry out such an effective mass demonstration on short notice. The Lebanese interior minister himself blamed a core of “infiltrators” for stirring up the riots — an obvious reference to Lebanon’s meddling eastern neighbor.

A final piece of this (too) well-orchestrated series of demonstrations and riots is the role of Saudi Arabia. A Saudi blogger (“The Religious Policeman”) reported on Jan. 27 — before the spread of violence — that the Saudi government’s recently instituted boycott of Danish and Norwegian goods and media campaign against the two nations had come curiously on the heels of a crisis that the Saudi government desperately needed a way out of. Saudi Arabia was under fire from Muslims around the world for its very public mismanagement of the annual hajj pilgrimage, in which 350 pilgrims from mostly poor nations were trampled to death. This incident was huge news — front page in all the Arab papers for several days — and all blame was being put on the Saudi government because an almost identical tragedy (with a slightly lower death toll) had occurred in 2004 and the Saudis afterward had taken none of the promised preventive measures.

In a transparent attempt to divert domestic and international attention away from its second massively fatal mismanagement of Islamic affairs in two years, the Saudi government seized on a then relatively unremarkable piece of news about a controversy surrounding the reprinting of several cartoons insulting the Prophet Muhammad. Virtually overnight, according to “The Religious Policeman,” there were “simultaneous Saudi Government statements, Saudi newspaper articles, and sermons in all Saudi mosques, suddenly appearing four months after the original cartoons were published.”

Daily Kos wrote:

[The Saudi government’s] plan was to go on a major offensive against the Danish cartoons. The 350 pilgrims were killed on January 12 and soon after, Saudi newspapers (which are all controlled by the state) began running up to 4 articles per day condemning the Danish cartoons. The Saudi government asked for a formal apology from Denmark. When that was not forthcoming, they began calling for world-wide protests. After two weeks of this, the Libyans decided to close their embassy in Denmark. Then there was an attack on the Danish embassy in Indonesia. And that was followed by attacks on the embassies in Syria and then Lebanon.

In the Middle East, context is everything. Thousands upon thousands of Muslims do not one day wake up, see several cartoons and then become so enraged at the cartoons’ content that they organize themselves into torch-bearing, authority-evading, sign-waving mobs. Just as among Christians, Jews, atheists and people of every other persuasion, collective acts of violence among Muslims require prodding, and usually some form of outside management. It takes irresponsible guidance and a lot of material support to translate raw emotions into destructive activism, especially in countries as tightly regulated as those of the Muslim world today.

This is not in any way to absolve or defend the criminals who participated in these acts of destruction and chose to interpret their faith in a manner so inconsistent with the vast majority of their community. Rather, a fuller understanding of the social and political context in which the most violent of these “demonstrations” occurred indicates that we ought not to be so quick to condemn the overt perpetrators of these acts that we leave the pushers, the enablers and the demagogues off the hook.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.